November 2, 2016

Stanford acquires a major collection of Nobel poet Joseph Brodsky’s papers

The Hoover Institution’s recent acquisition shows the Russian writer’s long love affair with the English language.

By Cynthia Haven

When the Soviet Union expelled the Russian poet Joseph Brodsky in 1972, he already had a few friends waiting for him in the West. One of them, Diana Myers, would remain a confidante until the Nobel laureate’s death in 1996. The London home she shared with her husband, the translator Alan Myers, became his English pied-à-terre.

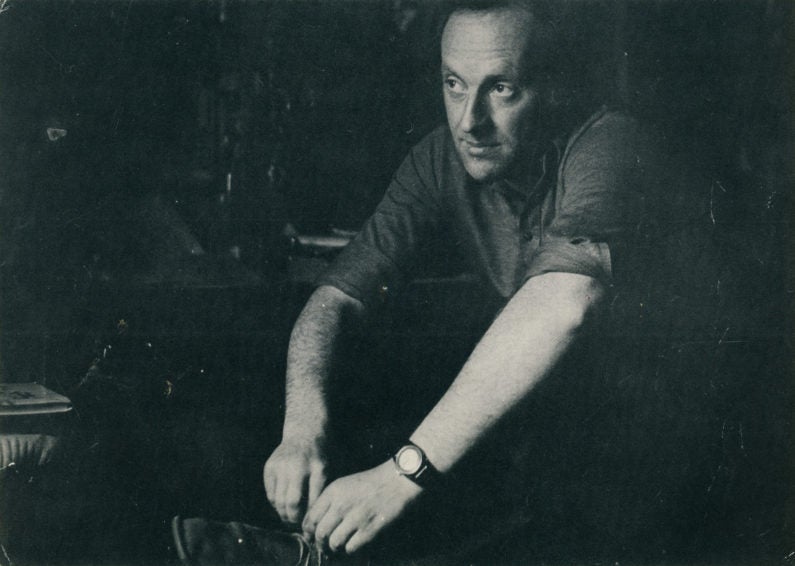

Joseph Brodsky is shown in Leningrad in 1972. (Image credit: Courtesy of Lev Poliakov)

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives at Stanford has recently acquired Diana Myers’ collection of Brodsky’s papers, including letters, photos, drafts, manuscripts, artwork and published and unpublished poems.

“We were keenly interested in adding the Joseph Brodsky papers collected by his friend Diana Myers to our vast archives on Russia and making them accessible right away,” said Eric Wakin, the Robert H. Malott Director of the Hoover Library & Archives.

“With Hoover’s significant holdings on the poet in its Irwin T. and Shirley Holtzman Collection, and the recently acquired Joseph Brodsky papers from the Katilius Family Archive at the Green Library, we’re honored that Stanford has become a notable center for Brodsky studies in the United States.”

The new acquisition documents Brodsky’s long love affair with the English language.

“I am a patriot, but I must say that English poetry is the richest in the world,” he once told an American student visiting Leningrad in 1970 – strong words for the man who would become one of the preeminent Russian poets of the last century.

Brodsky, who settled in the United States, was fascinated by the metaphysical poets of the 17th century. His landmark poem “Elegy to John Donne” was written in 1962, when he knew very little of Donne’s work. It brought him international attention. He began translating and writing English poetry during his 1964-65 internal exile in Norenskaya, near the Arctic Circle.

When the newlywed Myers arrived in London from the Soviet Union in 1967, she was carrying an armful of flowers to lay at the feet of John Donne’s effigy in St. Paul’s Cathedral. The specific request from Brodsky was her first stop in her new homeland.

In a letter Brodsky wrote to Alan Myers a few months before his exile, he requested more information about George Herbert, Richard Crashaw and Henry Vaughn. He sought guidance in finding the best editions of Ben Jonson, Henry King, Walter Raleigh and John Wilmot. An undated and unpublished poem in the collection seems to be an experiment written under their sway.

On another page in the collection, he adds his own illustrations to a few passages from Shakespeare, who anticipated the metaphysical poets.

Fifteen pages of holograph poems in the collection document the slow progression from an idea to a finished poem, with notations, corrections and amendments – all likely of interest to Brodsky scholars. “You can see how it worked, to the final version,” said archivist Lora Soroka. “It’s something that gives insight into his work.”

“It’s everyday life – everyday life when he was there, in England,” she said. “This is definitely our star collection – not big, but stellar.”

The collection also includes 70 letters from Brodsky, as well as correspondence to him from such figures as Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Swedish translator and author Bengt Jangfeldt, Australian poet Les Murray and others; 25 pages of notes and drafts; five self-portraits, a landscape, and a still life, all in black chalk; an elaborate wedding card he created and illustrated for the couple; a transcript of his 1964 Soviet trial for “parasitism;” and other records.

A selection from the Joseph Brodsky papers is included in the current exhibition Unpacking History: New Collections at the Hoover Institution Library & Archives, at the Herbert Hoover Memorial Exhibition Pavilion until Feb. 25, 2017. For more information about hours and access to the collections, visit the Hoover Library & Archives website.

-30-

|