|

See video and slideshow here.

May 13, 2015

Stanford students celebrate release of graphic novel American Heathen

The graphic novel, which Stanford students researched, wrote and illustrated, focuses on the life and times of a Chinese American man who dedicated much of his life to improving the lives of Chinese immigrants in 19th-century America. By Kathleen J. Sullivan

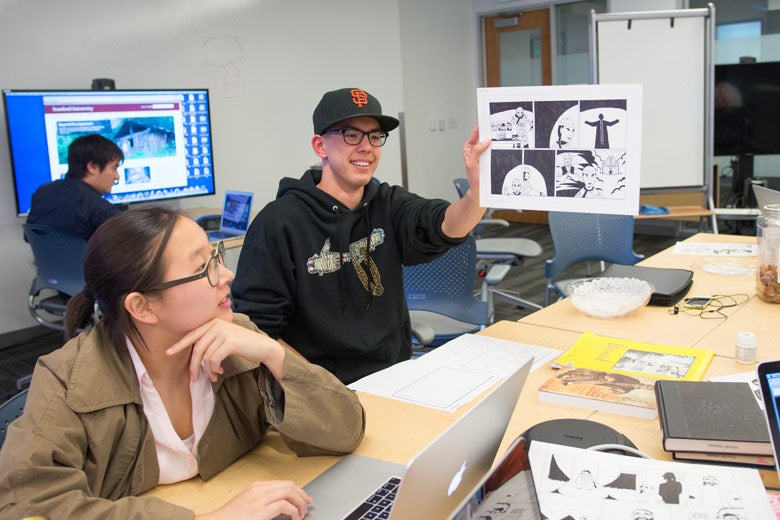

Sophomore Colin Kimzey, right, shows his completed drawing to junior Leah Kim during Stanford's Graphic Novel course. The final product, American Heathen, is now in print. (Photo: L.A. Cicero / Stanford News)

At a recent book launch on campus, six young Stanford artists sat at a long table in the Terrace Room of Margaret Jacks Hall with copies of American Heathen, the graphic novel they had written and illustrated, propped up in front of them.

The event marked the highly anticipated culmination of a two-quarter English course that began in September 2014, when the students met for the first time, and finished in March 2015, when they shipped their manuscript to the publisher.

It was the first time the students had seen their 160-page book about the life and times of Wong Chin Foo (1847-1898). Wong, an engaging speaker and a passionate advocate for the oppressed, dedicated much of his life to improving the station of Chinese immigrants living in 19th-century America.

One by one, the students stood up to talk about creating American Heathen, from choosing Wong as their subject through research, thumbnail sketches, drawing, inking and coloring, "cleaning" pages of stray marks, lettering, and editing.

Laura Zalles, a junior majoring in geology, talked about the importance of creating images that accurately reflected the historical period in which Wong lived. That required a lot of research into life in the late 1800s, not just in America but also in China.

In addition to reading a biography about Wong, the students researched clothing, sailing ships, slang, organized crime rings in American "Chinatowns," U.S. laws that denied civil rights to Chinese immigrants and civil war in South China.

In a couple instances, they discovered they hadn't done quite enough research.

"We had already finished inking a lot of pages and fully colored some pages when we learned that back in the century that we were trying to represent, everyone wore hats outside, all of the time," Zalles said, an insight into 19th-century America that also surprised the audience, which responded with sympathetic laughter.

"We had to go back through all of our pages that had people outside and photoshop in hats. But they had to be appropriate hats – hats that politicians and Chinese people in America actually wore in the 1880s."

Leah Kim, a junior majoring in computer science, talked about the "cool, creative process" of thumbnailing – producing pencil sketches of entire pages that would tell the dramatic story of Wong's life in a visually appealing way, including directions to artists about the emotions characters should convey. That was the first draft of the book.

"Thumbnailing sounds pretty easy, because you just need to draw what the page should look like – no details necessary," Kim said. "But we learned that it's quite difficult, because we had to present the story in a very condensed manner, and we needed to write down even the pettiest details on the side, just to make sure the final page would look exactly as we wanted. I would often ask the artists for more pages for certain chapters, because I didn't think there was enough visual information and dialogue that would help readers understand the story."

Naomi Lattanzi, a junior majoring in Japanese, described one of the challenges involved in writing a story set in an openly racist period in U.S. history.

"In order to show what our character was fighting against, we had to actually write in a lot of the grossly racist things that were said back then – without killing our own souls," she said. "Finding that balance was pretty interesting."

Visual thinking

The three instructors who had taught the course – a comics journalist and two fiction writers – stood on the sidelines at the book launch, beaming like proud parents, and took turns praising the students for their accomplishment.

While the six students at the table had done the lion's share of the artwork, seven of their classmates who took the first quarter of the course but were unable to take the second also are counted as authors of American Heathen.

"It's a heck of a thing to make a book, and even more of a heck of a thing to make a book as a team," Andy Warner, the course's art director, told the audience. "This group came together through thick and thin over the course of the two quarters and did it. And I'm incredibly proud of them."

During fall quarter, the students explored artistry and storytelling by studying several graphic novels, including Persepolis, a memoir about coming of age in Tehran during the Islamic Revolution, by Marjane Satrapi, and Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, a memoir about a father-daughter relationship, by Alison Bechdel.

