Stanford lecturer reflects on a 90-mile trek across the Sierra Nevada

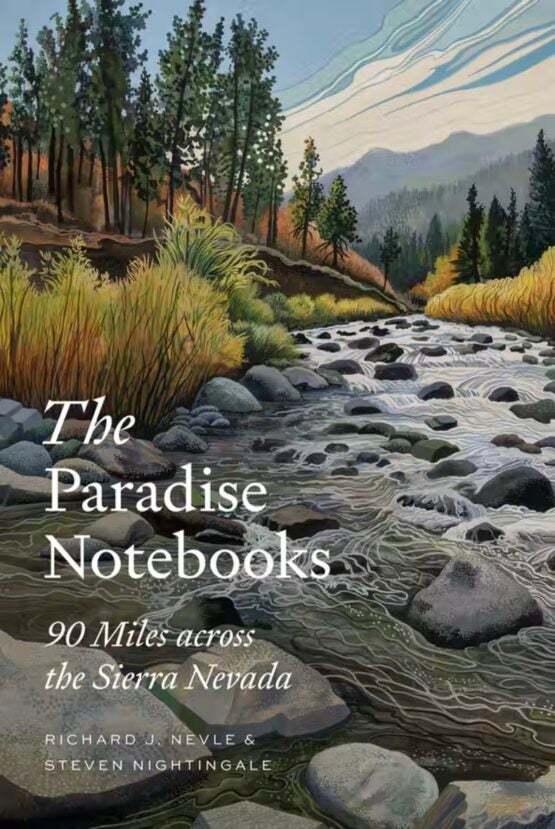

Richard Nevle, deputy director of Stanford’s Earth Systems Program, discusses his forthcoming collection of essays about the Sierra Nevada mountain range, The Paradise Notebooks.

In a forthcoming collection of 21 pairs of essays inspired by a 90-mile trek across the Sierra Nevada mountain range, Earth Systems Deputy Director Richard Nevle writes, “Walking in the high country of the Sierra Nevada, I see it is broken everywhere.”

The line refers to crumbling rocks fractured by ice “like a beer bottle left too long in the freezer.” But the sense of breakage extends beyond the granite in Nevle’s loving meditations on the grandeur and minutiae of the range, which he put into writing between the summers of 2017 and 2020 when wildfires torched nearly a million acres in the Sierra.

While he finds much to savor – the “bewildering joy” of mountain thunderstorms, the uplifting banter of chickadees, the “kinesthetic genius” of bighorn sheep, the wiliness of flowers – he also describes endless miles of conifers killed by drought, beetles that burrow into trees too dry to muster sap for protection, and lichens bathed in wind-blown pesticides. He wonders if a frog-killing fungal pathogen might have arrived in remote alpine lakes by way of trout hatcheries, “and from there into the holds of aircraft used to bomb the Sierra’s lakes with fry.”

Nevle’s essays in The Paradise Notebooks (Cornell University Press) alternate with reflections and poems by his friend and backpacking companion, poet Steven Nightingale, BA ’73. Interspersed throughout the 175-page collection are illustrations by Mattias Lanas, MS ’12, and passages from sources ranging from Emily Dickinson and Shakespeare to a pamphlet on ground squirrel management in California.

In the conversation that follows, Nevle discusses his reckoning with hope and grief in the face of environmental destruction and his book, released April 15. He shares why he keeps returning to the Sierra Nevada backcountry, and how he moved forward from despair when it seemed “the science wasn’t getting through.”

Why did you want to write this book?

I met the Sierra Nevada when I first came to California for graduate school at Stanford in the late 1980s, and I’ve gone there every year since. My wife and I have taken our daughter to the mountains since she was an infant. And I’ve shared some of my favorite places in the Sierra with students in a field course I teach.

Three members of Nevle’s 2017 backpacking party – Deborah Levoy, Steven Nightingale, and Lucy Blake (left to right) – walk the last steps to New Army Pass. Mount Langley looms in the background. (Image credit: Richard J. Nevle)

The time I’ve spent in the mountains has filled me with such wonder, curiosity, and respite, and I wanted to be able to share these gifts with people, including those among my own extended family and many others who don’t have access to wild places like the Sierra Nevada. I wanted to try to use language to create the feeling of being there.

I’ve always been drawn to natural history as a way of connecting to places, and I’ve learned that places can become even more special to us as we learn to see them from multiple perspectives, not just scientific ones. Steven and I walked with our families for thirteen days across the Sierra Nevada, and that was when we began to dream up the idea for a book that would bring a whole-minded, learned, loving attention to place.

