|

February 1, 2013

Stanford classics professor debunks image of the 'noble' ancient athlete

Classics scholar Susan Stephens says that modern sports may be misguided in attempting to emulate ancient Greek and Roman athletic ideals. By Barbara Wilcox

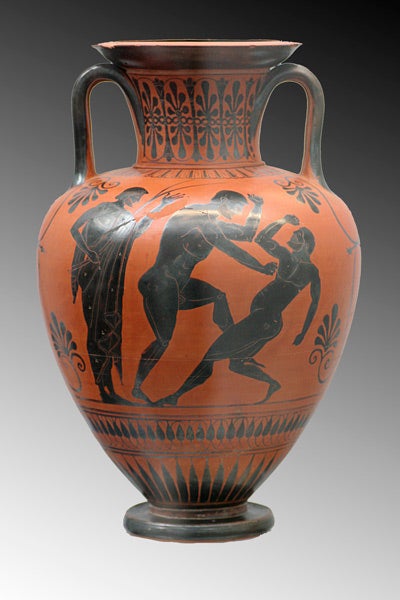

A vase, circa 500 BC, depicting ancient Greek boxers training for competition.

The Lance Armstrong doping story is just the latest athletic scandal to highlight the tension between ethical standards in athletic competitions and the drive to win. Although this tension may seem like a contemporary issue, it's actually been around since ancient times.

One of the biggest myths around ancient athletics, says Stanford classics Professor Susan Stephens, is that profiting from sports is a product of modern times.

"The notion that it doesn't matter whether you win or lose but 'how you play the game' didn't apply to ancient athletes – they wanted to win, and at all costs," Stephens said. "In reviving the Olympic Games these ancient athletes were imagined as competing solely for glory, but in the ancient games, men with rods stood around the contestants and beat them publicly if they cheated."

According to Stephens, we miss the point when we try to idealize or demonize athletes. Rather, she believes, our goal should be to try to understand the complex ways in which athletics reflects and enhances our lives and values.

Debates over amateurism vs. professionalism, the limits of proper training and the influence of social class are as old as Greece and Rome themselves. Because Greek and Roman athletics coexisted for hundreds of years, each with its own forms, contexts, ethics and adherents, Stephens says the classics are a good place to start when we want to examine our own culture's debates over sports.

"If you study anything to do with these ancient cultures, athletics was part of the social fabric," said Stephens, whose research interests include Hellenistic and Late Greek athletics. "Not only because sport was so important in Greek and Roman life, but also because so many later cultures derived their attitudes toward sports by turning to supposed Greek or Roman models."

A fantasy of 'pure' Olympics

"We have a fantasy of 'pure' Olympics" derived from the games as they were supposedly conducted relatively early, in the sixth century BCE," Stephens said. But, she added, Greek games went on for more than 1,000 years, and during that time athletics was often a path to wealth and glory. There were lots of games besides the Olympics in which athletes competed for money or other valuable prizes. It added up: On the base of a commemorative statue of a Greek athlete from the second century was noted that he had won 1,400 contests.

And although people today have a romantic view of noble Greek competitors, Stephens says that "sport was just one example of an agon, a contest. The idea was to defeat people." Competition was part of the fabric of Greek life. Musicians and singers also competed in games. The first prize for a musician at Athens' Panathenaian Games was a cash prize worth roughly the amount a skilled craftsman would earn in three-and-a-half years.

Even Greek physicians would vie against each other in public diagnoses, and Greek-speaking doctors in the Roman Empire could compete in public contests – in surgery or the use of instruments. The Greek physician Galen got his start as a doctor for a gladiator school.

"Galen was very anti-athletics," Stephens said. "In his writing, he criticizes the overtraining, the fad diets, the muscle-bound look, the immoderation that gladiators pursued in search of victory." Blood doping, we can assume, would not have been in Galen's armament of therapies. Galen evaluated his gladiatorial patients in light of a Greek ideal.

"The idea was to project a balanced, golden-mean of manliness – and still win," Stephens said. Galen's attitudes toward athletes have had a strong impact on modern ideals of amateurism.

Competitors in Greek games had to be Greek citizens, and many were of high status. It is the opposite of the Roman gladiators who competed in a huge coliseum with paying audiences imbibing a brutal and bloody spectacle. The gladiators on display, unlike the Greek athletes, were low-status, though they could become rich – if they lived.

"Why are Roman gladiators so much more interesting than Greek Olympic athletes? The answer to that question might tell us more about ourselves than we want to know," Stephens said.

Finding a body of evidence beneath the ground

"There is an immense amount of evidence for ancient sport and it is not at all obscure, though not all of it has been translated into English," Stephens said. "From Cicero and Tertullian we know the sound of the crowds, what people in the audience were saying. We have Philostratus' treatise on gymnastic training. We have the work of Pindar, whose job it was to write poems about the victors."

Hundreds of depictions of actual events like running, boxing or wrestling are found on vases or in mosaics. Archaeology from the sites of ancient games like Olympia or Nemea in Greece yields athletic facilities, starting gates and weight-training equipment. Gladiator cemeteries in York, England, and Turkey reveal the brevity and brutality of gladiator lives through gnarled bones and evidence of blunt-force wounds.

Unmarried women ran and perhaps wrestled in games held under the auspices of goddesses such as Hera in the Greek city of Argos. It's unlikely that men, who produced most of the age's writing, were allowed to watch them, and so the women's games are not very well attested.

As Christianity gained traction in the Mediterranean, Stephens said, its reaction was to condemn athletics but to appropriate the language. Some early Christians despised sports but adored sports metaphors. Paul, for instance, likens himself to a boxer (1 Corinthians 9:24-7).

Examining the role of sport in life

Stephens' winter quarter course Ancient Athletics delves into the ethical issues raised by Greek and Roman sports and how their influence plays out in Western life.

Stephens is a football fan who seriously follows the Ravens-Steelers rivalry. She enjoys having Stanford student-athletes in her classes and hopes they will come away with a greater understanding of the history of athletics and of their own roles in society. Stephens finds in the student-athlete's line of inquiry a very good way to approach ancient sport.

"If you do a sport, you have an inherent understanding of the dynamics and high stakes of winning and losing," Stephens said, "and the choices that have to be made to compete."

Barbara Wilcox is a student in Stanford's Master of Liberal Arts program.

-30-

|