Coyotes on the Stanford campus

Recent coyote sightings on the Stanford campus have sparked questions about the animals and what to do if confronted by one.

Have you seen a coyote strolling around the Dish? Or caring for its pups? Or hunting for rodents?

Stanford community members have spotted coyotes on campus in recent weeks. (Image credit: Getty Images)

Some members of the Stanford community have spotted coyotes roaming campus in recent weeks, leading to questions about the animals.

Stanford lands are home to many coyotes, as well as other wildlife. While the sight of a wild animal may cause alarm, Stanford’s conservation experts say that our animal neighbors are generally harmless to humans and that university lands are safe. Still, they recommend caution.

Stanford’s wildlife conservation efforts are led by the Conservation Program within Lands, Building, and Real Estate. In this Q&A, Alan Launer, director of conservation planning, and Katie Preston, conservation program coordinator, explain the recent coyote sightings, what to do if confronted by an aggressive coyote, and what Stanford is doing to protect the animals and other local wildlife.

Why are Stanford community members seeing coyotes on Stanford lands?

Katie Preston: Coyotes are a native California species; they’ve been around throughout the Holocene (the last ~11,700 years of the Earth’s history), long before European colonization. They have been able to adapt really well to urban and suburban environments and are very plastic in their needs. For example, they can find food or shelter in open and wild spaces – where you would expect to see them – as well as in developed areas, like Stanford, and in even more urban areas such as the city of San Francisco.

Alan Launer: We see coyotes all the time, both in the foothills and on the main campus. They’re smart animals, like dogs, and are here to stay.

Are coyotes dangerous and what are their normal behavioral patterns?

Preston: For the most part, coyotes are not dangerous. They can be territorial and protective, particularly between the months of May and September when they have pups. But they’re generally not to be feared. That said, being aware of coyotes is important.

Launer: Coyotes are most active during dusk, dawn, and nighttime. If you see one, it should be slinking around, all-the-while watching to see what you’re doing. While they may not run away completely, they should keep their distance. They should not appear tame and should not approach people.

Coyotes can be good neighbors to have because they provide rodent control by eating rats, mice, and other problematic species. They have been known to eat other small animals, including domesticated dogs and cats. Do not feed them! Coyotes are always hungry and if there is a food source around, they will find it.

What are signs of a problematic coyote?

Launer: A problematic and aggressive coyote might raid garbage cans or pet food stations. It might also approach someone who’s offered them food. Coyotes are similar to dogs, but they should not behave like domesticated dogs. A coyote that does behave like a house pet and is following or approaching you is cause for concern.

What should I do if I encounter an aggressive coyote?

Preston: Do not run. Stand your ground and make yourself appear larger. Shouting and throwing rocks at coyotes will help deter them.

Launer: If you feel threatened, call 911 and then get to safety. If an attack results in injury, such as bleeding, seek medical attention. There’s a chance a coyote could be rabid, so you’ll need to seek treatment.

Preston: If you or your pet are attacked by a coyote, you can also report the incident to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

What happens after I report an aggressive coyote?

Launer: Depending on the circumstances, a report to Santa Clara County Vector Control may trigger an investigation by their personnel or may involve the state Department of Fish and Wildlife. Stanford’s Department of Public Safety (DPS) may also get involved. DPS, or a private resident, also may request the services of a pest control company to euthanize the animal.

What other potentially harmful wildlife might people see on Stanford lands?

Coyotes live here, we can’t get rid of them, so learning to coexist with them is key.

—Katie Preston

Launer: Mountain lions do occasionally come through the lower foothills of campus, but we rarely see them. In California, mountain lion attacks on people are very rare. But be cautious. If you’re out in an open space with your child or dog, don’t let them run too far ahead of you. Is it likely a mountain lion will eat your kid or your dog? Absolutely not, but you also don’t want to tempt fate.

It’s also tarantula season. The males are wandering around looking for a mate, so be aware of those when you’re hiking around the Dish. They’ve got some good fangs, and a bite will be like a bad bee sting. There are also ticks and poison oak on or around campus.

Preston: Stanford lands are generally safe and, for the most part, there’s nothing to fear out there. The odds of having a negative interaction with an animal are against you unless you’re seeking that out. Turkeys might be the most aggressive animal out there, and they’re not that aggressive.

Do you know of any significant animal attacks on Stanford lands?

Launer: Not on humans. However, there have been incidents where mountain lions have killed goats that were brought in for vegetation management. And a mountain lion attacked a horse on the old Piers Ranch (when it was still operating on Stanford land). The state was brought in to investigate that incident and concluded that while the horse suffered minor injuries, apparently the horse landed a couple of good kicks and the mountain lion was not seen again.

What is Stanford doing to protect coyotes and other animals on university lands?

Launer: The Conservation Program is very active and the university has been conducting conservation activities for decades. Much of our work focuses on helping to minimize the university’s impact on local biological diversity and conducting work that will actively enhance the area for native biodiversity. This includes wildlife monitoring and land management, such as removing invasive species like stinkwort. In addition to coyotes, our work helps conserve species like California tiger salamanders, California red-legged frogs, steelhead, and other creek-dwelling organisms, as well as the creeks themselves. That said, we don’t specifically have measures that target coyotes for conservation, but many of the actions we conduct benefit local native biodiversity, including coyotes.

Preston: Two years ago we built ponds in the foothills to serve as California red-legged frog habitat. They’ve since attracted other animals, including a family of coyotes that lives nearby and enjoy playing, swimming, and exploring the ponds.

Coyotes live here, we can’t get rid of them, so learning to coexist with them is key.

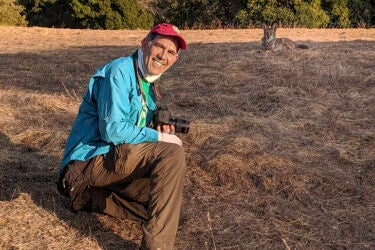

More details about Stanford’s conservation work are available on the Conservation Program website. Following is a slideshow of coyotes on Stanford lands taken by Robert Siegel, professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford School of Medicine, as well as images captured by a wildlife camera, courtesy of the Conservation Program.

Image credit: Robert David Siegel

Image credit: Robert David Siegel

Image credit: Robert David Siegel

Image credit: Robert David Siegel

Image credit: Robert David Siegel

Image credit: Robert David Siegel

Image credit: Robert David Siegel

Image credit: Robert David Siegel

Image credit: Kyler Siegel

Image credit: Stanford Conservation Program

Image credit: Stanford Conservation Program

Image credit: Stanford Conservation Program

Image credit: Melissa De Witte