|

August 19, 2011

Hoover's Soviet-era posters join acclaimed exhibit at Art Institute of Chicago

Top-notch Soviet artists and writers cranked out propaganda and boosted morale during World War II. Now their posters, from the archives of the Hoover Institution, are on view in an acclaimed exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago. By Cynthia Haven

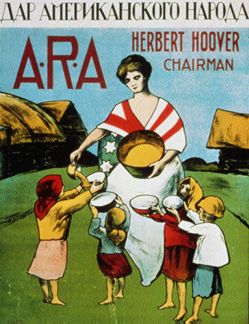

A woman, representing the United States, gives food to starving Russian children in a poster highlighting the efforts of U.S. president and Stanford alumnus Herbert Hoover to provide aid to the Russians after the First World War. (Hoover Institution Library and Archives) "I want the pen to be on par with the bayonet," said Vladimir Mayakovsky, one of Russia's foremost poets and a tireless spokesman for what he called "Communist futurism."

And for a while, it was so. The fledgling Soviet government employed top-notch writers and artists, including Mayakovsky, to crank out posters propagandizing the new era of Communism and, during World War II, pump up the morale of a badly battered nation.

In a cooperative agreement with the Art Institute of Chicago, Stanford's Hoover Institution has loaned 26 original, hand-painted Soviet posters to Chicago's current acclaimed exhibition "Windows on the War: Soviet TASS Posters at Home and Abroad, 1941-45." The exhibition continues through Oct. 23.

The Hoover Institution is well known for its collections of Soviet materials, and about a sixth of the exhibition is drawn from its archives.

"It's great exposure for one of our most important collections," said Richard Sousa, director of Hoover's library and archives.

"The opportunity to partner with such a prestigious institution and offer so many people the chance to see artistic history, firsthand, just made sense," Sousa said.

The exhibition also includes a trove of posters from TASS, the Soviet news and propaganda agency, discovered in a closet at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1997.

The survival of the posters fought heavy odds: The cheap wartime paper did not age well, and as the war dragged on, the quality of paint and other materials deteriorated. The valiant painters were reduced to using acetone and finally bedbug pesticide in place of paint thinner and turpentine on the hand-ground pigments.

For artists and writers, however, the posters provided a respite from the increasing stranglehold of "socialist realism," even though the posters were still subject to approval by layers of bureaucracy and censorship.

In particular, the creators let their imaginations roam between black humor and horror in finding ways to portray Hitler, a foreign monster who provided a distraction from the increasing dominance of Joseph Stalin, the home-grown tyrant on their doorstep.

In Soviet political cartoonist Boris Efimovich Efimov's Maneater, from the Hoover collection, Hitler is a cannibal gnawing on human bones labeled France, Greece, Yugoslavia, Romania, Poland and Belgium.

Superbestiality shows several people dressed in cow costumes crawling while the guard stands by with a whip tipped with a Nazi swastika.

While most of the posters depict the World War II period, one anomaly is a Hoover poster showing a woman, representing the United States, giving food to starving Russian children. The poster highlights the efforts of U.S. president and Stanford alumnus Herbert Hoover to provide food and aid to the Russians after the First World War. Hoover has been credited with saving more lives than any person who has ever lived. (His work during the 1921-23 famine was the subject of a recent PBS film.)

The artists' esprit and patriotism did not rescue them from the increasing vicissitudes of totalitarianism. Mayakovsky, disillusioned with the direction of the Revolution, fatally shot himself in 1930, but not before leaving a fragile legacy in paint as well as ink.

-30-

|