|

December 6, 2013

Stanford researchers find merit in sub-Saharan Africans buying water from neighbors

Stanford researchers working in Mozambique point the way for an informal water practice to help solve one of the world's most pressing health and welfare issues. By Rob Jordan

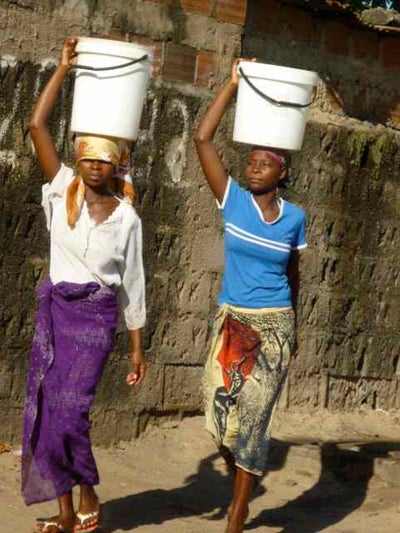

In sub-Saharan Africa, about one in five people purchase water from neighbors connected to public or private utility lines. (Photo: Valentina Zuin / Courtesy Stanford University)

In sub-Saharan Africa, more than 60 percent of city dwellers live in slums, and population pressures have led to unplanned development lacking basic infrastructure, such as water lines.

Only a third of urban dwellers have access to a piped water connection in their homes. Other sources, such as public standpipes, are often plagued by poor maintenance, heavy use and high cost due to the need for attendants and other factors. They often require long travel and waiting times, too.

As a result, about one in five people purchase water from neighbors connected to public or private utility lines. This practice, known as resale, is either illegal or informal in many places.

Stanford researchers are challenging the logic of discouraging resale. Their findings show that resale is as good or better than standpipes in terms of quality, quantity, convenience and price of water, and that current tariffs on the practice penalize the poor. The Stanford findings were published in a recent issue of the Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development.

Resale's prohibition in most of sub-Saharan Africa for public health reasons is a red herring, said studies co-author Jennifer Davis, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering and a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. "The same concerns could be raised about standpipes and public taps that are operated directly by utilities," Davis said. "Legalizing resale is generally a good thing to do, so long as appropriate water tariffs are part of the program."

At the request of the government of Mozambique, Valentina Zuin, a doctoral student in the Emmett Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources who led the research, is translating the findings into a policy and research agenda, which includes resale as a service option and a restructured water tariff. The agenda will help guide Mozambique water sector policy and infrastructure investments toward the country's goal of achieving universal urban water coverage by 2025.

Already, the Stanford research has influenced decision makers to include a water tariff reform component in a recently approved $178 million World Bank-funded project. The project will connect approximately 100,000 households in Mozambique's capital, Maputo, to the formal water supply system by expanding the city's piped-water network in unplanned areas and increasing coverage in poor inner-city neighborhoods.

Davis, Zuin and their fellow researchers make clear that the current tariff structure in Maputo, which is a typical tariff structure used in sub-Saharan Africa and beyond, penalizes the poor, including resellers and their customers, by pricing water higher for people who use it most, such as those supplying their neighbors. Resellers generally don't sell their water to maximize profit, the recently published research finds, but to meet subsistence needs, solidify relationships and reap other community-oriented benefits.

As in many other sub-Saharan African countries, resale's legal status is ambiguous in Mozambique: There is no law that either allows or prohibits it. Yet, the large majority of the population perceives it as an illegal practice. A 2011 Stanford study on the issue influenced the country's regulatory authority to launch a TV campaign to inform the public that the practice is not illegal. This has helped dispel penalty fears, and eliminated the ability of water utility employees to extort "hush money," or bribes, from those who practice resale, according to Zuin. It is also expected that resale legalization will increase consumers' satisfaction with this service option.

Manuel Alvarinho, president of Mozambique's Water Regulatory Council, credited the Stanford research team with helping lay the foundation for improving access to water for the country's urban poor. "I am very thankful to the Stanford Woods Institute, and in particular to Valentina Zuin, Jenna Davis and their team, for the high-quality work they produced, which is pioneering in Mozambique," Alvarinho wrote in an email.

The study's Stanford co-authors include civil and environmental engineering Professor Leonard Ortolano and doctoral student Kory Russel. Civil and environmental engineering graduate student Maika Nicholson contributed extensive research.

Rob Jordan is the communications writer for the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

-30-

|