Paper in the spotlight at the Cantor Arts Center

Paper Chase showcases works on paper collected in the last ten years, including some that have never been exhibited before.

Archival pigment print. Soft-ground etching. Gelatin silver print. Black acrylic. Art on paper can take on myriad forms and expressions. Over the last decade, Elizabeth Kathleen Mitchell, interim co-director of the Cantor and the Burton and Deedee McMurtry Curator overseeing prints, drawings and photographs, has acquired a diverse collection of works on paper by artists working in the United States, Latin America, Africa, Europe and the Middle East.

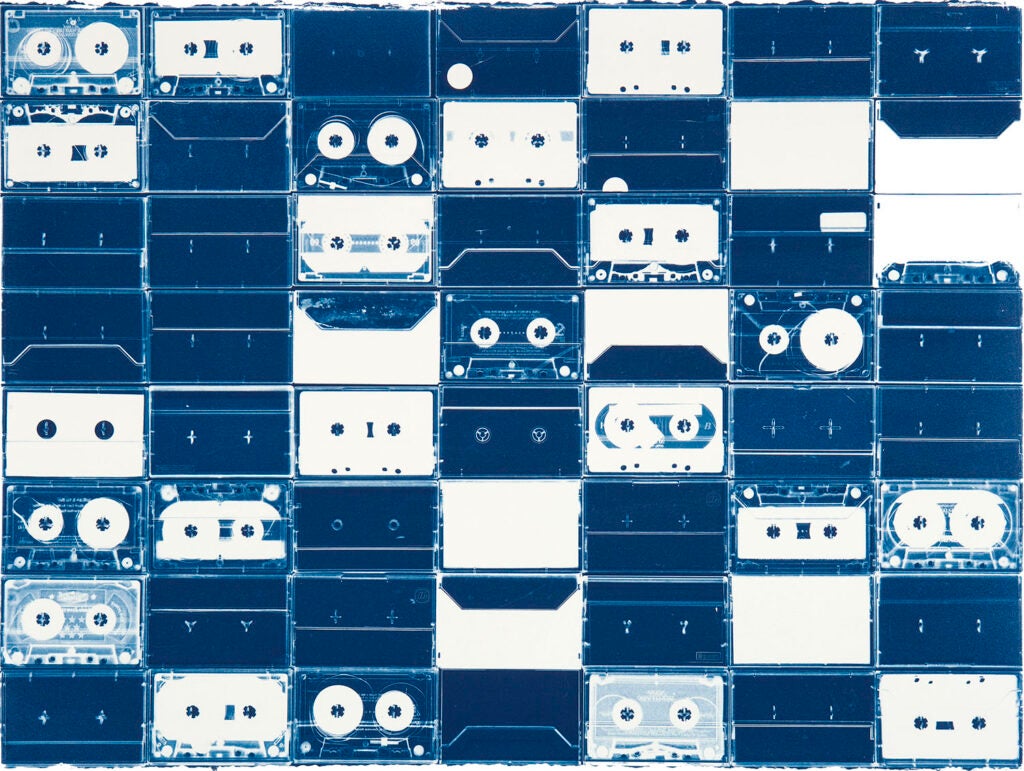

Christian Marclay (U.S.A., b. 1955), Cassette Grid No. 10, 2009. Cyanotype. © Christian Marclay. Courtesy of Graphicstudio, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Elizabeth K. Raymond Fund, 2012.569. Photograph by Will Lytch (Image credit: Will Lytch)

A selection of these acquisitions are featured in the new exhibition Paper Chase: Ten Years of Collecting Prints, Drawings, and Photographs at the Cantor. Running from Sept. 29, 2021, through Jan. 30, 2022, this much-anticipated installation features many objects that have never before been exhibited at the Cantor, including multiple works by major artists from a host of different cultures, backgrounds and countries, such as Lee Friedlander (U.S.A., b. 1934), José Clemente Orozco (Mexico, 1883–1949), Carrie Mae Weems (U.S.A., b. 1953) and Malick Sidibé (Mali, 1936–2016). The installation showcases the range and depth of the recent acquisitions and illuminates how university museums build collections for exhibitions, teaching and research.

“These works can be presented in so many different ways that they are great for teaching, whether it happens in our study room or the galleries,” says Mitchell.

Anna Bigelow, associate professor of religious studies who teaches Exploring Islam, a course that highlights important features of the Islamic religious tradition, endeavors to get students to engage with understanding cultures beyond their textual expressions. She views this exhibition as an opportunity to do that. “To see artistic productions of an individual artist or objects that are circulated within a particular culture makes things more real,” she says. “It helps to connect us more broadly beyond what we think we know.”

