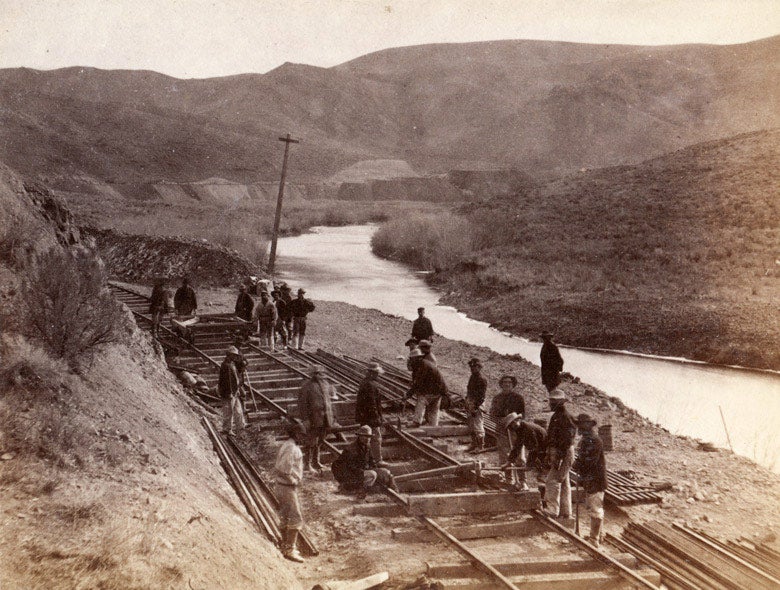

Chinese workers help lay tracks along the Ten Mile Canyon stretch of the Transcontinental Railroad route. Stanford professors Gordon Chang and Shelley Fisher Fishkin are leading an exploration of their lives and experiences. (Image credit: Courtesy Alfred A. Hart Photograph Collection, Stanford University)

Built in the mid-1800s, the Transcontinental Railroad was among the most ambitious enterprises of American engineering – as well as an important source of Leland Stanford’s wealth. Well over 10,000 Chinese laborers performed the grueling and dangerous work of tunneling through the granite of the Sierra Nevada. They were paid less than fellow Caucasian workers, and had fewer legal rights.

Scholars have long known that the Chinese were integral to the construction process, but they knew relatively little about who these workers were, where they came from, what they experienced and what they did after the railroad was completed.

Over the past three years a team of Stanford professors has been working to change that through the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project.

Led by Stanford history Professor Gordon Chang and Stanford English Professor Shelley Fisher Fishkin, the project is undertaking the most exhaustive search for materials related to the Chinese railroad workers ever conducted.

More than 150 scholars from around the world, from disciplines including history, American studies, literature, archaeology, anthropology and architecture, are working with Fishkin and Chang to help aggregate, assemble and analyze disparate sources of information.

The organizers are also partnering with the Chinese Historical Society of America (CHSA) to collect oral histories from descendants of the workers.

More than 50 of these workers’ descendants attended a recent event at Stanford, where scholars shared the status of the various facets of the project with the public

Speaking at the event, Luo Linquan, China’s consul general in San Francisco, said the Chinese railroad workers had helped reshape the geographic and social landscape of the West. Through this project, he said, their contributions “will be remembered by more and more people, both here in the U.S. and in China.” Chang noted that the project has received considerable attention in China, where the railroad workers’ experience is seen as an important episode in early America-China relations.

Richard Saller, dean of the School of Humanities & Sciences, told the audience that the gathering marked the first time that Stanford formally honored the memory of the Chinese who worked on the railroad. The project was “created in recognition of the crucial role that the Chinese who built the Central Pacific Railroad played in creating the fortune with which Leland Stanford founded our university,” Saller said.

Fishkin noted that when the researchers began the project they weren’t confident about finding more than a handful of descendants. But with outreach support from the CHSA, nearly 30 descendants have been identified and interviewed for the oral history aspect of the project.

In an effort to connect with even more descendants, Fishkin and Chang developed an online survey for the families of railroad workers, Chinese Railroad Workers in North America – Descendants Questionnaire, which may be completed in English or Chinese.

