Religion professor asks graduating seniors to choose ‘solidarity over rivalry’

Professor Theophus “Thee” Smith of Emory University used science fiction as a metaphor for how students might approach their interactions in the real world.

Taking a page or two from Ursula K. LeGuin and borrowing scenes from The Matrix and the Star Trek television series, a theologian/science fiction aficionado offered advice to Stanford’s next generation of graduates.

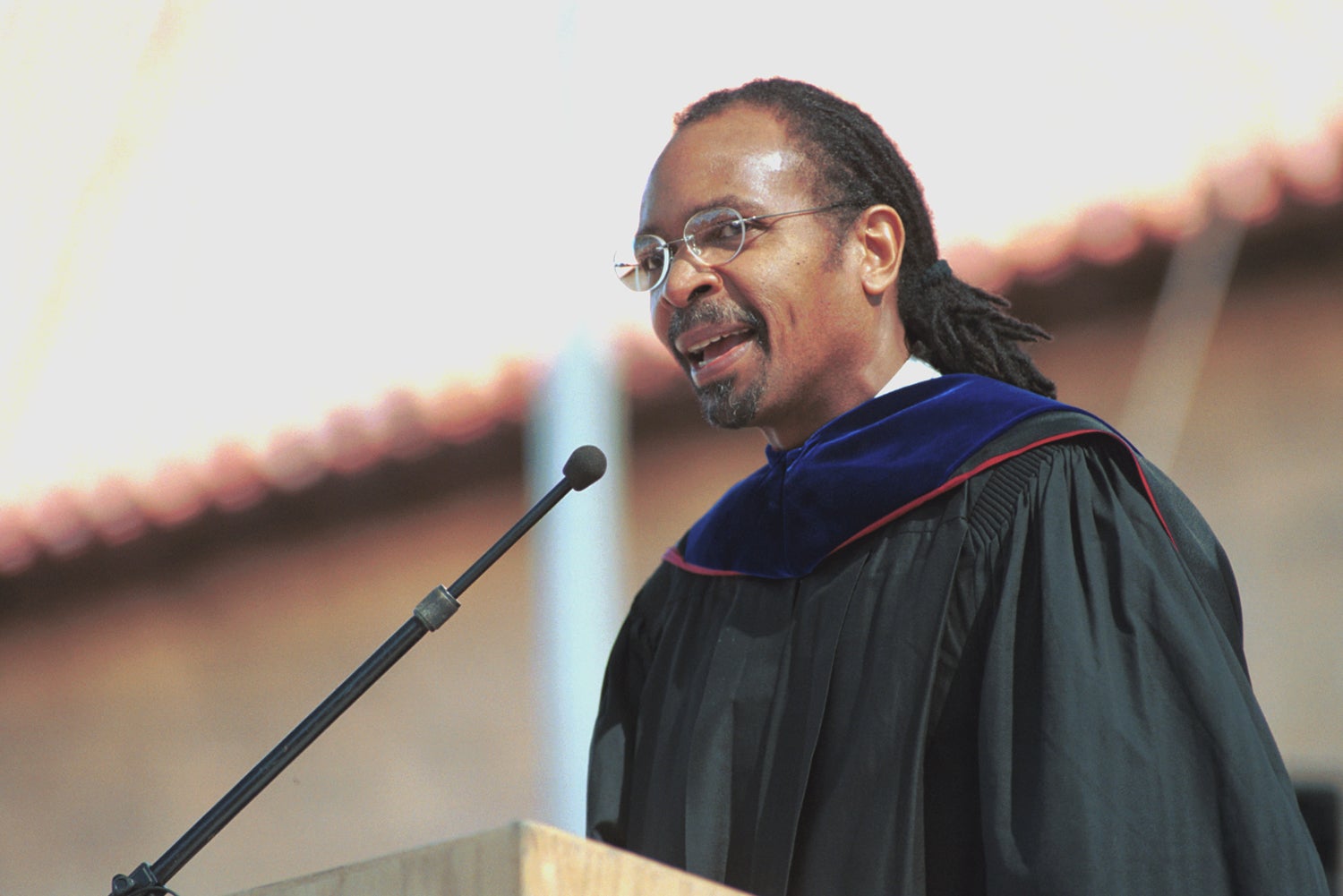

Theophus Smith, professor of religion at Emory University, addresses the Class of 2000 at the Baccalaureate Celebration. (Image credit: Rod Searcey for Stanford News Service)

In Saturday’s Baccalaureate Celebration address to Stanford’s Class of 2000, Professor Theophus “Thee” Smith of Emory University used science fiction as a metaphor for how students might approach their interactions in the real world.