Bigelow is encouraged by the range of artistic impressions represented in the exhibition. “Including a more global and diverse body of artists in any conversation about what is the state of contemporary works on paper – and simply normalizing the idea that Muslim artists are part of that conversation – is extremely valuable,” she says.

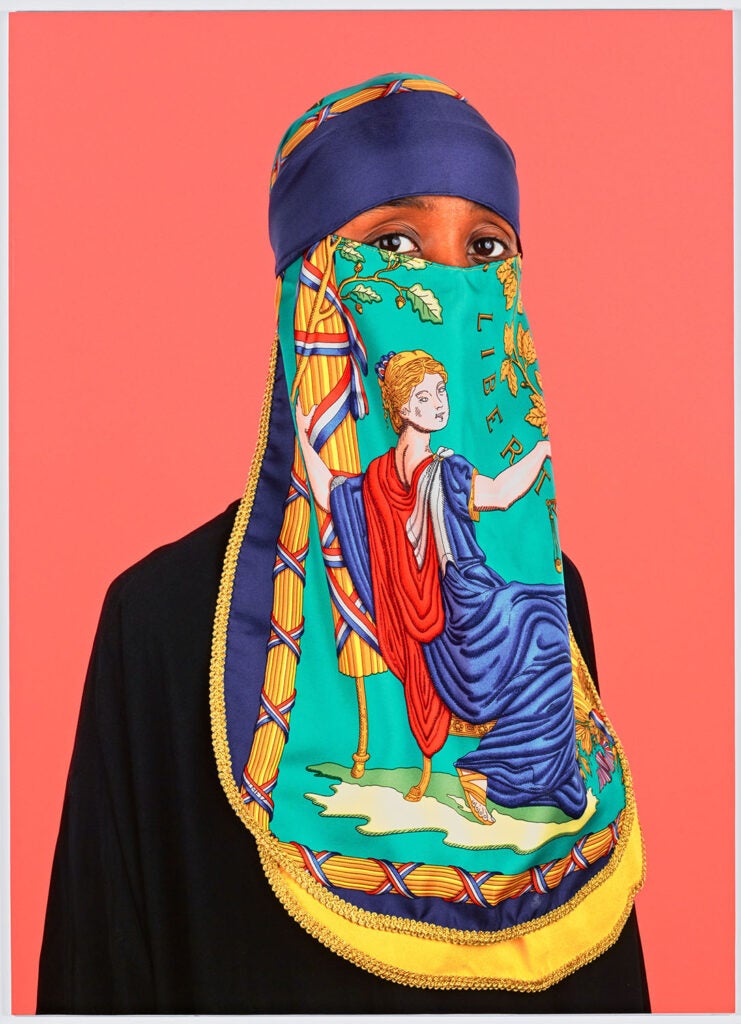

Wesaam Al-Badry (American, b. Iraq, 1984), Hermes #V, 2018. Archival pigment print. Gift of Pamela and David Hornik, 2019.3. (Image credit: Courtesy Cantor Arts Center)

The objects in Paper Chase are installed in areas and sequences that consider big concepts from many angles. Works in the Ruth Levison Haperin Gallery investigate humankind’s relationship to science and the environment. In the larger exhibition space, the Freidenrich Family Gallery, the exhibition explores collecting and collection building, personal identity and social conflict and approaches to representing history. Within these thematic zones, the exhibition homes in on more focused themes that include the measure of time, the documentation of nature, political portraits, artists’ self-portraits and representations of race, gender identity, war and migration.

The installation contains more than 100 objects, with the vast majority dating to the 20th century. Objects from multiple periods are presented together to show the long trajectory of ideas, concepts and forms, and the ways in which the exhibition uses historical objects to address contemporary issues. “The Cantor has a micro-encyclopedic collection that it has been building for 120-plus years,” says Mitchell. “My job as a curator here is to continue to push that process forward to help thoroughly represent the past while finding objects that enable people to engage with what’s important to us right now.”

The conversations sparked by exhibiting related but seemingly dissimilar objects may surprise people. Pictures by famed African American photographer Weems that examine facets of contemporary American life are presented near a set of haunting portraits of young women around the world by Pakistani-born artist Ambreen Butt that hint at what it feels like to be trapped by society, family expectations and religious extremism. Works by Iranian American photographer Shirin Neshat that expose human faces and stories through intricate frontal portraits of two Iranian citizens appear alongside Iraqi-born Wesaam Al-Badry’s provocative, covered female faces.

“There’s not one way I want people to feel or think when they visit this exhibition,” says Mitchell, “but I want them to see a range of works by artists from different moments and places, with the goal of prompting incredible conversations in the gallery.”