Stanford’s Hennessy and Berkeley chancellor kick off online learning summit

Stanford President John L. Hennessy and U.C. Berkeley Chancellor Nicholas Dirks kicked off a weekend gathering of 150 leaders in education, industry and government who came together to talk about the future of higher education.

Online courses may not have overwhelmed undergraduate education in a disruptive “tsunami,” as once predicted. But Stanford President John L. Hennessy, speaking at a summit on online learning on Friday, April 15, said it is a time of “great experimentation” and called for new research to help measure effectiveness and establish best practices.

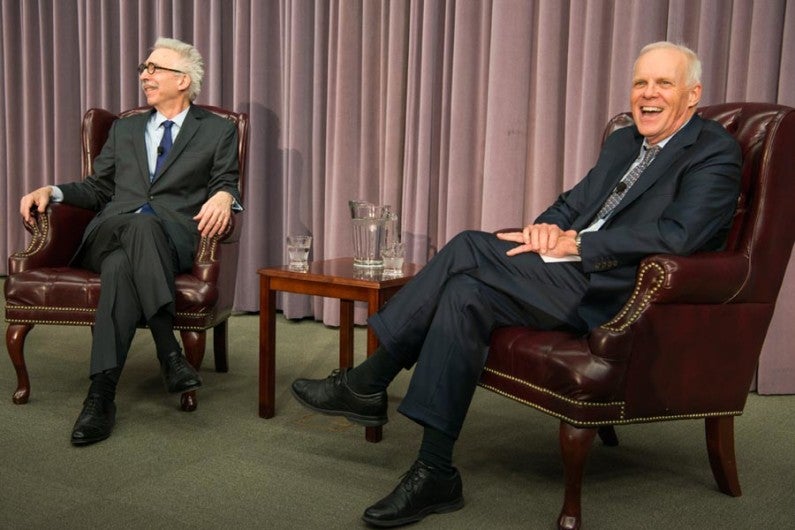

John Hennessy and Nicholas Dirks discuss higher education at the April 2016 learning summit. (Image credit: Steve Castillo)

Hennessy offered his remarks during a conversation with Nicholas Dirks, chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley. The two higher education leaders kicked off the fourth annual learning summit, an invitation-only gathering of about 150 leaders from higher education, industry and government.

This year’s summit, held at the Jen-Hsun Huang Engineering Center on Stanford’s campus, was titled “Inventing the Future of Higher Education.” Sponsored by Stanford, Berkeley, Harvard and MIT, the summit, which began Friday evening and continued through Saturday, April 16, included sessions on such topics as lifelong learning, digital humanities, the role of the professor in the digital world, the future of academic credentials and responsible use of student data.

Teaching and learning technology is “going to change the landscape of everything we do,” Dirks said during Friday’s kick-off conversation with Hennessy.

“We’ve seen that online resources can be very important,” Dirks said. “But at the same time they don’t substitute for being there” – for personal contact with faculty or the sense of community that residential undergraduate institutions provide. So far, he added, MOOCs have been “most spectacularly successful for students who have graduated.”

Hennessy concurred, observing that massive open online courses (MOOCs) have gained their greatest traction among professionals already working in their fields.

Hennessy referred to “several things that are a little worrisome” concerning online education. He cited, for one, a recent edX study on student attention spans, which it pegged at 6.5 minutes. Many students believe “they are the world’s best multi-taskers,” he said, but “in fact they aren’t very good at it.” If online education is to succeed, “you have to make sure you get students to really pay attention to the material.”

Hennessy also cited research indicating that mentoring, coaching and faculty interaction are key to success in competitive university settings, particularly for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. That’s a cautionary tale, he said, as campuses seeking to attract and retain such students also contemplate putting more pedagogical materials online.

Dirks agreed that personal attention is required to help such students succeed. However much we may envision robots, artificial intelligence or virtual reality as boons to education, he said, “we know that for a very long time we will still require the presence of real people in real time.”

The two leaders discussed a number of ways that technology can be a pedagogical asset. It could be used to help educators gather data on how students learn, they suggested, to flag gaps in student understanding and intervene appropriately, and to help students improve their writing. In a more futuristic vein, high-quality virtual-reality experiences – though “incredibly expensive” to build, Hennessy cautioned – might be used to foster empathy in students or immerse them in cultural differences.

On the nearer horizon, Dirks spoke of inserting online modules into the curriculum as supplemental material, “without disrupting the fundamental principle of residential education.”