"Part of teaching visual thinking and good artistic practice, no matter what the medium, is getting students to figure out why they like something," said Warner, who produces fiction, nonfiction and comics journalism.

"Most of the students who enrolled in the class were already well read in comics, so it was relatively easy to make the jump to talking critically about them. Once you're thinking about authorial intent, that awareness starts to creep into your own work. That's the most important first step. After that, it's all craft, which is a pretty straightforward thing to teach."

Don Le, an undeclared sophomore and one of the artists of American Heathen, most enjoyed "inking" the book – using a brush pen to draw individual pages on paperboard.

"Of all the pages I inked, I'm actually the most proud of the first one I drew for the book – the page where Wong gets pushed down the stairs," Le said, referring to a scene in which Chinese gangsters assault Wong in San Francisco's Chinatown. "I really like how he seems to pop out of the page, which gives the scene a sense of urgency as he tumbles down the frames of the page."

Long-form narrative

Scott Hutchins, a lecturer of fiction in the Creative Writing Program, said producing a graphic novel about Wong gave students the opportunity to create a sweeping tale of a historical figure – and the times in which he lived – for a broad audience.

A graphic novel, like a novel or a piece of narrative journalism, requires a plot or a structure, said Hutchins, author of the 2012 novel, A Working Theory of Love.

"It's hard to teach novel writing in the confines of a quarter system, since it takes years to write a novel," said Hutchins, who has co-taught the graphic novel course since 2012. "So I'm happy for the graphic novel course to be a class in which we can teach long-form narrative in a practical way."

American Heathen is the sixth graphic novel Stanford students have produced since the university's Creative Writing Program launched the course in 2008. An online version of American Heathen is available on its website.

Hutchins said the students chose an unconventional structure – moving backward and forward in time – that provided a poignant way to express Wong's story.

To help readers follow the time jumps, Grace Klein, an undeclared freshman, drew a timeline, which doubles as a table of contents. It appears at the beginning of each chapter with key scenes in pullout panels.

"The pullout panel for Chapter 2 is a composite of Wong holding out his arms like a cross as he gave his Why I Am a Heathen speech and the American flag, because he gets his citizenship in the book's second chapter," Klein said. "If you want to dig for symbolism, it juxtaposes his Chinese background with his American future."

Three weeks of editing

During a winter quarter session on editing led by Shimon Tanaka, a lecturer of fiction and creative nonfiction in the Creative Writing Program, students sat in a half circle around a large video screen scrutinizing each blown-up page – and finding things to fix, add or improve.

"We need to move down the speech bubble so it doesn't look like it's coming out of Wong's ear," one student said. "Wong is missing his hat on the page where he gives his Why I Am a Heathen speech," said another. "Let's add Chinese signs to the shops in the street scene," one student suggested.

Tanaka, who has co-taught the course since 2012, said one of the biggest challenges producing a graphic novel in only 20 weeks is that everyone is usually working right up until – and often past – deadline, leaving very little time for editing.

"These students rose to the challenge across the board, staying on schedule and even volunteering to take on extra work," he said. "This gave us nearly three weeks for editing, resulting in a more coherent, tighter book."

Tanaka also singled out the course's teaching assistant, Arielle Basich, a senior majoring in American studies, for praise. (Basich is one of the authors of A Place Among the Stars: Thirteen Women and Their Quest for Space, the 2014 book produced by students enrolled in the graphic novel course.)

"This is a project that requires students to be not just creative, but detail-oriented and organized as well," he said. "Hours can be spent coloring a beautiful page, but if the resulting computer file is mislabeled or put into the wrong digital folder, all that work can be for naught. In this respect, Arielle's organizational skills were an immense benefit to the project."

A flawed hero, a human story

Colin Kimzey, a sophomore majoring in product design, said that as the class delved more deeply into Wong's personal history, the students discovered sordid aspects of his life that were hard to square with their initial view of Wong as a civil rights leader.

They learned that Wong, who testified in Congress against extending the racist Geary Act of 1892, was prejudiced against Irish immigrants and Cantonese-speaking immigrants from South China. (Wong, who was from Shandong Province in North China, spoke Mandarin.) He was a showman who had profited by marketing silly aspects of Chinese culture to curious Americans. He had abandoned his wife and son in China.

Still, they decided that Wong's character flaws contributed to a compellingly human story, and did not diminish his great act of courage – challenging the oppressive status quo at a time when people like him faced systematic discrimination. Kimzey said the book is a nuanced portrait of a flawed yet charismatic man.

"One of the big forces behind the book is the fact that this is a largely untold story for a people whose history doesn't have many stories like this – activists fighting for civil rights at a time when racism was so powerful," Kimzey said.

Lattanzi, who has taken the graphic novel course two years in a row and is one of the authors of last year's A Place Among the Stars, decided to come to Stanford after hearing about the graphic novel course during Admit Weekend. Asked how she would pitch the class to prospective freshmen, Lattanzi said:

"I would tell them that as awesome as making stories on your own might be, it's even better to sit with a group of other people who have entirely different ways of thinking and carve out a story together. And afterward, you get a nifty printed book to show off to your friends and grandparents! I might also pull up the Tumblr I made for our novel, because I wouldn't want prospective freshmen to make the mistake of thinking that just because a class is work-heavy and based on a serious topic that you can't have fun with it."

-30-

|