|

View video here.

April 20, 2015

Stanford scholar reveals how fears of damnation undergird American history

Drawing on 18th-and 19th-century writings, religious studies scholar Kathryn Gin Lum shows how the concept of "hell" influenced religion, politics and social reform. By Marguerite Rigoglioso

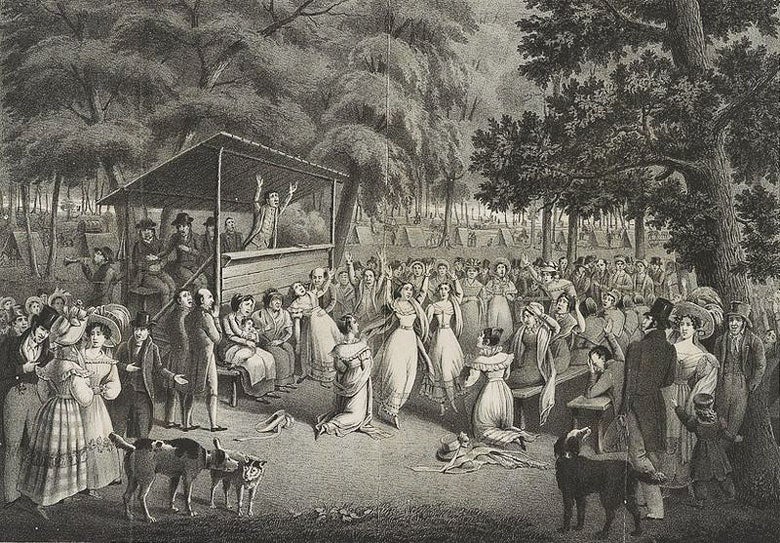

A drawing on stone ca. 1829 of a religious camp meeting. In a new book, religious studies scholar Kathryn Gin Lum analyzes how the belief in hell influenced Americans' perceptions of themselves and the rest of the world. (Image: H. Bridport/Wikimedia)

Early Americans were apparently not just concerned with life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. They were also obsessed with issues of hell and salvation.

In her recently published book, Damned Nation: Hell in America from the Revolution to Reconstruction, Kathryn Gin Lum, assistant professor of religious studies at Stanford, shows how hell was used as a tool of political motivation in the first century of nationhood.

Lum, who studies the intersections between religion and race in America, analyzes how the widespread belief in hell influenced Americans' perceptions of themselves and the rest of the world between the Revolution and Reconstruction.

Lum discovers that under the threat of political chaos and economic unease, "saved" and "damned" became distinctions as crucial as race, class and gender. These concepts influenced social reform efforts such as the temperance movement, missionizing and slavery reform.

"The prevalent belief that you might end up in eternal torment because you've gambled, danced or broken the Sabbath was a powerful ideology," says Lum. "It reassured anxious Americans that something was going to keep citizens in line in the new republic."

Although Lum's book focuses on the period up to the Civil War, when many worried about the eternal fate of themselves and their loved ones, her research is hardly describing a past that's long gone.

"Nearly 60 percent of Americans today say they believe in hell. It's not much talked about, but it still underlies the way many people behave, including how they vote, and how they view the world," says Lum.

She notes, for example, that every Halloween, some conservative evangelical churches across the United States sponsor "hell houses." Local teenagers and adults don costumes and demonic masks to enact "sins" that land a person in hell. Since the 1970s, such displays have operated to frighten teens away from abortion, homosexuality and recreational drugs.

"I think the 19th-century mentality that evangelical success was crucial for the survival of the young nation while its failure spelled the country's doom continues to be seen today," Lum explains. "Conservative evangelicals care a lot about issues like same-sex marriage and abortion because of the impulse that roots their own salvation in their ability to save others."

Justified by hell

To get at newly minted Americans' thoughts about hell long ago, Lum combed sermons, diaries, letters, newspapers and political tracts found in archives ranging from the Beinecke Library at Yale to the Hawaiian Mission Children's Society Library.

Her book explores the ideas of theological leaders such as Jonathan Edwards and Charles Finney, as well as those of ordinary women and men. She discusses the views of Native Americans, Americans of European and African descent, residents of Northern asylums for the insane and Southern plantations, New England clergy and missionaries overseas.

"People on both sides of the emancipation debate used the threat of hell to argue against each other," says Lum, who teaches intriguingly titled courses at Stanford such as Demons, Death and the Damned and Is Stanford a Religion? – along with classes on Asian American religions and race and religion in America.

According to Lum, the prevalent belief at the time that most of the world was damned could justify genocide and imperialism.

In examining diaries of people traveling the Overland Trail from the East to the West, for example, she found personal accounts detailing the opening of Native American graves and observers' opinions that their skulls were those of people who had no souls. "It was a horrifying application of the idea that some people are just not meant to be redeemed," she says.

Yet Lum is clear that her book is not meant to mock either the concept of hell or people who adhere to it.

"There are those who take it seriously and those who think it's ridiculous. I know good people on both sides, and the book is intended to include both of these voices," says Lum.

Curiosity about the afterlife

Lum's serious grappling with the "big questions" formally began with the sudden illness and death of her father when she was a 19-year-old undergraduate at Harvard.

"No one around me knew how to talk about death or what happened afterward, so I was driven to investigate it myself," says Lum, who decided to come home and finish her degree at Stanford, where she studied American history with an emphasis on religion.

After Stanford, she continued her studies at Yale, where she wrote the dissertation that has become her new book. Originally intending to write a history of the afterlife in America, she quickly realized she had to narrow her topic if she ever wanted to complete graduate school. She found that she was far more interested in what people thought about the dark side of the afterlife than the subject of heaven, with its "repeating motifs of pearly gates and streets of gold."

What has it been like to traverse the byroads of brimstone since 2005, when she first began the project at Yale? "It sounds like it would be depressing or morbid, and there's some of that, but mostly it's been exciting," says the scholar. "I find it an intriguing exploration of how people think they should be living."

Stepping up a few Dantean rungs for her next book, Lum is looking at the concept of the "heathen" in America.

"What interests me is how 'heathen' operates as a category of not just religious but also racial difference," she says. "For example, the term went from describing anyone who was not a member of a recognized major religious tradition to being associated particularly with the 'heathen Chinese' by the late 19th century. How did religious bigotry shade into racism?"

As to how her own personal beliefs have developed since the death of her father, Lum says, "I don't think death is the end of the line, but when I teach I don't come from any one perspective. Ultimately, I believe it's important that people come to their own conclusions."

Lum hopes that her book will get more people to think about the implications of holding a belief that those who do not follow one's faith will be damned. "How does it affect the way we live, treat others and see the rest of the world today?" she asks. "It's an important question in a pluralistic society and, more broadly, in a world in which religious tensions are running higher than ever."

For more news about the humanities at Stanford, visit the Human Experience.

-30-

|