Collecting in support of Stanford’s teaching and research

A closer look at how three Stanford librarians approach building collections that document the past and present to inspire future scholarship.

To fuel curiosity and inspire new questions, Stanford Libraries’ collections are purposefully diverse and extensive. Three librarians showcase how archival materials, digital collections, and satellite imagery come together to comprise a research treasure trove.

Touching history

Kathleen Smith, Germanic collections & medieval studies curator

Catalog of nearly 1,000 buttons from the Overhoff button manufacturer in Ludenscheid, Germany, circa 1900. Stanford Department of Special Collections Manuscript Collection M2352 FLAT BOX 1. (Image credit: Kathleen Smith)

Displayed among thousands of rare books and manuscript boxes in Stanford Libraries’ Department of Special Collections is a German button manufacturer catalog from the 20th century. Containing almost 1,000 button samples made of brass, copper, iron, and glass used for various fabrics, the dense catalog is just one of the carefully selected items used to support the research and teaching at Stanford and for visiting scholars.

“The pieces that are collected within Germanic studies and across the other collections at the libraries are here to be closely explored and used,” said Kathleen Smith, curator for the Germanic collections and medieval studies. “That’s one of the things that I love about our library collections, they are not behind glass or locked up. We really want to get them in front of people.”

Within the libraries’ holdings, which exceed 12 million items, are digital and physical materials shared across more than 15 libraries on campus. Each collection, like the Germanic studies collection, holds materials acquired from donors, private collectors, and dealers – like the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America – as well as book fairs in California and across the globe.

With over 40 subject librarians specializing in disciplines that correspond to the academic landscape of campus, the collection development strategies mirror the needs of Stanford researchers and students.

Preserving Stanford’s story

Josh Schneider, university archivist

Grant founding and endowing the Leland Stanford Junior University (SC1445). (Image credit: Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.)

The University Archives, a unit within the Stanford Libraries Department of Special Collections, focuses its collecting on materials related to the founding and history of the University, including documentation of student life. Among items like the original copy of the university’s Founding Grant, death masks of the Stanford family, and thousands of archives from the administration and esteemed faculty, is a rich photography and media collection that captures the evolution of the university and its student body.

Thematic online exhibitions have been created to represent the breadth of University Archives, and cover topics like the history of women and activism at Stanford, as well as KZSU and student communities like Black @ Stanford, a collaboration with the Black Community Services Center.

“The University Archives exists to preserve the history of the University and make sure that history is discoverable and accessible to people at Stanford and beyond,” said Josh Schneider, the University Archivist. “Through supporting classes and research, we aim to give students opportunities to revisit, shape, and inform the documented accounts of campus life and university history,” Schneider said. This includes inviting students to help arrange and describe historical materials in the libraries’ collections.

Over the past decade, the libraries have invested in expanding access to their collections by increasing the digitization of materials. The corpus of digital materials proved vital in recent years when instruction pivoted online.

“During COVID, digital collections kept students connected to their studies,” said Schneider. “Meanwhile, our staff captured and preserved historically important university records like meeting minutes of the Emergency Operations Center, Zoom recordings of campus protests, and web archives documenting the evolving digital footprint of the University.”

In recent years, the number of collections that are born digital has increased and included resources like web archives, email, datasets, and other electronic resources. Alongside campus partners, the libraries continue to ramp up data acquisition efforts in support of scholarship across the sciences, medicine, humanities, and social sciences.

