The author Joseph Conrad insisted his work The Shadow-Line: A Confession was not a book about the supernatural. But sometimes the real can be spookier than the imagined, and what we observe outpaces our worst nightmares. So it is with Conrad’s late novella.

“The belief in a supernatural source of evil is not necessary; men alone are quite capable of every wickedness,” Conrad said a few years before World War I. Certainly the rest of the century bore out his conclusions.

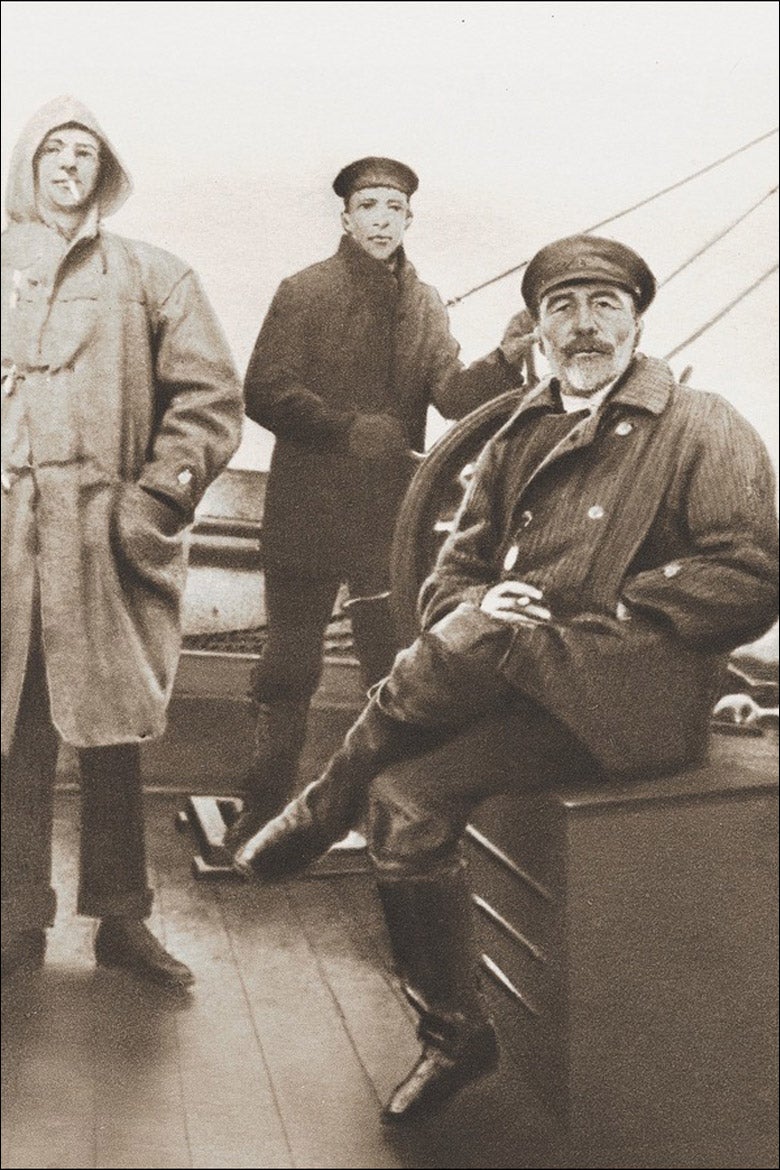

Joseph Conrad (foreground) on board the special service ship Ready in 1916. He wrote The Shadow-Line on his return from the voyage. (Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

The Another Look book club will discuss Conrad’s 1917 novella and the Polish author at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday, May 10, in the Bechtel Conference Room of Encina Hall. The Shadow-Line is available at Stanford Bookstore, Kepler’s in Menlo Park and Bell’s Books in Palo Alto.

The panel will be moderated by Another Look director Robert Pogue Harrison, an acclaimed author and professor of Italian literature. Harrison is a regular contributor to the New York Review of Books and the host for the popular radio talk show Entitled Opinions. He will be joined by drama Professor Rush Rehm, artistic director of the Stanford Repertory Theater, and Monika Greenleaf, associate professor of Slavic languages and literatures and of comparative literature.

The event is free and open to the public.

“I chose this short novel because of its exquisite prose and quintessentially Conradian drama,” Harrison said. “It probes the enigma of fate by putting circumstance, landscape and depth psychology into play all at the same time.”

He added, “Conrad is a master when it comes to putting his characters through trials. The Shadow-Line is one of the most intense of Conradian trials of character. It is not one of his best known novels and is certainly deserving of another look.”

Supernatural or not?

Conrad’s short masterpiece describes the “green sickness” of late youth, when a young man desires to “flee from the menace of emptiness.” The unnamed narrator’s flight ends when he is captain of a merchant ship in Southeast Asia; the terrors of sickness and the sea bring him to grief, maturity and wisdom.

In a two-page author’s note, Conrad denies the supernatural has anything to do with his story. We are meant, then, not to draw a line between the mate’s superstitious and feverish fear of his former captain, buried at sea, and the destruction of the ship to weather, wind and contagious fever. The mate says the ship will not have luck until it passes the spot where the reckless and demented captain was put overboard.

The Shadow-Line can also be read as a psychological study of the disintegration of an entire ship’s crew. That would be in keeping with Conrad’s worldview; he once called life a “mysterious arrangement of merciless logic for a futile purpose. The most you can hope from it is some knowledge of yourself – that comes too late – a crop of inextinguishable regrets.”

The year The Shadow-Line was published, The Argus praised the novel: “It holds the reader under a spell so strong that the book must be finished at one sitting, and even when it is laid aside it keeps its grip on the memory, and the impression left remains with a curious persistence.”

The Sunday Times wrote, in 1917, “Mr. Conrad is an expert in the business of suggesting mystery and the action of malevolent agencies and the endurance of a man under the buffets of fate. Not even Coleridge has held passers-by more spellbound under a tale of horrors on the ocean than does Mr. Conrad in this work.”

Origins of Conrad

Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski – Joseph Conrad – was born in 1857 in a largely Jewish village in territory that is now Ukraine; it had been part of the Polish-Lithuanian Respublica before partition, and at the time of his birth was part of the Russian Empire. His father was a Polish patriot and man of letters, and the family had a migratory existence. Conrad began a seafaring career as a teenager, and eventually joined the British merchant marine and became an English citizen.

He was one of the very few writers to establish his literary reputation in a foreign tongue. (Vladimir Nabokov comes to mind as well, but the author of Pale Fire and Lolita was reared in an aristocratic Russian family; however, he later claimed English was the first language he learned in his trilingual household.)

World War I was much on Conrad’s mind as he wrote Shadow-Land, and the book is dedicated to his son Borys, a soldier. By the time it was published, Borys had returned from the front, shell-shocked and gassed in the new technology of warfare. The war’s end would change forever the face of the Europe Conrad remembered.

Shortly after the war, a visitor to the Conrad household observed: “Conrad spoke fluently, but his accent, his manner of expression were such as I observed among the inhabitants of the south-eastern Polish borderlands. One felt clearly that when he thought of Poland, it was of a Poland of half-a-century ago. When I listened to him, I could not evade the impression that I am being carried back in time and talk to one of the people of long ago.”

Another Look is a seasonal book club that draws together Stanford’s top writers and scholars with distinguished figures from the Bay Area and beyond. The books selected are short masterpieces you may not have read before.

Media Contacts

Cynthia Haven, Another Look book club: cynthia.haven@stanford.edu

Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, cbparker@stanford.edu