What an interdisciplinary creative ecosystem looks like

Ellen Oh makes spaces for synergy between artists and academics, with perspective-shifting results.

Ellen Oh understands the complexity of integrating research and practice across disciplines. As the director of interdisciplinary arts programs in the Office of the Vice President for the Arts, her role is to create the conditions for collaboration between Stanford’s academic community and visiting artists looking to expand their practice or arts-based research into new realms with consequential impact.

Here, Oh discusses the role of interdisciplinary arts on a university campus, what makes a good collaboration, and why connecting artists with academics is about more than making research look pretty.

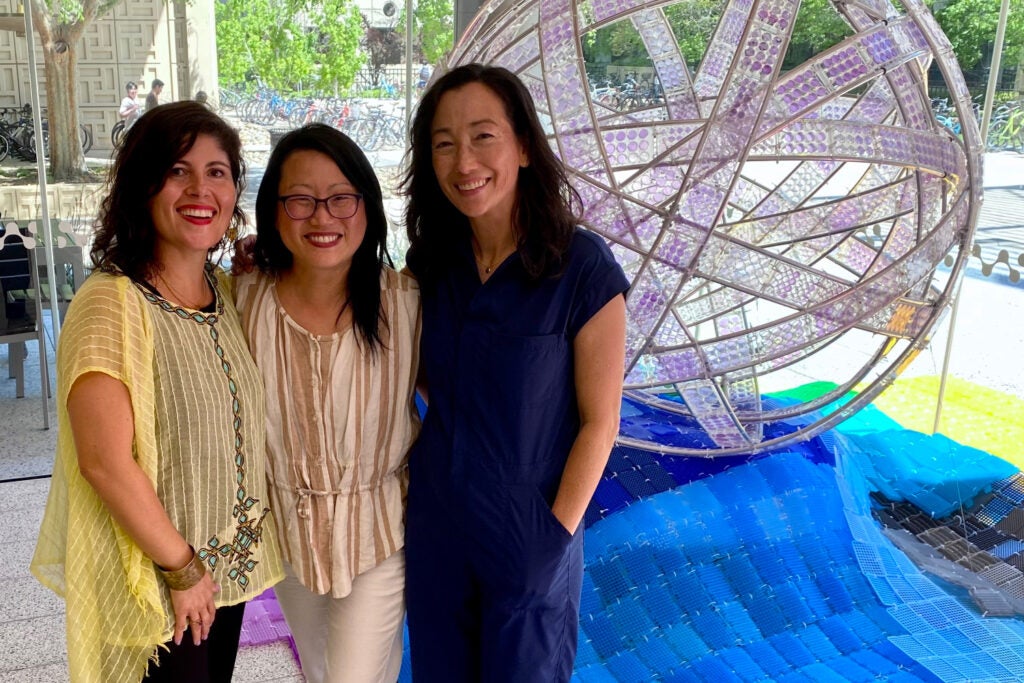

Ellen Oh (right) stands in front of Plastic Planet at the Biomedical Innovations Building at Stanford with artist Jean Shin (center) and pediatrics Professor Desiree LaBeaud (left). Shin was the 2022-23 Denning Visiting Artist at Stanford’s LaBeaud Lab. The interdisciplinary project Plastic Planet, on view through Aug. 31, highlights the paradox of science’s dependence on single-use plastic. (Image credit: Katie Han)

What is interdisciplinary arts and why is it important?

I would define interdisciplinary arts as the practice of arts within another field. Introducing an artistic approach to a field such as science or engineering can catalyze discourse, prompt new questions, and engage people with big ideas and critical issues in new ways. Applying an artist’s way of thinking can inspire innovation, social and cultural change, and help us all to imagine and build new and better futures. At the same time, allowing artists access to cutting edge research and new developments in another field can inspire their creative practice and approach to their own work.

You create the systems and infrastructure at Stanford that allow this work to thrive. What does it take to make collaboration work?

Interdisciplinary work requires a certain amount of openness from collaborators, plus time, space, communication tools, and often funding. It is not typical, yet, to have artists working in science labs or engineering departments or health care spaces, so it is sometimes a learning process for people to understand how and why artists should be involved in that work. By sharing stories and producing public programs that showcase amazing interdisciplinary work, the more people see what is possible, and the more they will recognize the value of inviting art and artists into their practice.

What have been some of the outcomes of your interdisciplinary arts programs?

For the past two years, we have hosted quarterly Art + Tech Salons, a forum for faculty, students, and visiting artists working at the intersection of art and technology to build community and learn about the broad range of activities happening on campus. The salons came about through our faculty Art + Tech working group as we were discussing the challenges of navigating these in-between spaces. That conversation led us to create new platforms, including a webpage, a Slack channel, and these salons. It’s great to see the community grow and connections being made.

The Stanford Visiting Artist Fund, established in honor of Roberta Bowman Denning is an interdisciplinary grant that’s open to any academic program or department. There is an annual application process where faculty members propose projects that involve a visiting artist, and one is selected by a jury of peers. Past artists have worked with the LaBeaud Lab in the Medical School, the Native American Studies Program, the Department of History, the Department of Theater and Performance Studies, the Abbasi Program in Islamic Studies, the Art Practice Program, and the Computer Science Department. They have done research for upcoming projects, built sculptures, developed ethical software, and staged performances. All the artists engaged with students and faculty and presented their work to the public. I am so grateful we have this endowed fund because it provides an ongoing structure that fosters some incredibly impactful work.

For example, HAI visiting artist Lauren Lee McCarthy worked on a series of projects dealing with AI, surveillance, and tech in the home and as it relates to our bodies and reproduction. She developed and presented her performance Surrogate while on campus, and also dove into AI and genetics research. Her public talks and meetings with students and faculty were very resonant as we grapple with social relationships amidst so many new technological developments.

What makes a university campus a rich environment for this kind of collaboration? What makes it challenging?

An academic environment is all about new ideas, new research and innovations, new methods and pedagogies. We have the physical infrastructure of research centers, labs, libraries, maker spaces, and arts organizations, plus the intellectual community of faculty who are thought leaders in their fields, brilliant students who are eager to learn, and built-in audiences. So it’s an ideal place for ideation and creation.

But academic institutions can be very siloed environments. Every department is in its own building, and the faculty and staff are incredibly busy with their own work. It isn’t easy to navigate and find the right collaborators, and even if you do, it is difficult to make the time to work together when people already have set priorities. It can also be challenging to understand the mutual benefit of working with an artist, and it can feel extractive to either party. Artists may feel called in to make someone else’s work “pretty,” and engineers and scientists may feel like the artist just wants their technical expertise to apply to an artwork. Good collaborators have an openness and some understanding of the other’s field and are willing to spend time learning and adapting their processes to one that is synergistic. Even if one is more about the process and the other about the product, there is something to be gained by being open to doing things differently.

How has your understanding of interdisciplinary arts evolved over time?

I used to think interdisciplinary arts was just about combining two different art forms. Now we are seeing how artists collaborate with every discipline, and we are starting to recognize artists’ practice as research. Interdisciplinary work is no longer just about adding an art component to a project as an add-on, but about co-creation and deeply integrating art research and art practice into the work from the start. Initially, our visiting artist programs and grants only attracted applications from humanities professors whose work more easily aligned with the arts, but now we are receiving more and more proposals from science, engineering, medicine, and law, which is exciting to see.