|

View video here.

September 15, 2011

Compatibilism: Can free will and determinism co-exist?

Stanford philosophy professor takes the side of a beleaguered theory – that predetermination and free will are not mutually exclusive. By Max McClure

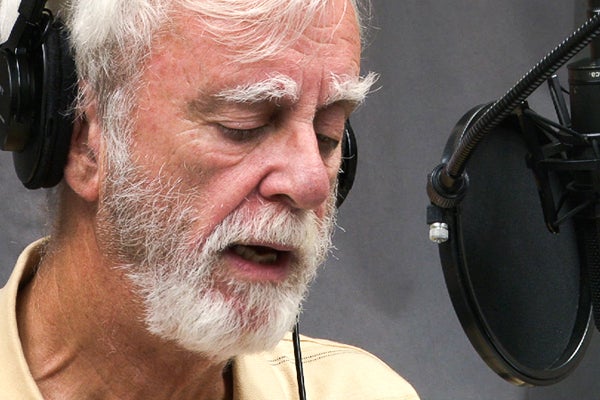

John Perry, professor emeritus of philosophy, is one of the hosts of "Philosophy Talk," the nationally syndicated radio "program that questions everything - except your intelligence." (Photo: Steve Fyffe / Stanford News Service) William James said it was "a quagmire of evasion." Immanuel Kant called it "wretched subterfuge" and "petty word-jugglery."

Compatibilism – the belief that free will is compatible with a world where every action is determined by the events preceding it – has never been an easy sell.

"I started noticing that I teach students about compatibilism every year," said John Perry, professor emeritus of philosophy at Stanford. "But every year more of them become incompatibilists instead."

He's looking to change that. Perry is a host of the nationally syndicated radio show Philosophy Talk and the author of an upcoming book in defense of the controversial theory.

Incompatibilists appeal to what may seem to be a commonsense argument: Determinism holds that every event is caused in a predictable way by events before it. Free will means that we make choices from a variety of options. If those choices are actually caused by some other event beyond our control, where does freedom come in?

It's a question that is particularly concerning when we try to assign people moral responsibility for their actions. If the actions of individuals are not free, it becomes more difficult to say that a criminal, for instance, is guilty of anything other than being composed of atoms, his actions predetermined by the laws of physics and a chain of events triggered eons ago.

Drawing on the works of 18th-century British philosopher David Hume, Perry has set out two separate responses to the incompatibilists' complaint. The key is to prove that "will not" is not the same as "cannot."

Weak theory of laws

As Perry put it, "Hume thought the laws of nature were just generalizations that hadn't been refuted." In other words, Hume wouldn't say a glass falls to the ground because some fundamental law requires it to. He'd point out that we only say gravity exists because we saw the glass fall.

While the distinction may seem trivial, Hume's view implies that the existence of gravity could be proved or disproved every time we drop something.

It also means that statements about future events are neither true nor false until they happen. "This glass will fall if I let go" is a sentence that will prove accurate or not only when I drop the glass. It's an approach that means the laws of physics are potentially redefined with every moment of existence.

Perry calls Hume's view the "weak theory of laws" and thinks it would satisfactorily resolve the incompatibilist question – by letting the "future events" tail wag the "universal physical laws" dog.

"The thing is," he said, "I don't agree with it. Hume didn't really believe in causation, but I think you can see it happening around you."

Weak theory of ability

Perry's preferred position – also based on a suggestion from Hume – rests on a clarification of how the word "can" is used.

"If you want," he said, "you can take that pen, turn it upside-down, jam it up your nose and bleed out all over the table."

But I didn't stick the pen in my nose – and an incompatibilist would say that, because of that, I can't do it at all. If we rewind the universe and play through the scene again, I will continually refrain from injuring myself, in a way that suggests I have no choice in the matter.

Perry, however, thinks that's a strange way of using the word "can." Here, the word should refer to the "repertoire of actions" that a person is physically able to perform.

"Assuming you're a relatively normal individual, I'm virtually certain that you're not going to do it. But there's a difference between you and someone who can't move their arms at all."

In essence, Perry argues that having an ability "doesn't mean as much as people think it does." It simply means that a person could intentionally do something, even if her own desires prevent her from doing it.

"Why invent a notion of 'can' that includes what you 'want' to do?" he asked.

This approach, which he calls the "weak theory of abilities," decouples "won't" from "can't" – and suggests that incompatibilism is "about the abuse of language by other philosophers."

"I think there are certain properties that have been recognized by human beings and animals long before language," he explained. "The idea of 'can' is one of them." Animals are able to intuitively base their behaviors on what they can or can't physically do, Perry said.

"And then philosophers came along and decided to define 'can' in terms of 'possible,'" he said. "That just doesn't follow."

It's possible that Perry's book, Wretched Subterfuge, could be completed next year, although the date has not been pre-determined.

Max McClure is an intern with the Stanford News Service.

-30-

|