Although the solace I’ve found in the Sierra Nevada has been threatened by fires and by droughts, it’s still a place where I return – partly because of the way it invites my curiosity, and partly because it gives me a reserve of strength I need to work with students and help foster their growth as environmental scholars and leaders. Being in the Sierra has also helped me more deeply appreciate the wildlife that exists in urbanized settings, including Stanford’s campus and where I live in downtown San José.

To what extent does your writing connect with your teaching here at Stanford?

Teaching informed the book in many ways, particularly a class I have taught since 2013 (EARTH193). The class is built around creating a field journal in which drawing and close observation foster attentiveness and curiosity that leads to scientific questions.

In fact, the book’s illustrator, Mattias Lanas, is an Earth systems alum who has helped to teach that class. He’s a naturalist and scientific illustrator who helps students learn how to use pen and ink and watercolor to document their observations.

The class covers a range of natural history subjects from climate science to geology to ecology. This book is a bit of a reflection of that class in that it covers many different aspects of the Earth and environmental sciences manifested in the Sierra and a healthy dose of poetry.

The book is also deeply informed by my work teaching EARTHSYS 149: Wild Writing with Emily Polk. One of our claims in Wild Writing is that the environmental essay can be a form of advocacy.

How was your process influenced by what was happening in the world as you wrote?

Like a lot of people during the pandemic, I started to appreciate the natural world in my immediate environment even more, sometimes literally in my backyard. I saw several species of warblers for the first time in the trees surrounding my backyard. They were migrating through, maybe on their way to the Sierra.

The 90-mile hike across the Sierra Nevada that inspired The Paradise Notebooks included an ascent to the summit of Mount Whitney. (Image credit: Shutterstock)

If anything, COVID made me feel an even deeper kinship with the suffering of the natural world.

I couldn’t help but see a connection between the COVID pandemic, which threatens human life, and chytrid, a disease that’s caused so many species of amphibians to become extinct across the globe.

The increasing extent in severity and intensity of wildfires we’ve seen in the West in the past few years figured into my writing even more than the pandemic. During 2018, wildfires in the fall made it smoky on campus for weeks. I thought a lot about the fact that I was breathing particles of immolated trees and animals from the Sierra Nevada.

During the summer of 2020, when fires were burning throughout the West, I again thought about what was in the ash and what was being destroyed. And of course, everyone who was in the Bay Area in September 2020 remembers that day of apocalyptic orange skies. A lot of the loss from wildfire in California is climate driven, and so I think the fires have felt like symptoms of a parallel disease affecting us – like the world and our species are profoundly ill.

Which authors and experiences have influenced your writing?

I can’t escape the influence of John Muir. When I first encountered his writing in my 30s, I felt admiration for his capacity to use language to convey a spiritual experience of the natural world, and awe at his powers of observation. And yet, there are disturbing passages in Muir’s writing where you realize his magnanimity didn’t extend to the indigenous people he encountered in the Sierra Nevada. I’m still wrestling with how to hold the complexity of Muir as a person, even as I feel gratitude for what I’ve been able to learn from his writing.

Annie Dillard is another huge inspiration. The natural world she describes is illuminated with beauty and wonder, but is also haunted by violence and suffering. I admire how her writing bears witness to this complexity. Terry Tempest Williams’ writing has inspired my efforts to celebrate place and look for beauty in the natural world, even while grieving what’s being lost. And Craig Childs: When I first stumbled across one of his books, House of Rain, it was like being struck by lightning.

As far as personal experiences, the 2008 Deepwater Horizon spill was a real moment of reckoning for me. I felt such a deep and personal loss because I have a strong bond to the Gulf Coast. I grew up in Houston, and as a kid, my family would go fishing and crabbing all along the Texas coastline. My dad would harvest oysters by wading out on the reefs at low tide, shuck them on a peer, and plop them straight into me and my brothers’ waiting mouths. We could spend a week on Galveston Island and basically live off the land and sea. I saw the spill affect so many people whose livelihoods depend on the biological productivity of the Gulf of Mexico. And I felt the science about what we’re doing to our planet just wasn’t getting through.

Over time, I concluded that the despair I felt over the environmental destruction was a spiritual dead-end. Blind hope can be equally useless. What I realized is that I had to keep working to make a difference in whatever way I could.

Martin Luther King Jr. spoke about the importance of taking a first step without being able to see the top of the staircase. Rebecca Solnit has written about this idea, too – namely, the importance of continuing with aspirational work even though you can’t see the outcome. We have to work like it matters through being intentional, living ethically, and using evidence and science to help inform our actions and decisions.