Stanford professors examine higher education against innovative Bay Area landscape in new book

Stanford professors Dick Scott and Mike Kirst analyzed 45 years of higher education data in the Bay Area. Their findings showed that higher education has fallen behind the needs of an ever-changing region.

The San Francisco Bay Area, notably Silicon Valley, is known for its ingenuity and rapid growth, thanks in part to the global technology companies that reside there.

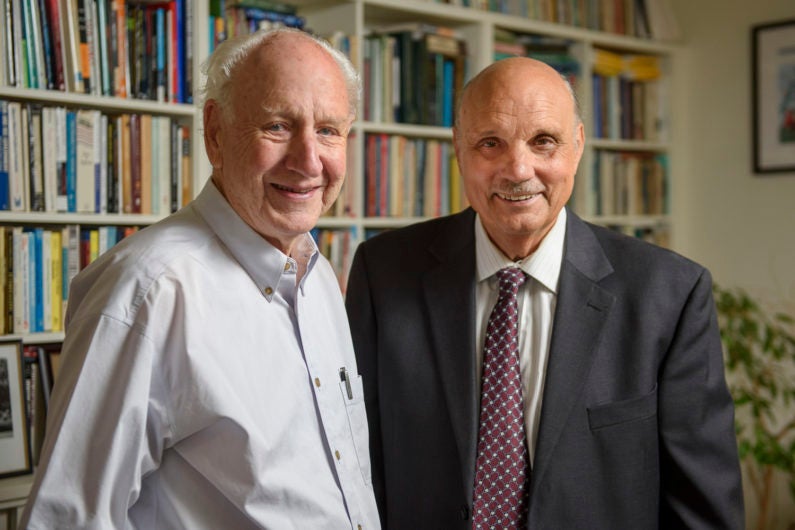

Stanford professors emeriti Dick Scott, left, and Mike Kirst examined higher education

in the San Francisco Bay Area and found a mismatch between the educational system and Silicon Valley’s needs. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

An important industry that Silicon Valley depends on is higher education, but it appears that this relationship is an uneasy one, according to Dick Scott and Mike Kirst, two emeriti Stanford faculty members. They, together with a team of colleagues associated with the John W. Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities, have completed a longitudinal study describing developments in this area over the past 45 years (1970 to 2015).

In their new book, Higher Education and Silicon Valley: Connected but Conflicted, they detail the struggles of the Bay Area’s post-secondary educational institutions against the landscape of the region’s thriving and ever-changing economy. The research covers more than 350 postsecondary organizations in the Bay Area, including traditional degree-granting colleges and universities, community colleges and privately run vocational and professional schools.

Stanford News Service spoke to Kirst and Scott about their new book.

Why is there a “mismatch” between higher education and the Bay Area?

Scott: While the two “fields” – higher education and Silicon Valley firms – share important values, including a keen interest in developing and using knowledge and a reliance on networks of professionals and specialists, they are mismatched in many ways. The two fields developed under different conditions, operate under different pressures and often serve different missions, so it is not surprising that they differ substantially in their values, norms and pace of change. In colleges – particularly degree programs – the pace of change has been relatively leisurely. In contrast, Silicon Valley has renewed itself multiple times in recent decades.

Kirst: At the policy level, we’re operating under a master plan for higher education that was approved in 1960 and has never been overhauled in a major way since then. For example, the master plan didn’t anticipate an economy that needed so much rapid reskilling of adults – many of whom have a solid education. The regional economy changes at an exponential rate whereas the higher education sector experiences at best incremental change.

What challenges does this “mismatch” create for the area?

Scott: Today, there is a real divergence between the needs of the Valley and the capacity of the system. The numbers of high school graduates eligible for the University of California or state colleges have increased through this period but the supply of student slots has barely moved, to the point where almost half cannot be accommodated. The only serious growth in the public system has been with community colleges, which now enroll more than half of all students.

Kirst: The Bay Area hosts only three state colleges today – just as in 1960 – although the population of the region has increased from 4.6 million in 1970 to more than 7 million.

But, even community colleges are struggling, right?

Scott: Yes, they are also badly underfunded. They’re trying to do this dual mission – workforce training and transfer-degree programs – and that’s important. But they don’t have the capacity do either very well. Increasingly, in order to meet the demands of the local economy, they’re adding more and more adjunct professors – who often have more recent workforce know-how – but this cuts into the numbers of full-time faculty that are doing liberal arts. The majority of students today want to do the transfer program, so there’s continued demand from students who want a degree. But there are also strong pressures from the economy, which wants people who are trained to do a job right now. The community colleges are really between a rock and a hard place.

What do the private-for-profit entities bring to the mix?

Kirst: Most of these programs are certificate rather than degree-granting programs. The former is approved by the Department of Consumer Affairs – it’s like running a restaurant. Nimble private operators are filling these supply-and-demand gaps, but without any serious oversight or quality control. Indeed, we are genuinely ignorant of what these programs are doing: the quality of their staff, the numbers of their students and graduates.

Your book talks about “cross-pressures” degree-granting institutions are experiencing between commitment to providing a broad liberal education and attention to marketable skills. What will be the effect on these institutions if they cater more toward marketable skills?

Scott: The university and liberal arts colleges are a unique societal resource in charge of long-term stewardship of basic research and advancement and preservation of knowledge. And that’s their distinctive mission. If they don’t do it, there won’t be anyone to do it. On that resource, the whole development of our democratic political system and our modern economy is based. Without educated citizens, our democracy is in peril; without that basic research conducted 30, 40 or 50 years ago, the things we’re seeing now in industry could not have happened.

Universities like Stanford, with their strong programs in engineering and computer science, currently have sufficient resources to serve both the market and liberal arts agenda. But most schools can’t do that. We see a steady shift over the time of our research in the proportion of degrees granted in vocational or professional areas, as well as in the ratio of adjunct to tenure-track faculty.

Your research covered 45 years of Bay Area higher education. What is unknown?

Kirst: A lot. Of the more than 350 schools we examined, only about one-third are degree-granting and covered in a national database [National Center for Educational Statistics]. We have very little information about the characteristics and functioning of the very large post-secondary educational sector in this country.

Scott: In many cases, we don’t know much about the systems that are providing the education. If you examine their websites, in some cases, we found that the same person is listed as the officer in charge in four different systems! We don’t know much about the number of students served or the quality of their education or training.

What measures can be taken to fix this problem?

Kirst: Well, first, there is not one but many problems. The beginning of wisdom is the recognition of the complexity of the educational systems at work. Also, we need to raise awareness of the current state of higher education. National polling data regularly find that the public is attentive to and dissatisfied with K-12 schooling, but much more sanguine about higher education. Most problems are attributed to the student, not to the system.

Scott: But our book also contains many specific recommendations that we think could make a difference. Mike and our colleagues worked hard on our last chapter which details useful next steps, ranging from increased state funding and oversight to the creation of regional-level systems to gather information, plan and better coordinate educational providers.

Richard “Dick” Scott is a professor emeritus of sociology at Stanford University. Michael W. Kirst is a professor emeritus of education at Stanford and current president of the California State Board of Education.