Stanford will rename campus spaces named for David Starr Jordan and relocate statue depicting Louis Agassiz

President Marc Tessier-Lavigne and the Board of Trustees approved a campus committee’s recommendation both to remove Jordan’s name from campus spaces and to take steps to make his multifaceted history better known. Stanford also will relocate a statue of Agassiz.

Stanford will rename campus features named after David Starr Jordan and take actions to provide the public with a more complete view of his complex history, which includes not only his seminal leadership as the university’s founding president but also his parallel leadership in promoting eugenics.

Jordan Hall is home to the Department of Psychology, whose faculty members recently voted unanimously to request the name change and removal of the statue. (Image credit: Kate Chesley)

The university will also relocate from the façade of Jordan Hall a statue of Jordan’s mentor, Louis Agassiz.

The decision follows a review conducted this summer by a committee of faculty, staff, students and alumni. The university’s Board of Trustees, acting on a recommendation by President Marc Tessier-Lavigne, approved these steps:

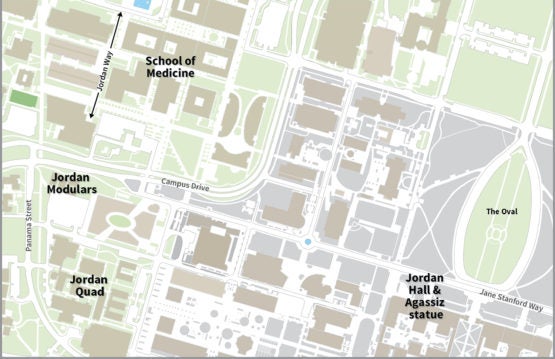

- Removing Jordan’s name from Jordan Hall, current home of the Department of Psychology; Jordan Quad and Jordan Modulars, near Panama Street and Campus Drive West; and Jordan Way in the Stanford Medical Center area;

- Relocating a statue of Agassiz from Jordan Hall to a location where it can be given appropriate context; and

- Developing an active effort to better explain the full range of Jordan’s legacy and contributions, beginning with an informational plaque in Jordan Hall and extending to additional efforts such as historical displays and educational programming. These efforts have the goal of ensuring that Jordan’s history is not removed from the Stanford campus but rather more fully articulated in ways that cannot be achieved simply by a building name.

Jordan (1851-1931) had a multifaceted legacy. In addition to being a noted naturalist and ichthyologist, he was an innovative educator and an accomplished institution-builder who played a central role in the founding and early years of Stanford University. He implemented a more modern philosophy of education, encouraged the “absolute democracy of education” and the practical arts and established the major subject system, which was an innovation at that time. He also shepherded Stanford through two major crises, a financial one triggered by the death of Leland Stanford just two years after the university’s founding in 1891, and the great earthquake of 1906.

But, as the committee report documents, Jordan was also a leader and driving force of the eugenics movement, which promoted controlled reproduction based on heritage and which helped lay the foundation for later policies of forced sterilization. Jordan wrote prolifically on the subject of human populations and advocated many policy positions, including opposing slavery and imperialism. However, the committee reported that he disparaged a broad swath of human populations and that he forcefully articulated views, unsupported by scientific evidence, of a hierarchy of races, ethnicities and cultures. He also wrote extensively about the “decay” of populations through the reproduction of groups deemed “unfit,” a view that underpinned his leadership in the eugenics movement.

Agassiz (1807-1873), who had no significant connection to the university, was a leading naturalist of his day who also promoted polygenism, which holds that human racial groups have different ancestral origins and are unequal.

Building 420 in the Main Quad, then known as the Zoology building, was named for Jordan in 1917, and the Agassiz statue was placed above the building’s entrance, facing Palm Drive, in 1902.

“No person is perfect, and the reevaluation of names of features as well as the location of artifacts should occur only in rare circumstances, based on a rigorous application of renaming principles,” Tessier-Lavigne said, referring to a set of principles adopted by the university in 2018. They include considerations such as the strength and clarity of the historical evidence, the person’s role in the university’s history, the centrality of a person’s offensive behavior to the person’s life as a whole and the university community’s identification with the named feature.

“David Starr Jordan made monumental contributions to the founding and development of Stanford, which are rightly celebrated,” Tessier-Lavigne said. “But, as the committee reported, Jordan was an equally powerful and vigorous driving force for beliefs and actions that are antithetical to the values of our campus community, and he leveraged his position as president to advance them. Those two facts were central to my decision to endorse the committee’s recommendations, as was the fact that the actions recommended by the committee do not seek to erase Jordan’s legacy, but rather to put it in proper perspective and to recognize his history on our campus in new ways.”

Community input

Tessier-Lavigne appointed the committee of faculty, staff, students and alumni in July to review and report on requests from the Psychology Department faculty and the Stanford Eugenics History Project to change the name of Jordan Hall. The Psychology faculty also asked that the statue be removed.

