|

View video here.

February 3, 2014

Stanford professor traces roots of the psychedelic '60s to postwar America

New research by cultural history expert Fred Turner reveals how changing ideals about American democracy in the 1940s and '50s planted the seeds of rebellion that flowered in the counterculture of the 1960s. By Tom Winterbottom

In a new book, cultural history expert Fred Turner investigates the surprising historical origins of the psychedelic counterculture.

Fred Turner, associate professor of communication, has one overriding humanistic desire in his work: "My deepest ambition is to create ways in which people can peer in and see the historical conditions in which they are living their lives."

A scholar of media, technology and American cultural history, Turner has shown how technology interacts with existing cultural and social practices to shape what we do in our daily lives.

That passion led him to investigate the roots of the 1960s counterculture, which is generally understood as a spontaneous rebellion against the stiff conservatism of the postwar period.

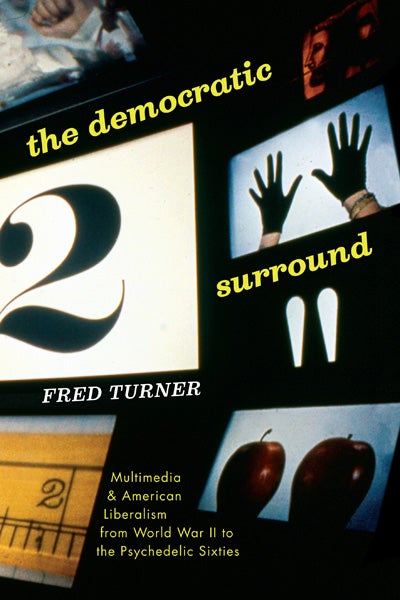

Not so, says Turner, whose latest book, The Democratic Surround: Multimedia and American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties, investigates the surprising historical origins of the psychedelic counterculture.

"What I found is that the counterculture owes many of its ideals, and particularly its understanding of how media shapes people, to a generation earlier that really came to life during World War II. This is a unique and astonishing find."

By studying materials in more than a dozen archives, including the National Archives in Maryland and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Turner learned that 1940s and 1950s American liberalism offered a far more radical social vision than we now remember.

"During the early Cold War period, there was an extraordinary turn toward explicitly democratic, open and inclusive ideas of communication and with them new, flexible models of social order," Turner said.

In government policy statements, correspondence between artists and politicians, and even in course syllabi by influential Bauhaus artists, Turner found that 1960s thought was deeply influenced by these earlier ideas.

He shows that the earlier cultural shift, in the 1940s and 1950s, provided the basis for the revolutionary and wild-eyed individualism of the 1960s counterculture.

Whereas 1950s America has typically been remembered for McCarthy and the Korean War, Turner's findings completely redefine our view of this period and its indelible impact on the American psyche.

"In the '60s psychedelic counterculture boomed. People surrounded themselves with psychedelic media – videos, art, installations – thinking that it would turn them into a different kind of person, perhaps make them more personally satisfied and psychologically fulfilled," Turner said.

Culturally and ideologically, he says, much of this came from the previous decades and was not a spontaneous countercultural emergence.

"I was always told that the 1960s were a rebellion against the 1940s and 1950s, but that turns out to be far from the truth," Turner said.

'The Democratic Surround'

Turner, whose previous works have explored American cultural memory and cyberculture, found himself immersed in the works of German psychoanalyst Erich Fromm, American anthropologist Margaret Mead, English anthropologist Gregory Bateson and American mathematician Norbert Wiener as he delved into his investigation.

These figures, it turns out, were among the founders of an eclectic group of 60 of America's leading social and psychological scientists who theorized two things: the "democratic personality," and the development of media environments.

"In the 1940s, a group under the rubric of the Committee for National Morale convened in New York, led by Arthur Upham Pope, an art historian, and they became incredibly influential," Turner said.

He says that the democratic personality they promoted – opposed to fascism and, later, communism – was defined as being open, flexible, and able to integrate diverse experiences and to collaborate and coordinate with others.

In the same period, Bauhaus artists, commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, helped create American propaganda exhibits that could convey the Committee's idea of a democratic personality in American society.

At the Museum of Modern Art, for example, the Bauhaus artists created propaganda exhibitions that surrounded viewers with images, from above and below, and asked them to make sense of them in their own individual ways, as free, democratic individuals.

These multiscreen and multimedia environments would become a hallmark of psychedelic culture a decade later.

"The postwar foundation for democracy was built on Bauhaus aesthetics combined with social and psychological theorists working on the democratic personality," Turner said.

These two streams, he says, flowed together for 30 years and went in two directions.

"On the one hand, there is the propaganda throughout the Cold War," Turner said. "On the other, the movement developed culturally through the artists to Black Mountain College, John Cage and the counterculture of the 1960s.

"The children of the 1960s not only overthrew their parents' expectations but they also fulfilled them. They used multimedia environments to become the free individuals that Margaret Mead and the Committee for National Morale were calling for decades earlier."

From counterculture to cyberculture

Although Turner sees the democratic vision and the desire for integration and community of the 1960s underlying digital media today, he notes that few people are thinking about the significance of culture and aesthetics in shaping our tech-driven culture.

"Current trends toward entrepreneurship and resisting hierarchy, as well as the desire to create egalitarian work spaces, are nothing new," said Turner. "It is a rhetoric that comes right out of the 1940s."

As director of Stanford's Program in Science, Technology and Society (STS), Turner is showing students the value of understanding the potential societal and cultural impact of technological change.

Popular with a wide range of undergraduates, STS focuses on this interaction and has boomed in the past three years to become one of the leading majors on campus. It is the only major to offer both a BA and a BS degree.

"STS is a liberal arts major for an era suffused with science and technology. To be a good humanist now, you have to engage with current science and technology, much as one had to in the Middle Ages and in the Enlightenment," he said.

In STS, students essentially take two-thirds of a humanistic or social science major and two-thirds of a science or engineering major. English and computer science is one of the most frequent combinations.

"Humanities is a field willing to ask questions such as how should we live, and what's the right thing to do," Turner said.

"It's hard to keep track of how these moments in which we live have been shaped by others in the past. Of course, I want people to 'Be Here Now,' but I also want them to know how they got here."

Tom Winterbottom is a doctoral candidate in Iberian and Latin American cultures at Stanford. For more news about the humanities at Stanford, visit the Human Experience.

-30-

|