|

January 17, 2014

Stanford Professor Elliot Eisner, champion of arts education, dead at 80

Eisner argued that a curriculum that includes music, dance and art is essential in developing critical thinking skills in children. By Brooke Donald

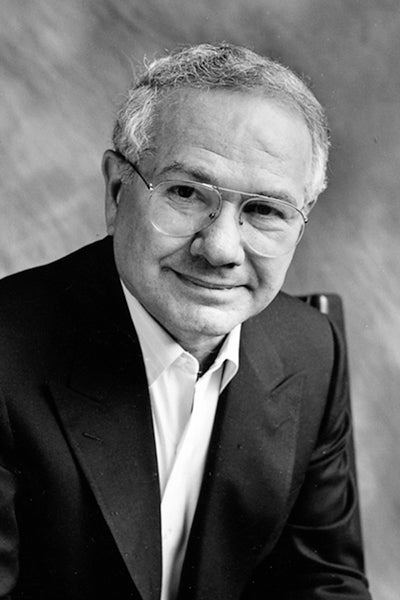

Elliot Eisner promoted ways that the arts could benefit student learning and educational practice. (Photo: Stanford Graduate School of Education)

Elliot Eisner, a leading scholar of arts education who presented a rich and powerful alternative vision to the devastating cuts made to the arts in U.S. schools in recent decades, died on Jan. 10 at his home on the Stanford University campus, from complications related to Parkinson's disease. He was 80.

Over the course of his academic career, Eisner, the Lee Jacks Professor of Education, Emeritus, at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and professor emeritus of art, championed ways that the arts could benefit student learning, as well as educational practice.

He maintained that the arts are critically important to the development of thinking skills in children and that the arts might offer teachers both a powerful guide and critical tool in their practice. He wrote 17 books and dozens of papers addressing curriculum, aesthetic intelligence, teaching, learning and qualitative measurement, in addition to his frequent and entertaining lectures throughout the nation and abroad.

Eisner's ideas reached beyond academia into the classroom: The National Art Education Association, of which he served as president, turned his list – "10 Lessons the Arts Teach" – into a poster, which can still be found today hanging on school walls nationwide. Among the lessons: The arts teach students that small differences can have large effects; the arts celebrate multiple perspectives; and the arts teach children that in complex forms of problem solving, purposes are seldom fixed but change with circumstance and opportunity.

"To neglect the contribution of the arts in education, either through inadequate time, resources or poorly trained teachers, is to deny children access to one of the most stunning aspects of their culture and one of the most potent means for developing their minds," Eisner wrote.

Eisner eschewed the more popular argument for the arts – that some research showed that instruction in music, dance and painting actually boosted test scores in math and science.

Eisner, rather, talked about art for art's sake.

"He figured out that there was something missing from mainstream educational theory and method," said his friend and Stanford colleague Professor Raymond McDermott. "He wanted to address matters of the heart, whereas most of the discipline was pushing a more mechanical view of the child and the act of teaching or researching."

Eisner reached into areas that sat on the margins of educational discourse: arts education, most literally; the art of education, by extension; and the art of researching education, most controversially, McDermott said.

"He moved these concerns to the front and center," McDermott said.

Eisner's unrelenting advocacy of the arts continued during periods in which arts programs were cut in schools, and a chorus of administrators and policymakers, faced with budget constraints, focused on test scores and worried that spending time painting or drawing was not academic enough.

"One of the casualties of our preoccupation with test scores is the presence – or should I say the absence – of arts in our schools," he wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 2005. "When they do appear they are usually treated as ornamental rather than substantive aspects of our children's school experience. The arts are considered nice but not necessary."

Eisner advocated a strict, more sophisticated and rigorous arts curriculum that would put arts instruction on par with lessons in reading, science and math.

Eisner was born in Chicago on March 10, 1933. From an early age, he was set on pursuing a career as an artist. He graduated in 1954 from Roosevelt University in Chicago with a BA in art and education and the following year received an MS in art education from the Illinois Institute of Technology. He then spent two years as a high school art teacher and discovered that he was more interested in the students than the actual art they were making.

