Private landowners concerned about the risks of fracking may be able to prevent mining for oil and natural gas on their land – in perpetuity – without government regulation, according to a new analysis by Rob Jackson, professor of Earth system science at Stanford University, and his colleagues.

Rural Pennsylvania is one of many parts of the United States in which oil and gas mining activity occur. (Image credit: Rob Jackson)

Jackson and a team of legal scholars have assessed how an established legal agreement – the conservation easement – could enable individual landowners to restrict fracking on their property. They’ve dubbed this new approach a mineral estate conservation easement (MECE).

Fracking (as hydraulic fracturing is commonly known) has dramatically increased in the United States and now accounts for about half of all U.S. oil output. Despite this growth, many communities remain concerned about public health and safety.

As some local governments try to ban fracking, legal battles have yielded mixed success, largely because state governments are considered the greater authority on regulating oil and gas development. In Denton, Texas, voters approved a fracking ban only to have it overturned by the state legislature months later.

“People concerned about groundwater contamination and other potential impacts of fracking may welcome a new option for permanent conservation,” said Jackson. “The MECE is a conservation easement underground that provides landowners with legal flexibility to restrict hydraulic fracturing and other subsurface activities on their land in perpetuity.” The analysis is published this week in Environmental Law Reporter. (Click here for link to PDF.)

Nonregulatory action

A conservation easement is a contract (usually between a landowner and a land trust) whereby a landowner voluntarily agrees to sell or donate the right to use a piece of property in a certain way, commonly agreeing not to develop it. The restriction on the property often diminishes its value and the law allows landowners donating a conservation easement to take a tax write-off of the difference in fair market value of the land before and after the easement. Donors with larger tax bills could see significant savings without being required to give up private ownership of their property.

Conservation easements are popular in the America—over 100,000 easements cover 40 million acres of U.S. territory—and can be an attractive option for landowners.

“Around the country, individuals and communities have expressed growing concerns over fracking’s impacts on water quality, air pollution, and truck traffic. To date, though, there has been little meaningful action they could take,” said James Salzman, professor of law at UCLA and a co-author of the study.

The MECE could restrict mineral extraction under property, which could help landowners concerned about horizontal drilling and other activities. It gives people who own only the mineral rights on a property a new choice for setting aside those rights. The MECE would also allow landowners who own both the aboveground and belowground parts of their land to conserve what’s underneath the property while retaining the right to develop on the surface with houses or other structures.

“As conservationists worry about lack of environmental protection measures under the new administration, they will look to private law mechanisms to pick up the slack,” said Jessica Owley, professor of law at the Buffalo School of Law and co-author of the study. “Our work is proposing a new twist on an old idea that will facilitate protection of land.”

Existing language

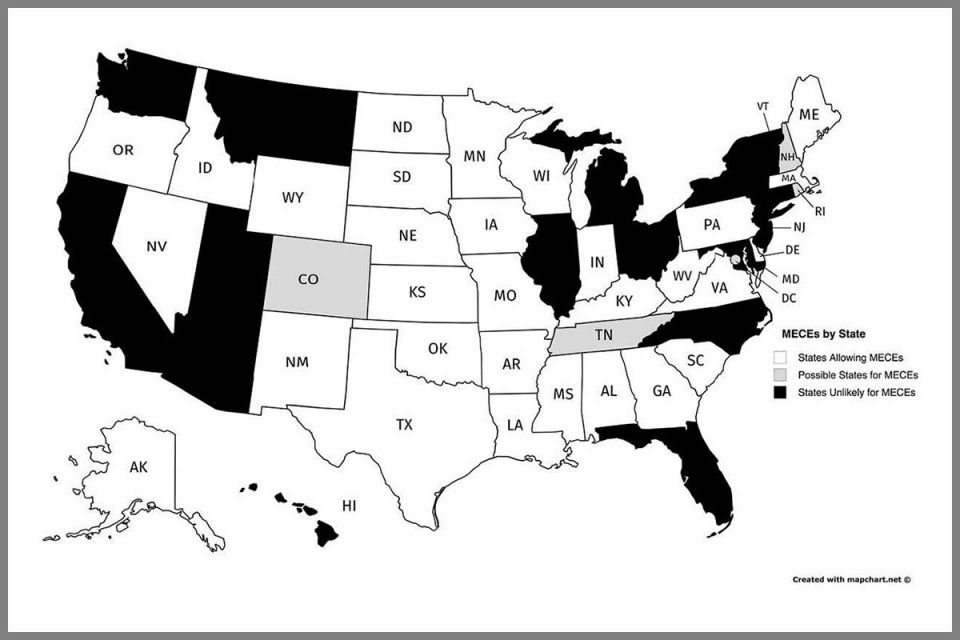

The researchers found that many oil- and gas-producing states, such as Alaska, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Wyoming, already have statutory language that could support the formation of MECEs.

For states where MECEs might not be legally supported, the analysis proposes amendments to state laws and the Internal Revenue Code that would allow MECEs to reach parity with the current use of conservation easements and be eligible for tax deductions.

“This is about consumer choice,” Jackson said. “The MECE could be a widely used tool for limiting hydraulic fracturing on property where desired.”

Rob Jackson is the Michelle and Kevin Douglas Provostial Professor and chair of the Department of Earth System Science. He is a senior fellow with the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment and the Precourt Institute for Energy.

Media Contacts

Rob Jackson, School of Earth, Energy and Environmental Sciences: (650) 497-5841, rob.jackson@stanford.edu

Devon Ryan, Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment: (650) 497-0444, devonr@stanford.edu