David Starr Jordan’s name will be removed from four campus spaces and a statue of Louis Agassiz will be relocated from Jordan Hall. (Image credit: Dana Granoski)

The committee undertook an evidence-based, research-intensive process and produced a lengthy, thoroughly documented report with scholarly rigor. It applied the principles developed by a previous committee for considering the renaming of campus features named for historical figures with complex legacies. A similar process in 2018 resulted in the decision to rename some, but not all, campus features named for Father Junipero Serra, who founded the California mission system in the 18th century.

The Jordan committee’s extensive research included reading many of Jordan’s voluminous published writings and consulting archives for primary material relevant to the issues under review. Its engagement efforts included community and alumni town halls; outreach to former biology and psychology majors, whose departments have occupied Jordan Hall; meetings with biology and psychology faculty and others working in genetics and bioethics; and consultations with historians working at Stanford on related subjects. It also reviewed more than 250 written comments.

Complex legacies

“Because of David Starr Jordan’s prominence in the promotion of eugenics and significant involvement in the American eugenics movement during his tenure as the first president of Stanford University, we believe that continuing to honor him in locations where community members work or study will undermine Stanford’s values,” the committee wrote in its report. “Retaining the statue of Louis Agassiz, who advocated against Black equality, would also damage Stanford’s efforts to ensure equity and inclusion.”

Jordan, who served as president from 1891 to 1913, used his platform as president and a teacher to advocate for eugenics policies that ultimately led to forced sterilizations, and he was instrumental in creating such institutions as the American Breeders Association Eugenics Committee. In his writings, he denigrated a litany of races and cultures, and he believed the efficacy of education was limited by genetic potential.

“While Jordan’s eugenic theories were certainly based upon a scientific error and a lack of academic rigor on his part,” the committee wrote, “he chose to advocate and work toward putting them into practice in a way that would undermine equality.”

“The board appreciated the committee’s frank assessment and agreed with the administration’s decision,” said Jeff Raikes, chair of the university’s Board of Trustees. “The legacies of David Starr Jordan and Louis Agassiz are complex and difficult. These decisions require great care and thoughtful research, particularly when they apply to individuals such as Jordan who have played an important role in Stanford’s history. We value the input that members of our community provided for this process, and we hope the process itself provides a learning opportunity for all of us in the Stanford community.”

Although renaming falls under the president’s authority, Tessier-Lavigne brought the matter to the board for additional approval because of the historical importance of Jordan to the university.

“While continuing to honor these figures without questioning them would go against our goals of inclusion, the university should pursue meaningful educational projects that enable us to know their history and their relation to the university more fully, not forget them,” Tessier-Lavigne said. “In the spirit of the university’s commitment to research and discovery, acknowledging rather than erasing difficult parts of our history will make us even stronger.”

Implications of Jordan’s and Agassiz’s views

“In David Starr Jordan’s history, we identified an unsettling connection between his advocacy for eugenics and his leadership at Stanford, and strong evidence that his influence encouraged students to put these beliefs into practice,” said committee chair Bernadette Meyler, a Stanford law professor. “But Jordan’s and Agassiz’s impact is not limited to the past, because to this day their beliefs continue to cast a shadow on our campus. A range of students and faculty expressed discomfort and shame at spending time in areas where Jordan’s name and the Agassiz statue carry such negative connotations.”

The committee found it especially troubling that Stanford’s Psychology Department, which has pioneered research proving that negative expectations can have a deleterious impact on performance and has worked to remedy that bias, is located in Jordan Hall.

Meyler and her committee colleagues asked the university to go beyond simply removing the name and statue. In their report, they encouraged the university to develop educational offerings, which might include augmented reality, educational programming and visitor center exhibits. In recommending relocation rather than removal of the statue, they noted its iconic imagery – well-known photos depicting the statue’s head stuck in concrete after being dislodged during the 1906 earthquake – and its use to demonstrate geologic principles.

Next steps

Debra Satz, whose responsibilities as dean of the School of Humanities and Sciences include the Department of Psychology, will institute a process to determine a new name for Jordan Hall, whether it be an individual’s name or a name based on other considerations. Some buildings in the Main Quad are named for individuals, others are named for subjects or disciplines and some are not named at all. Satz will bring her recommendation to the president and provost.

In the meantime, the university will remove the Jordan Hall lettering from the building as soon as practicable, along with the Agassiz statue, and the building will be referred to by its number in the Main Quad, Building 420.

Tessier-Lavigne will implement the other recommendations from the report, including establishing a process for identifying replacement names for the other features named for Jordan, if needed. The committee noted that Jordan Way, a pathway in the medical center area, has less salience than the other spaces named for Jordan and recommended that its name be changed in the course of normal university planning.

The president also will take the next steps in creating an informational plaque in Jordan Hall, and in pursuing the educational efforts recommended by the committee to ensure that Jordan’s history and contributions, and their relation to Stanford’s history, are articulated more fully to the university community and not forgotten.