Returning to graduate school in the late 1950s, he received a master's degree and doctorate in education from the University of Chicago. Eisner served as an assistant professor there before joining the Stanford faculty in 1965.

Along with his lectures, writings and teaching, his involvement in such curriculum initiatives as the Kettering Project at Stanford in the late 1960s and the Getty Center for Education in the Arts in the 1980s brought him wide recognition, helping him become an influential voice for teachers, scholars and other educators.

Eisner proposed that the forms of thinking needed to create artistic work were relevant to all aspects of education. Incorporating methods from the arts into teaching of all subjects would cultivate a richer educational experience, he said.

"The arts are fundamental resources through which the world is viewed, meaning is created and the mind developed," he wrote.

His work with the Getty Center advanced what is called Discipline-Based Art Education (DBAE). The curriculum structure advocated in DBAE stresses four aspects of the arts: making it, appreciating it, understanding it and making judgments about it.

This type of arts education, Eisner argued, would result in children better understanding the relationships between culture and art and becoming more artistically literate. He also believed children's conceptions of what knowledge is would be more sophisticated after this type of inquiry.

"His voice for evaluating teaching and student learning through many means, not just standardized testing, continued to be heard during the past three decades of standards-based school reform, testing and accountability," said Larry Cuban, professor emeritus of education at Stanford. "Eisner's eloquence in writing and speech gave heart to and bolstered many educators who felt that the humanities, qualitative approaches to evaluation and artistic criticism had been hijacked by those who wanted only numbers as a sign of effectiveness."

For his achievements, Eisner was honored with the Palmer O. Johnson Memorial Award from the American Educational Research Association, a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, a Fulbright Fellowship, the Jose Vasconcelos Award from the World Cultural Council, the Harold W. McGraw Jr. Prize in Education from the McGraw-Hill Research Foundation, the Brock International Prize in Education, the University of Louisville Grawemeyer Award for Education and five honorary degrees. He served as president of the International Society for Education Through Art, the American Educational Research Association and the John Dewey Society. He was a member of the Royal Society of Arts in the United Kingdom, the Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters and, in the United States, the National Academy of Education.

Former Graduate School of Education Dean Rich Shavelson described Eisner as a renaissance man.

"He had big ideas and he could communicate those ideas. He was often a lone voice in the wilderness, debating, sharing. He argued cogently and forcefully and challenged existing ideas at every chance," Shavelson said.

"He saw art in everything," said his daughter, Linda Eislund. "He wanted people to think critically about things, ask questions, learn with all their senses."

Added his son, Steve Eisner, a Stanford alum and the university's director of export compliance and export control officer: "He saw the arts as a way to help individuals realize their potential. He was extremely dedicated to his students and their understanding of how the arts can influence cognition and creativity. He saw them as a way to continue his life's passion, namely, advocacy for the arts."

In addition to his son and daughter, Eisner is survived by his wife of 57 years, Ellie; son-in-law, Eric Eislund; and grandsons Seth and Drew Eislund and Ari Eisner.

In lieu of flowers, the family requests donations to the National Art Education Association's Elliot Eisner Lifetime Achievement Award, established by the Eisners to recognize individuals in art education whose career contributions have benefited the field. The address for the NAEA is 1806 Robert Fulton Dr., Suite 300, Reston, VA 20191.

Contributions will also be gratefully received for the Parkinson's Disease Caregiver Program, Department of Neurology, Stanford University Medical Center, 3172 Porter Dr., Suite 210, Palo Alto, CA 94304.

A memorial tribute will be planned by the Graduate School of Education in the near future. The American Educational Research Association is planning a memorial symposium at its annual meeting April 3-7 in Philadelphia. There will be no funeral.

Memories and condolences can be shared at https://ed.stanford.edu/news/elliot-eisner-champion-arts-education-dead-80.

Brooke Donald is communications manager at the Graduate School of Education.

-30-

|