|

January 29, 2014

Stanford author meshes text and tech

In his fiction and his classroom, novelist Scott Hutchins sees Silicon Valley tech culture as a vehicle for exploring the human condition. By Justin Tackett

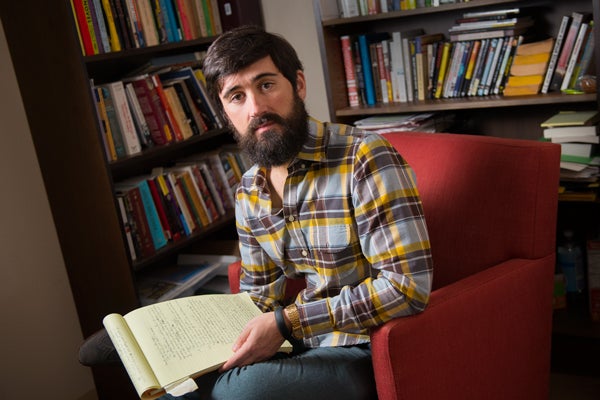

Author Scott Hutchins, a former Stegner fellow and lecturer in Creative Writing, incorporates high technology into his fiction but wrote his latest novel by hand on a yellow pad. (Linda A. Cicero / Stanford News Service)

Like many novelists, Scott Hutchins writes about traditional literary themes like love and family, drawing from a wealth of personal experience. Unlike many novelists, however, he also finds inspiration in the cutting-edge world of artificial intelligence (AI).

A former Stegner Fellow and current Jones Lecturer in Stanford's Creative Writing Program, Hutchins published his debut novel, A Working Theory of Love, in October 2012. Set in San Francisco, it's "essentially about relationships," he said, exploring divorce, bachelorhood and even suicide.

Central to the novel is protagonist Neill Bassett Jr.'s relationship with his father, Dr. Bassett. Neill cracks jokes, discusses health concerns and occasionally tackles politics with his father. But there's a twist.

Neill's father is dead, and Neill is talking to a computer.

The 30-something divorcee is trying to program the world's first sentient computer for a fictional tech company using the journals of his deceased father to construct the computer's thought-process.

"I was attempting to write a novel around a talking computer," Hutchins says. "I didn't know if I could get away with it. I kept thinking, 'This is ludicrous. No one will accept this.'"

But Hutchins wanted to write a "novel of ideas" and ask the big questions, like what it means to be human. "It turns out that artificial intelligence is exceptionally good at investigating these questions," he said.

"Plus, I was doing more and more talking to my own computer – my social life and work life were increasingly morphing into online phenomena. The old philosophical puzzle – how do you know if someone is a real person or just an automaton duping you into thinking it's a real person – began to feel like the most pressing question of my daily life."

Just as Neill uses his father's journals as the basis for constructing his sentient computer, Hutchins used himself as the basis for Neill and other characters. Hutchins and his protagonist, for example, were both raised in Arkansas and now live in the Bay Area. "I drew on my bio in many ways," Hutchins said. "There's a little bit of me in every character."

Being at Stanford has intensified Hutchins' research and interest in exploring technology through fiction.

"It's amazing being here with an awareness of what computer scientists are doing currently," he said. "I'm able to just send them an email and have lunch."

Where AI isn't science fiction

He cites, for example, the thinking of the late John McCarthy, the Stanford professor who minted the term "artificial intelligence" and founded the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, as an influence on his writing.

"It's exciting to write about these topics in Silicon Valley where AI is not science fiction," he said.

Stanford will feature prominently in Hutchins' second novel, which he is working on now. He won't divulge many details, but did say that he will once again explore scientific themes.

Hutchins believes literature and science have much to tell each other. "In the end, writing is about possibilities. We should be thinking hard about what our actual experience is going to be with these technologies. Creative writing is in a unique position to do that."

Hutchins' endeavor to write great fiction revealed itself to have more and more in common with the ongoing attempt to develop AI in computer science circles. For AI developers, the Holy Grail has traditionally been the radically positivist Turing Test, theorized by British mathematician Alan Turing.

"It's a very empirical approach to machine intelligence," Hutchins explained. "The Turing Test basically says that if a computer, during a conversation, can make us believe we're dealing with a human, then we must conclude the computer is intelligent."

This suspension of disbelief – the illusion that you are encountering another person when, in fact, no person is present – is also central to fiction, Hutchins observed, in which a major goal of the novelist is to create believable characters.

"There's an inherently fictional quality to projecting personalities onto machines. So while writing the book, I found myself involved in a meta-fiction – I was inventing a character who spends most of the novel inventing his father."

Hutchins' increasing interest in the Turing Test led him to contact the New York City-based Loebner Prize, an annual Turing Test that pits computer programs from around the world against each other. The founder, Hugh Loebner, promptly invited him to be a judge.

"I was particularly excited because I had been playing around with programming my own talking computer using A.I.M.L., a language developed by Rich Wallace, three-time winner of the Loebner Prize," Hutchins said.

Hutchins put the judging experience to good use. "A lot of the phraseology that the 'botmasters' used ended up in my book. There's the old trick from ELIZA, for example, where you send back all your interlocutor's statements as questions," Hutchins explains, citing one of the earliest "chatterbots," developed at MIT in the 1960s. "It might respond to 'I feel lousy today' with 'Why do you think you feel lousy today?'"

Robotic voice

Although there's no actual speaking in the novel between Neill and his computer-simulated father, Hutchins had to figure out how to portray the dialogue at readings. "When I read the lines myself, it didn't sound like the tonal flatness we often imagine from text output." Hutchins rigged his laptop to read lines out loud when prompted.

The trick, Hutchins discovered, was to use an artificial robotic voice.

If a computer's voice gets too close to sounding human, a phenomenon known as the "uncanny valley" happens, where most people find themselves innately repulsed, a possibly biological response to a psychological impostor. Like HAL, the rogue computer in 2001: A Space Odyssey, such voices "creep people out," Hutchins said.

But Hutchins said it was not particularly awkward to include a robotic voice in his readings, one of which he did at the Stanford-sponsored Litquake event this past fall. "We now talk to computers all the time," Hutchins said, noting that while he was writing his novel, technologies like Siri emerged and altered our interaction with our devices.

Hutchins enthusiastically brings communication technology into the classroom as well. Last year, he designed a course called "Twitter Fiction/Future Forms" in which students were challenged with the task of generating new modes of fiction through media like Twitter. "The results were fascinating," Hutchins said.

In winter quarter, he's teaching "Planning Your Novel: Starting from Scratch," a MOOC-like course with former Stegner Fellow Malena Watrous, through Stanford Continuing Studies. "The course won't be taught in the conventional sense, but curated," he said. "It's an experiment!"

Justin Tackett is a doctoral candidate in English at Stanford. For more news about the humanities at Stanford, visit the Human Experience.

-30-

|