The Chinese railroad workers received no acknowledgment at the official celebration of the 100th anniversary of the completion of the railroad in 1969. Fishkin and Chang hope their efforts will ensure that doesn’t happen again in 2019, when the railroad celebrates its 150th anniversary.

Making connections

Working with support from the project, experts from North American and Asian institutions have recovered and shared materials such as photographs, payroll records and contemporary newspaper articles. In addition, more than 90 archaeologists are pooling their efforts and findings as part of an affiliated archaeology network.

One of the initial goals of the transnational project was to bring together researchers doing related work “literally into one room, and ask ‘what did we learn so far? what do we know? how can we work better together?'” said Barbara Voss, director of the archaeology network and an associate professor of anthropology.

“Thanks to better data gathering and improved communication among scholars, we’re starting to see the bigger picture,” Voss said.

Articles by many of the participating archaeologists were published in a recent edition of the journal Historical Archaeology, which dedicated an entire issue to the archaeology of the Chinese railroad workers in North America. The articles came out of a conference at Stanford that the project sponsored in 2013 that brought the archaeologists together.

As Voss put it, the archaeological evidence reveals that there was “not just one Chinese worker experience,” because some lived in large, permanent work camps for years at a time while others lived a nomadic lifestyle, moving to a new campsite every few days.

Some objects have been found in areas near railroads, where it is believed that Chinese workers camped temporarily during the railroad construction. “Though originally these discoveries were accidental,” Voss said, further archaeological examination demonstrated that these objects had indeed belonged to Chinese workers.

With regard to the recovery of additional items, Voss pointed out that archaeologists affiliated with the project are currently conducting surveys of previously unstudied segments of the first transcontinental railroad, in California and Utah, as well as surveys and excavations of Chinese work camps on other historic railroad lines. The researchers are optimistic that more items will be discovered as these research projects continue.

In addition to promoting scholarship on the topic through conferences and publications, Fishkin and Chang plan to make many of the source materials accessible to the public in an online, multilingual, digital archive.

Professor Jinhua (Selia) Tan from Wuyi University, a research collaborator in the Stanford Chinese Railroad Workers project, helped to create the Cang Dong Education Center in Guangdong Province to preserve and interpret the architectural landscape, as well as the culture and history of the villages from which many of the railroad workers came.

Stanford undergraduates are helping to tell the story, too. Under the direction of Chang and Fishkin, juniors Eve Simister and Noelle Herring curated an exhibit about the experiences of Chinese workers that is currently on display in the lobby of Stanford’s East Asia Library and will remain up until the start of the fall quarter. More than a dozen undergraduates have worked with the project as research interns, constructing annotated bibliographies and mining archival sources.

Quest for clues

The project’s research has uncovered thousands of photographs and historical documents in numerous archives and museums, including the California State Railroad Museum, the Bancroft Library, the Huntington Library, the Leland Stanford papers in the Stanford Library, the Library of Congress and the National Archives.

Despite intensive worldwide search efforts so far, the researchers haven’t yet come across text about the railroad experience written by one of the Chinese workers.

Letters from the workers that were sent back to China may have been destroyed during periods of war and social unrest during the 19th and 20th centuries, Chang said, or they may still be sitting in a long-undisturbed box in someone’s home waiting to be discovered.

Further, said Fishkin, historical societies in the American West wouldn’t necessarily have recognized the significance of documents written in Chinese and probably discarded them.

In their quest for clues, Fishkin and Chang examined payroll records from the Central Pacific Railroad Co., which are archived at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento.

They found that most of the time, the documents included information about the American contractors or Chinese “head men” in charge of work groups, but the names of the Chinese workers were missing. “On few occasions were Chinese workers hired directly, and even in these cases they were not given a proper Chinese name, making it very difficult to track down the actual workers,” Chang said.

Ultimately, all found materials will be entered into a custom-built archiving platform that Stanford Libraries constructed with a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, called Bibliopedia.

Scholars from North America and Asia will convene at Stanford in April 2016 to report on their findings for the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project. Research work will be published in a collection of essays and a preliminary version of the digital archive is expected to launch then. Together, these efforts, Fishkin said, will “provide a much richer picture than we ever had before.”

Media Contacts

Corrie Goldman, director of humanities communication: (650) 724-8156, corrieg@stanford.edu