|

March 4, 2014

Stanford scholar explores civil rights revolution's positive impact on the South's economy

Economic historian Gavin Wright's latest research illustrates how the civil rights revolution of the 1960s achieved something rarely seen in social revolutions: economic improvements that stimulated growth for an entire region. By Fabrice Palumbo-Liu

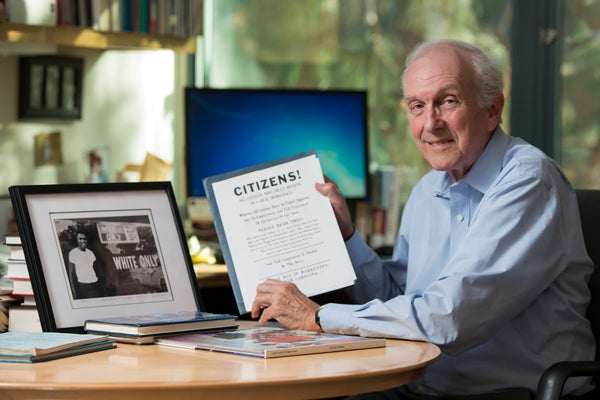

Professor Gavin Wright displays some of his collection of photographs and handbills from the civil rights era. (Linda A. Cicero / Stanford News Service)

America is in the midst of a sequence of golden anniversaries: the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

For Gavin Wright, a professor of American economic history at Stanford, this period also marks a half-century journey from young civil rights activist to leading authority on the economic history of the South.

Wright's interest in the economics of the civil rights movement began in 1963 when, as a college student from a Quaker family, he chose to participate in a voter rights education initiative organized by the Quaker organization American Friends Service Committee Citizen Education Project.

Wright and 13 other students spent the summer working with rural ministers and local citizens to present workshops designed to increase awareness of voter registration and civic activism among the residents of Warren County, North Carolina.

As Wright promoted desegregation and racial equality through discussions with black and white community members and business people, he was struck by how closely their economic goals were intertwined with racial goals: "Here we were, college students preaching tolerance and racial brotherhood, and very often [the response was] 'OK, but where's it going to get us economically?'"

Over time, as an economics graduate student and then as an interdisciplinary scholar, Wright became increasingly curious about the economic motivations driving each side of the civil rights struggle.

When mainstream economics failed to answer his questions, Wright began specializing in economic history, eventually becoming an expert on the antebellum slave economy and southern regional development.

Scholars frequently look to Wright's book Old South, New South as a definitive economic analysis of the South since the Civil War. Building on that work, Wright's latest research reveals how the civil rights confrontation achieved something seen in few other social revolutions: It benefited both sides economically.

Wright found ample evidence showing that rather than expanding the educational and economic opportunities of blacks at the expense of white access to the same resources, the civil rights movement yielded positive economic growth for both groups.

Wright emphasizes that racial equality was valued both as a matter of respect and human dignity and as an economic goal – a moral right empowered by material means. Segregated public accommodations, for example, were not only an attack on black self-respect; the issue also held real economic content, as black travelers could not rely on dining or a safe place to stay the night.

"Once the landmark federal legislation (of 1964 and 1965) was in place, a combination of pressures and incentives fostered new biracial coalitions in states and metropolitan areas that restarted the engines of the Southern growth machine," Wright wrote in his recently published book Sharing the Prize: The Economics of the Civil Rights Revolution in the American South.

Eliminating measures designed to marginalize black voters helped lead to 25 years of "vigorous two-party competition," Wright noted. During this period, civic participation soared and calls for education and economic development from across both aisles replaced the focus on segregation, with far-reaching boosts to per-pupil spending and the local economy as a result.

Obscure sources reveal unique story

Patiently working through a panoply of historical source materials – from Equal Employment Opportunity Commission reports and Federal Census data to FBI interviews, as well as Assistant U.S. Attorney General Burke Marshall's papers – Wright uncovered a unique economic story that often goes unnoticed in national data analyses of the movement's economic impact.

One of the more obscure sources that Wright found to be quite valuable was the Federal Reserve's monthly index of retail sales.

"[The index] came in for quite a bit of attention during times of crisis in Southern communities, where the boycotts and sit-ins were cutting into business, and they were pointing to these kinds of sales figures for either positive or negative evidence," Wright said.

Wright's understanding of the region and ongoing research bolster his argument that underreported economic accomplishments of the civil rights movement resulted in several advantages for the Southern economy on the whole.

"People work with national data but often don't look at the regional component – when they do, they almost always find that it makes a big difference," said Wright.

As one example, once the region acquiesced on school desegregation in the late 1960s, Southern schools became the most racially integrated in the nation. Despite the long history of resistance and evasion, longitudinal studies now report significant long-term economic gains for African Americans in the South.

In addition to improving black students' prospects for a wider range of employment (as more workplaces became desegregated), desegregation did not harm white students' academic performance; their test scores continued to move upward toward the national average, Wright's data show.

Wright views the role of economic history within economics as "a kind of institutionalized insurgency." He stresses the importance of historical context for the operation of economic processes and policies.

Economic history in the making

Following what he calls the "Civil Rights Revolution" of the 1960s, Wright found that the South actually took the lead in numerous paths toward integration, which in turn improved its economy in both sudden and lasting ways.

A comparison of median black male incomes by region between 1953 and 2001 shows that Southern incomes accelerated sharply during the mid-'60s and steadily increased thereafter, in contrast with their Midwestern and Northern counterparts.

Wright finds further support in the desegregation of the Southern textile industry which, following the Civil Rights Act, opened up a number of better-paying positions for black employees without reducing white labor.

Opposing the view that textile jobs were desegregated only because the industry was dying, Wright argues that between the 1960s and 1990s, the textile industry offered "a path out of poverty for an important generation."

With increases in black incomes and occupational status came enhanced revenue from both inside the local area and outside government, as opposed to a dependence on regressive local sales taxes.

As the outcomes of the movement created more economic possibilities within the Southern states than ever before, black migration from the region tellingly reversed its half-century course: Wright estimates that approximately 2 million African Americans have moved to the South since 1970.

Acknowledging that many political and economic gains are now in jeopardy, Wright argues that there are still valuable lessons to be learned from the historical experience of the civil rights movement.

The economic historian, Wright says, must hold up "powerful historical examples where you show that history has a bite, that history mattered, that the outcome was not the inevitable result of some deep economic forces."

Fabrice Palumbo-Liu writes about the humanities at Stanford.

-30-

|