Curating satellite imagery and spatial data

Stace Maples, assistant director of geospatial collections and services

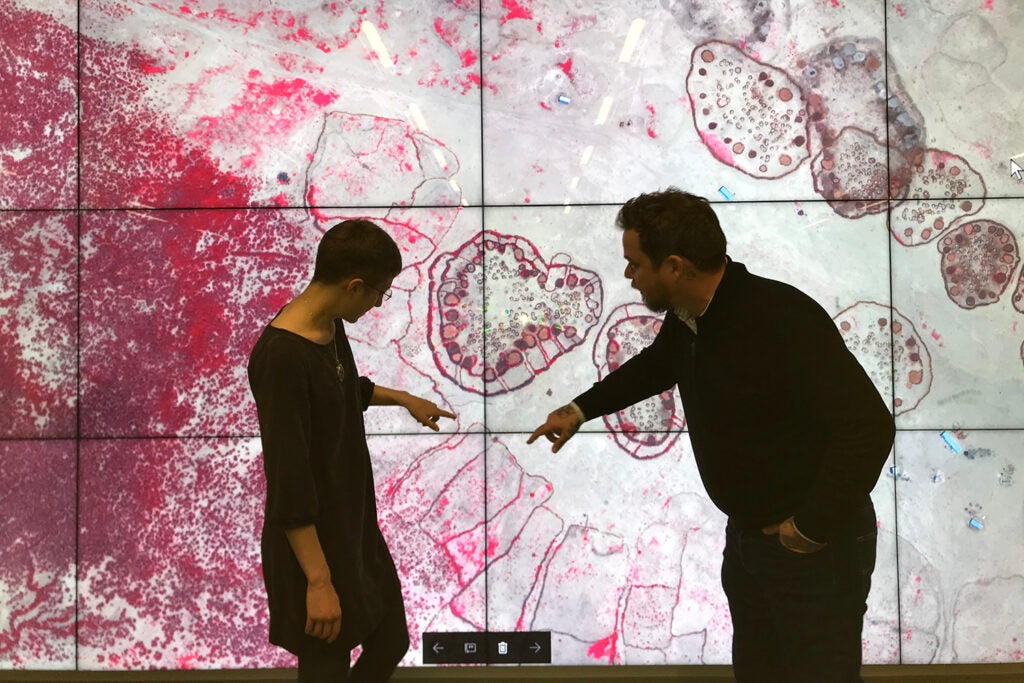

Researcher Hannah Wild and Stace Maples looked through satellite data for signs of settlements (the large circles) of the nomadic Nyangatom tribe. Absence of pink (foliage) indicates the presence of goats – and a good chance that the Nyangatom are currently in residence. (Image credit: Courtesy Hannah Wild)

Facilitating the use and understanding of spatial data, and the application of geospatial information science is core to the services offered by the libraries’ Geospatial Center. Stace Maples, who heads the unit and the libraries’ geospatial collections & services, can often be found in Branner Library shoulder-to-shoulder with faculty or students behind a powerful laptop equipped to run complex software. Maples and colleagues have hosted hack-a-thons to aid disaster recovery efforts after the 7.8 magnitude earthquake in Nepal, helped graduate students improve public health access for nomadic pastoralists using satellite imagery, and supported faculty research in agriculture and food security at continental scale, among an ever-growing list of projects relying on the expertise and resources of the team.

“Everything is, or happens, somewhere. That “somewhere” matters. We develop Stanford’s spatial data collections and services with an eye toward helping researchers augment their own data, and make their research better by considering the spatial relationships between the phenomena they are interested in,” said Maples. “This data can be anything from video and audio to images or raw numbers.”

The Stanford Geospatial Center recently licensed a global street network and point-of-interest dataset, which will be the foundation of a newly expanded https://locator.stanford.edu service. This service will allow researchers to convert the street address and placenames in their own datasets, into latitude and longitude coordinates, create distance matrices from and to thousands of locations at once, and model service areas based upon travel modes and traffic conditions.

In collaboration with the libraries’ Digital Library Systems and Services department, the Stanford Geospatial Center maintains EarthWorks, a discovery platform for Stanford’s spatial data and digitized versions of the libraries’ map collections. EarthWorks provides discovery and access to a growing collection of over 90,000 spatial datasets and digitized maps, including the collections of over 20 partner research institutions.

Building a collection also means anticipating the future needs of researchers, and the addition of satellite imagery to the libraries’ collection is but one example. Stanford was one of the first academic libraries to enter into a licensing agreement to provide scholars with access to daily, high-resolution satellite images of the earth’s lands and oceans. These types of Earth observation data will continue to prove instrumental for teaching and research.

“All of this is in support of our mission to help researchers make sense of the “where” in their own research data.”