|

July 16, 2014

Stanford poetry scholar offers new perspective on China's revered female poet

In the first comprehensive study in English, East Asian languages and cultures Professor Ronald Egan argues that the poetry of 12th-century writer Li Qingzhao has been consistently misrepresented due to centuries of gender bias. By Tanu Wakefield

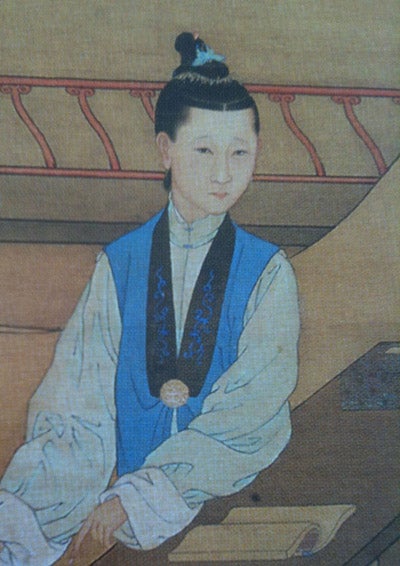

Li Qingzhao, 12th-century Chinese poet, is the subject of a new book by Ronald Egan, Confucius Institute Professor of Sinology at Stanford. (Courtesy of Ronald Egan)

Li Qingzhao was an anomaly in a literary world dominated by men.

One of China's best-known poets, she wrote during the Song Dynasty in the 12th century, when Chinese women would have been actively discouraged from writing. Yet she was determined to create a place for herself in the male literary tradition.

A beloved Chinese national treasure whose works are still read widely today, Li Qingzhao wrote prolifically throughout her lifetime. Her oeuvre includes song lyric poems, a now infamous critical essay on the song lyric form, political poems and an unorthodox biographical account of her life.

Although Li Qingzhao's poetry and criticism have gone relatively unstudied by Western scholars, Ronald Egan, the Confucius Institute Professor of Sinology in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at Stanford, has spent the last decade examining her life and writings. His latest book, The Burden of Female Talent: The Poet Li Qingzhao and Her History in China (Harvard Asia Center, 2013), is the first critical treatment of Qingzhao's writing in English to appear in 50 years.

Coming from an aristocratic, scholarly family which educated its daughters, Li Qingzhao openly aspired to be taken seriously as a writer. She wrote boldly about nature, love and longing with verses like these from song lyric no. 43:

I've heard spring is still lovely at Twin Streams,

I'd like to go boating in a light skiff there

But fear the tiny grasshopper boats they have

Would not carry

Such a quantity of sorrow.

Her poems also contained political themes, and she even wrote about a military strategy board game called "Capture the Horse."

Unlike traditional Chinese scholarship, Egan's groundbreaking approach to investigating Li Qingzhao's life and writings examines her place in history before analyzing her literary work. Reconstructing the social and literary world in which Qingzhao wrote has to come first, Egan explained, because it enables him to address the gender biases she has faced throughout the past 800 years of Chinese scholarship and criticism.

"I can't start talking about my understanding of her literary works," Egan said, "until the reader sees the whole story unpacked and deconstructed. And then we can go back with all that in mind and have a fresh look at her literary works. Only by doing that can we accurately gauge her achievement as a poet."

Egan added that one of the primary aims of his research on Li Qingzhao is "to fill a very conspicuous gap in English language writing about this great writer and at the same time address problems that exist in the Chinese critical tradition and scholarship about her."

Centuries of gender bias

Li Qingzhao was already an established poet by the time she married her first husband in 1101. When he died during a military invasion of their native Northern China, Li Qingzhao was left extraordinarily wealthy and without an heir. Tricked into marrying an abusive man who was after her fortune, she sought and, remarkably, secured her own divorce, but not before she was imprisoned for seeking it.

What most interests Egan about Li Qingzhao's biographical details is how she openly recorded her experiences and her reactions to them in writing.

What also fascinates Egan is how, given Li Qingzhao's life experiences, scholars redefined her image over the centuries, "because changes in China's social history would not tolerate a powerful, erudite female poet without male attachments," he said.

Therefore, scholars read into her poems the voice of a lovesick, pining wife or a forlorn widow, Egan suggests, because those were the only socially acceptable voices for a woman to express.

But Egan argues that Li Qingzhao's work can be interpreted very differently. He challenges conventional assumptions about how a female poet would have approached her writing by suggesting, for instance, that Li Qingzhao may not have been writing autobiographically at all when it came to her song lyrics.

Li Qingzhao lived and wrote when "there were deep ambivalences in Song society about educating women, allowing women to write, and even if they did write, preserving or circulating what they produced," Egan said.

Women often destroyed their own writing or male writers would co-opt and manipulate women's poems to serve a male audience. Since male poets of the Song dynasty frequently impersonated female voices, and Li Qingzhao would have studied these poets and known their verses well, Egan posits, why wouldn't a woman writer of the same period use the same strategy?

"As far as I know, scholars writing in Chinese haven't asked these questions," Egan said.

With plans underway to translate The Burden of Female Talent into Chinese, Egan is prepared to encounter resistance from native scholars because his perspective is unlike any other book on Li Qingzhao. Nevertheless, he has been pleased by how well his lectures on the poet have been received by younger scholars at Chinese universities, especially faculty and graduate students who have been exposed to feminist literary thinking.

Pioneering writer

Egan's investigation of Li Qingzhao draws heavily from the fields of women's literary criticism and women's history by presenting the unique case of an unattached Chinese female poet who was a subversive and pioneering writer with her own dynamics and circumstances.

Egan's historical analysis, followed by translations and close readings of her poems and critical writings, supports his iconoclastic claim that she was a woman who wrote confidently and knowledgeably about the male literary tradition that came before her.

Another example to support this perspective is Li's renowned essay on the song lyric form in which she "claims special understanding of the form and denigrates the work in it by the most famous writers of the preceding generations (all male)," Egan said.

Egan said he hopes that his work on Li Qingzhao may compel more scholars to reexamine other female poets because he's now so conscious of how key historical figures and cultural icons are apt to be recreated and refashioned.

For more news about the humanities at Stanford, visit the Stanford Humanities Center, home of the Human Experience.

-30-

|