French civilization, culture professor Marc Bertrand dies

Marc Bertrand, professor emeritus of French, taught French civilization and cultural history to generations of students during his time at Stanford. He died April 28 at 83.

Until his last days, Marc Bertrand was a familiar presence at Green Library, reading about French culture.

Bertrand, professor emeritus of French who taught generations of students for 34 years at Stanford, died April 28 because of heart problems at his home on campus, said his wife, Vida Bertrand. He was 83.

Despite retiring in 2000, Marc Bertrand continued to research and write about French cultural history and contemporary novels. His family described Bertrand as a worldly man who cared deeply about his students and his family. Education, his family said, was his lifelong passion.

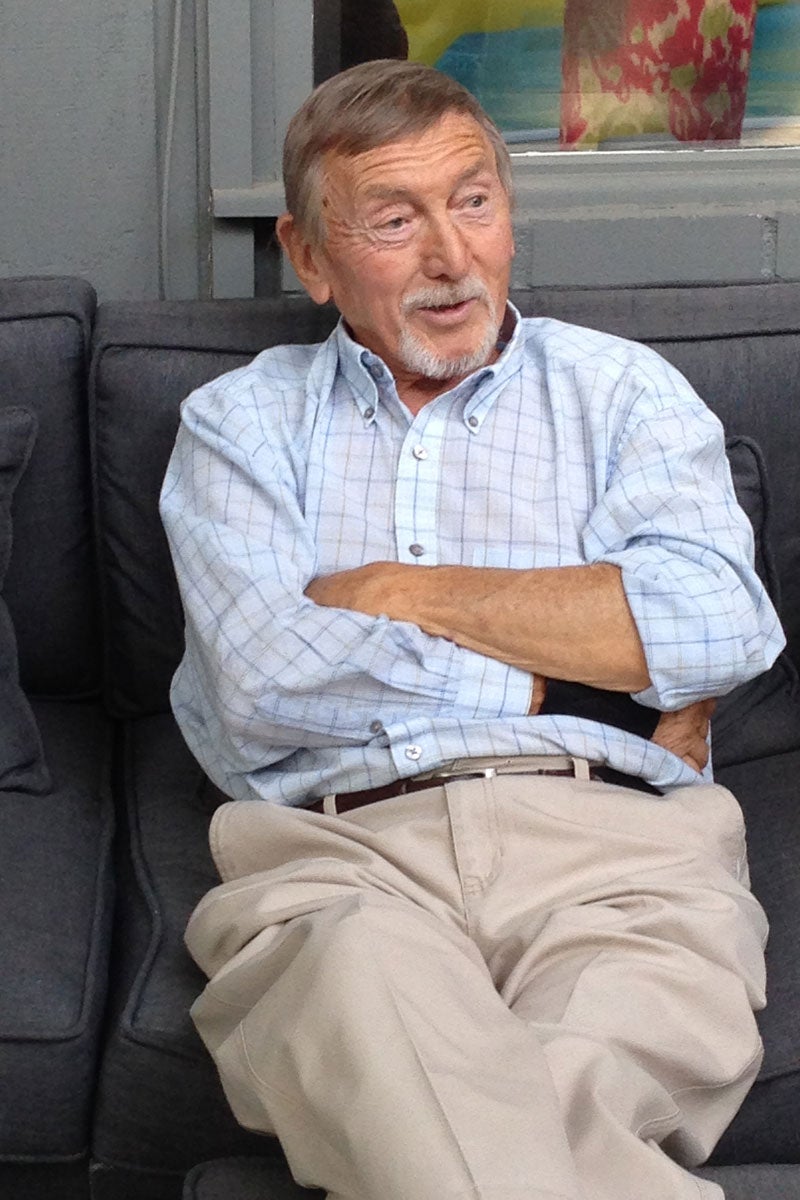

Marc Bertrand, 1933-2017 (Image credit: Courtesy Bertrand Family)

“He loved research and learning, and he always wanted to learn more,” Vida said. “It was so important to him.”

Even after retirement, Bertrand continued to teach not only Stanford students, but people in nearby communities through the university’s Continuing Studies program.

Despite his health worsening over the past two years, Bertrand would still visit Green Library almost every day to work on his research of representations of paintings in French novels, his wife said.

“He didn’t have enough strength but would still want to get up and go,” Vida said. “I had to hide his car keys a few times.”

Originally from Metz, France, Bertrand served in the French Army from 1953 to 1955 before coming to the U.S. to pursue his education. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees, as well as his PhD in Romance languages, at the University of California, Berkeley.

Bertrand came to Stanford in 1966. He became most known for his 1968 book about the work of French writer and journalist Jean Prévost, L’Oeuvre de Jean Prévost. His other works included a 1985 book called Popular traditions and learned culture in France from the 16th to the 20th century. He also wrote articles about other French figures, including Voltaire, Gustave Flaubert, Claude Bernard and Jean Cayrol.

In addition to his research, Bertrand taught a variety of courses on French civilization, literature, art and language. He enjoyed exposing people to French culture and frequently accompanied students on trips to France with his wife and daughter as part of Stanford’s Bing Overseas Studies program in Paris.

“He loved teaching and finding new ways of thinking about Paris and French culture,” said Bertrand’s daughter, Ariane Bertrand.

Ariane credited her father for developing her own curiosity and drive in life.

“He instilled in me the importance of the love of learning and the joy of being fascinated by things and sharing them with people,” she said.

In his spare time, Bertrand gardened, listened to classical music and watched numerous French films, his family said.

Other Stanford professors who knew and worked with Bertrand described him as humorous and kind.

“Besides his great culture, his intellectual curiosity, his Gallic charm, Marc was quintessentially a French homme de gauche, generous and trustworthy,” said Ralph Hester, professor emeritus of French, who had known Bertrand since the 1960s. “He was a superb colleague, a confrère and a faithful friend.”

Richard Schupbach, professor emeritus of Slavic languages and literatures, said Bertrand seemed to always have the right word or phrase to say about a political event or a controversy, grounding it in context and poking fun of its seriousness.

“I just enjoyed talking to him,” Schupbach said. “He had such a wonderful sense of humor and this impeccable sense for the absurdity of life.”

To his students, Bertrand was known to use understatements when talking about other people’s work. He was especially renowned for saying pas mal, which means “not bad” in French. One day, a group of his students baked him a cake with that French phrase on top, his wife said.

“He was extremely enthusiastic about his students,” said Vida, who met Marc at Stanford, where she was a lecturer of French. “And the students would call him many years after he retired.”

Besides his passion for teaching and research, Bertrand was also devoted to his family, faithfully driving his grandson to soccer practices and his granddaughter to horseback riding. One time, he created a slideshow about French culture especially for them, his daughter said.

“He loved spending his time with his grandchildren,” said Ariane Bertrand. “He would always try to expose them to new things.”

Bertrand is survived by his wife, his daughter and his two grandchildren, Luc and Sophie.