And with his blessing, the professor of religion left the more than 1,700 graduates with the hope that they’ll choose solidarity over rivalry.

“May you also discern what your education and privileges are for, so that you too may become not just one more rival among others, but a living icon for the rest of us to see what it means to be a human being in solidarity with others,” Smith said.

In the Inner Quadrangle under a relentless sun, Smith navigated visitors through “The Two Spirits: Managing Angelic Rivalry for the Next Millennium,” a speech in which he offered an analysis of the violence at Columbine High School and the true message of the blockbuster film The Matrix.

In the film, star Keanu Reeves, clad in a black trenchcoat, fires multiple automatic weapons in computer-simulated shooting sprees. “The claim is that the film induced the youths to reenact its fabricated world of violence — thus in contradiction to its effort to counteract pseudo-reality, the film appears to have become a contagious source of pseudo-reality.”

Smith also touched on the work of Stanford Professor Emeritus Rene Girard, who indicated that the conflicts of individuals arise from imitating the desires of their models. Smith wondered why “that spiritual distemper endemic to our species” holds our imagination captive — to the point where even in science fiction the extraterrestrial species participate in rivalrous behavior.

“For all their anatomical, genetic and personality differences, Star Trek‘s Vulcans, Klingons, Romulans and, yes, all our storied characters throughout history, appear just as driven as we are by rivalrous desire,” Smith said.

In contrast, the work of New Testament theologian Walter Wink is about a non-rivalrous way of being, Smith said. As he led his listeners through the exercise of imagining such a state, Smith pointed out that spiritual powers aren’t based in heaven or “out there somewhere,” as in traditional religious belief.

Wink portrays “the principalities and the powers” — the familiar term from the King James version — as the inner character, or the “interiority,” of our institutions and relationships, as opposed to describing them in traditional terms such as external or supernatural beings. “Instead they exist integrally both inside of us and between us — at the center of political, economic and cultural institutions of our day.”

Smith localized his remarks by noting that some graduates will begin corporate careers with the financial resources to pursue a privileged lifestyle so highly touted in the “gold rush” that is Silicon Valley. He worried that those trying to exercise a social conscience by working in public service or for nonprofit agencies will find the challenges too daunting.

“Will paying off your student debt, or meeting your parents’ high expectations, or meeting your own ambitions regarding salary, career and prestige overwhelm your ability to act in human solidarity with those who are less privileged?” Smith asked. “How will you counteract the power of our collective wealth to fabricate a pseudo-reality for us, making us forget the vast majority of the world’s people who are living an altogether different reality?”

One can prevent the captivity to the spirit of rivalry, he said, by practicing a new asceticism, a set of practices that would function like a type of spiritual cleansing.

“Our new training … would help us realize that if we are in rivalrous conflict with someone, then help is immediately at hand in the persona itself of the rival,” Smith said. “From this perspective it is not a pious platitude but a management strategy to love your enemies. Thereby we outwit a spiritual power that uses our desires to manage us against our best interests.”

Cultivation of the spirit was also high on the list of physics major Shaffique Shiraz Adam, who in his student reflection lamented that his formal Stanford education did not prepare him for establishing a relationship “with God, my family and friends.”

Adam, a native of Kenya, advised his fellow graduates to pause a second before joining the rat race of real life and decide what is fundamentally important to them.

“And second, we should agree as a community that if the human experience is as important as experimental data, then there is the need for the modern university to increase its appreciation of the spiritual and religious dimensions of life,” Adam said.

The annual ceremony drew more than 2,000 who participated in prayer, listened to readings of works by Howard Thurman and Abraham Joshua Heschel, exchanged signs of peace and sat in rapt attention as Talisman a cappella’s high notes rose toward the heavens during “Amazing Grace.”

The baccalaureate concluded with a drumming blessing by Stanford Taiko and the recessional Hornpipe from Handel’s Water Music performed by the Bay Brass Quintet.