|

July 14, 2011

King Solomon: Stanford scholar considers how the man who had everything ended with nothing

Scholar Steven Weitzman's new book on Solomon is a meditation on the "lust to know." But how much can we really know about the legendary king who was the first Faust and inspired the voyage of Columbus? By Cynthia Haven

Said author Steven Weitzman: "We still want to know the secrets of life." What can we learn from the wisest man who ever lived?

Maybe not as much as we think, according to Stanford Jewish studies scholar Steven Weitzman.

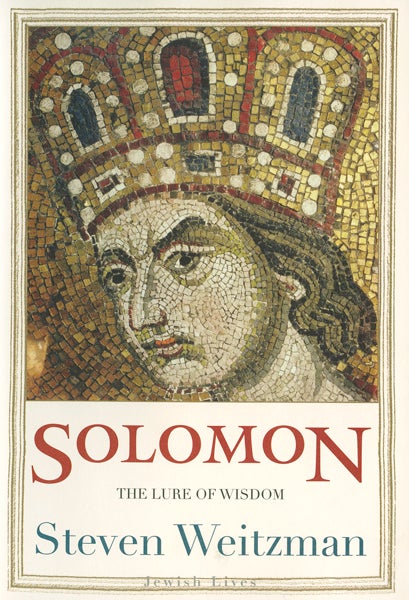

His new book, Solomon: The Lure of Wisdom (Yale University Press) has been called a meditation on the "lust to know." Yet it's curious we know so little about the man at the center of the book. We don't even know what Solomon looked like, though Biblical writers note that his father and siblings were handsome.

One thing he is famous for, though: "According to Jewish tradition, he knew everything. He knew as much as God knew," said Weitzman, a professor of Jewish culture and religion. "As a scholar, I'm attracted to knowing everything. Because I feel I don't know anything."

Hence, the book. "It was a lot of fun," Weitzman said of the work he calls "an unauthorized biography."

Solomon's legend comes down to us in many forms: Some thought he could turn lead into gold, conjure demons or become invisible. Jamaicans credit him with discovering marijuana, which they called "the Wisdom Weed."

And here's another tale: Weitzman said that Solomon is the prototype for Faust, a story that is "a crucial myth for modern times."

According to the Talmud, written in Babylon around 500 A.D., Solomon cut a deal with the devil to build the great temple of Jerusalem – with disastrous consequences.

"In order to build the temple, there were secrets he could only learn by capturing a demon. The demon gets loose and does terrible things to Solomon," explained Weitzman.

The Faust legend, adopted by Christopher Marlowe and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, is the quintessential modern metaphor to explain man's helplessness before the results of his ingenuity – whether cloning or nuclear power. "All the double-edged advances that are like letting a genie out of the bottle," said Weitzman.

The temple legend is a nice story. But is that really the straight skinny? "It's true in the way poetry is true," Weitzman insisted. "It's not true in the historical sense. It's true in its religious insights."

The "historical sense" is on shaky ground, since we don't even know the most rudimentary facts about Solomon. We date his reign to between 960 and 920 B.C., but that's only an educated guess.

Weitzman's concern is not so much in facts as the way memory "takes place sociologically with other people" and is reshaped by new circumstances. After all, he pointed out that what is universally known about George Washington – that he chopped down a cherry tree – is not true.

A powerful example of how memory shapes culture: Solomon is not only famous for wisdom, said Weitzman. "He's also famous for being really, really wealthy."

The lust for money, not wisdom, inspired a flotilla of adventurers who thought, "Gosh! If I knew what he did, I'd be really, really wealthy, too," said Weitzman. The idea launched 19th-century adventure novels that, in turn, inspired the Indiana Jones series of movies.

In fact, it was Solomon's supposed wealth that drove Christopher Columbus toward America. Looking for the wellspring of Solomon's golden treasure in the biblical Tarshish and Ophir, Columbus decided to take a shortcut to the East, circumventing all the intractable political problems in the Middle East.

It is said that when landing on the shores of modern day Honduras and Panama, Columbus happened across a native who, when asked by a translator where they were, managed to mumble something that sounded like "Ophir."

"Soon thereafter, Columbus dispatched a letter to Ferdinand and Isabella to place Solomon's gold at their disposal," wrote Weitzman.

What is most knowable is least known. Few remember that Solomon died in divine disfavor – that part, at least, comes straight from the Book of Kings. Talmudic legend has him ending as a beggar.

What went wrong? "The Bible puts the blame on a thousand wives with other gods," said Weitzman. A thousand women, many of them foreign, were probably something of an influence, or at least a distraction. But another tradition said that Solomon's wisdom itself, not the wives, led him astray.

One Talmudic tradition points to the danger of trying to outsmart God. Deuteronomy prohibits a man from too much marrying – lest "his heart will turn away" to other gods. Solomon figured that, since he knew the larger purpose, Weitzman wrote, "He could skip the part about not marrying a lot of women and just focus on the end-goal: avoiding idolatry."

It didn't work. Moral of the story: You can know too much for your own good.

According to another interpretation, "By revealing the secrets of life, wisdom removes the barriers that ordinarily confine human ambition," Weitzman wrote. Humans need limits. "If no secret or power is beyond their reach, they go too far."

Solomon's knowledge finally proved a spiritual cul-de-sac: "Knowing everything takes Solomon nowhere in the end, and if he reaches any kind of ultimate conclusion, it is only that his quest for wisdom and understanding was all a kind of delusion; he really understood nothing of value, life remained an impenetrable mystery, and even his desire for understanding was itself rooted in misunderstanding," Weitzman writes.

As Solomon himself put it, "a chasing after the wind."

But that's only if you take Ecclesiastes as his last words – or were his last words the canticle Song of Songs, which still expresses a yearning for something beyond himself? Did he repudiate all wisdom with Ecclesiastes, "giving up on a lifelong quest," or did he die with the Song of Songs on his lips – a book still full of yearning, still wanting that last metaphysical pizza? We'll never know, but both traditions exist.

One gets the feeling that Weitzman favors Song of Songs – after all, it's tough for a scholar to admit that all knowledge is a dead-end.

"The jury's out on that," Weitzman insisted. "We still have the desire to know. We still want to know the secrets of life."

Solomon's sad finale implodes his kingdom: The rulers go bad and the kingdom falls into irrevocable decline. By 586 B.C., the temple has been looted and destroyed, the king and his sons have been executed, and the population deported. Archaeologists looking for evidence of Solomon's kingdom have found nothing.

His world vanished. Corroborating evidence for the Israelite monarchy dates from the ninth century B.C., a century or so after we suppose Solomon to have lived. That's when we find the first mention of Israeli kings in other records.

Ironically, the man who knew everything falls just short of the historical record that divides the known from the unknowable. So much so that we can't even prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that Solomon existed at all.

-30-

|