|

September 10, 2014

Optogenetics earns Stanford professor Karl Deisseroth Keio Prize in Medicine

An idea that started as a long shot – using light to control the activity of the brain – has earned Karl Deisseroth the Keio prize in medicine. The technique, called optogenetics, is now widely used at Stanford and worldwide to understand the brain's wiring and to unravel behavior. Many researchers expect it will lead to medical discoveries. By Amy Adams

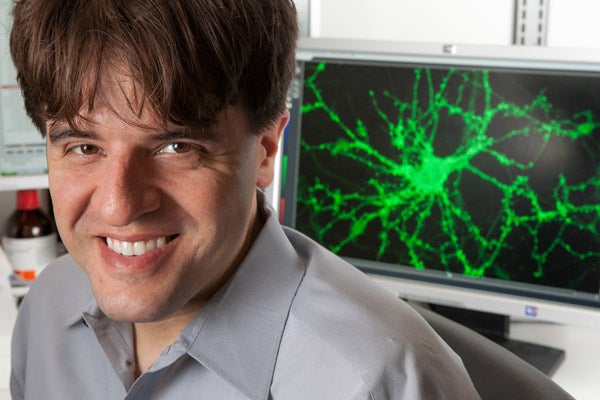

Karl Deisseroth, professor of bioengineering and of psychiatry and behavioral science, has been awarded the 2014 Keio Medical Science Prize for his groundbreaking work in optogenetics. (Photo: Saul Bromberger and Sandra Hoover)

Today optogenetics is a widely accepted technology for probing the inner workings of the brain, but a decade ago it was the source of some anxiety for then assistant professor of bioengineering Karl Deisseroth.

Deisseroth had sunk most of the funds he'd been given to start his lab at Stanford into a crazy idea – that with a little help from proteins found in pond scum he could turn neurons on and off in living animals, using light. If it didn't work he'd be out of funds with no published research, and likely looking for a new job.

Luckily, it worked, and has just earned Deisseroth, now the D. H. Chen Professor of bioengineering and of psychiatry and behavioral science, the 2014 Keio Medical Science Prize. Thousands of labs around the world are now using optogenetics to understand and develop treatments for diseases of the brain and mental health conditions and to better understand the complex wiring of our brains.

Deisseroth described the first step of his success in a seminal paper in 2005, but it was many years and many more academic papers before he could breathe easy. "There was a period of several years when not everyone who tried optogenetics got it working," Deisseroth said. "There were some people who were skeptical about how useful it would be, and rightly so because there were a number of problems we still had to solve."

Scientists worldwide have now used optogenetics to probe addiction, depression, Parkinson's disease, autism, pain, stroke and myriad other conditions.

"Optogenetics has revolutionized neuroscience," says Rob Malenka, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. Malenka is Deisseroth's former postdoctoral advisor and is now a frequent collaborator. "It has allowed neuroscientists to manipulate neural activity in a rigorous and sophisticated way and in a manner that was unimaginable 15-20 years ago."

Deisseroth adds, "I thought it would work but wasn't sure it would quite reach this point."

Lights on

Many years before Deisseroth began tinkering with optogenetics, Francis Crick – the Nobel Prize winner who co-identified the structure of DNA – had argued that neuroscience needed a tool to control one type of cell in the brain while leaving the others unaltered. Such a tool, he said, would give neuroscientists a way of turning particular groups of neurons on and off to learn more about how the brain functions.

Decades later, scientists around the world were still discussing possible ways of carrying out that vision, including some approaches using light. Deisseroth decided to build his lab's approach around proteins called microbial opsins that are found in single-celled organisms. He began with an opsin from green algae (aka pond scum) called channelrhodopsin, discovered by the German scientist Peter Hegemann.

This protein responds to light in a manner that is related to how neurons fire – it forms a channel on the cell surface that opens and allows ions into the cell. In the nerve, that channel opens when it receives a signal to fire. In the algae, it opens in response to light. If channelrhodopsin could be made to do the same thing in a neuron of a living animal it might provide a way of controlling the activity of that neuron using light – perhaps even during animal behaviors.

The concept seemed theoretically possible but risky, and indeed getting it to work in living animals took many years. Delivering the required large number of opsins into specific groups of cells within the brain, and targeting light deep into the brain, both posed challenges, and many opsins were initially not well-produced or tolerated by neurons.

When all the key pieces finally fell into place, they were able to use fiber optics to shine a tiny light onto a group of neurons harboring opsins in living animals and cause just that specific subset of neurons to either fire or be silenced in ways that controlled normal or disease-related behaviors.

"Karl had the insight to realize how important this was going to be," says Malenka, who is also the Nancy Friend Pritzker professor. "The idea had been floating around but he recognized the importance of the channelrhodopsin discovery and made it work."

Helping patients

Deisseroth believes the most important contribution from optogenetics will be its role in understanding biology and behavior, but says it will also likely contribute to medical advances.

One example of how optogenetics could point to better therapies came from work in Parkinson's disease. Deisseroth and his team used optogenetics to stimulate different components of the brain's wiring in animals with a version of Parkinson's disease, and found that connections arriving into a particular region deep in the brain, when stimulated, powerfully reduce symptoms.

Doctors who treat Parkinson's disease will sometimes implant an electrode that stimulates this brain region in patients, with quite a bit of success in reducing symptoms. But there had been debate over what wiring the electrode should stimulate. Deisseroth's work pointed to these arriving neuronal connections.

"Now neurosurgeons are finding that placing their electrical contacts to target connections gives better results in treating symptoms in people with Parkinson's and many other conditions," Deisseroth said.

Pond scum to the rescue?

Decades ago, when teams of scientists began studying the light-sensitive proteins within microbes it wasn't with an eye toward one day helping people with depression, Parkinson's disease or untreatable pain.

It was to better understand the intricate and amazing world around us. The research was fueled by pure scientific curiosity. Curiosity that has, as it happens, led to a discovery that might just help people.

Deisseroth argued in a Scientific American piece about the importance of funding curiosity-driven research as opposed to more targeted disease-focus research that some scientists and funding agencies have advocated.

"The more directed and targeted research becomes, the more likely we are to slow our progress, and the more certain it is that the distant and untraveled realms, where truly disruptive ideas can arise, will be utterly cut off from our common scientific journey," Deisseroth wrote.

He argues that funding agencies need to not only support fundamental research, but also facilitate the translation of that basic research into the work that can one day help patients.

"This is something that Bio-X does well," Deisseroth said. He works in the Clark Center that houses Bio-X, where scientists from very different backgrounds work elbow to elbow. "They put people who come from different perspectives within shouting distance of each other so those leaps can happen," he said. Bio-X has provided seed funding for a number of optogenetics collaborations and also supports the optogenetics core, where scientists can learn how to employ the technique in their own labs.

We need to be supporting people who are fascinated by pond scum and other obscure topics, Deisseroth argues, if we are to eventually treat depression, autism, Parkinson's disease and a host of other complex diseases.

-30-

|