|

June 30, 2014

Language can help the elderly cope with the challenges of aging, says Stanford professor

By examining conversations of elderly Japanese women, linguist Yoshiko Matsumoto uncovers language techniques that help people move past traumatic events and regain a sense of normalcy. By Corrie Goldman

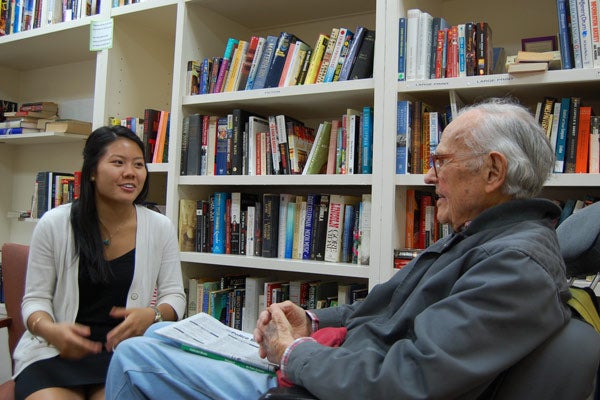

Freshman Giselle Tran interviews retired physicist William Frye for Professor Yoshiko Matsumoto's course on the joys and pains of growing older. Linguist Matsumoto studies how language helps the elderly cope with the challenges of aging. (Photo: Corrie Goldman)

Aging inevitably brings with it a variety of challenges: declining health, changes in work status, the loss of family and friends.

But in studying the conversations of older people, Stanford linguist Yoshiko Matsumoto discovered "common communication strategies of the elderly that may help them return to their happier, normal lives after experiencing hardship."

A professor of Japanese language and linguistics, Matsumoto through her research not only confirms how certain types of conversation contribute to a sense of well-being, but also offers older people, their families and caregivers potential tools for building resiliency following change.

Matsumoto's most recent work specifically focuses on older women's discourse about the illness or death of their husbands, with particular attention to conversations that also include humor and laughter. "These instances are not uncommon in my data, although they are a surprising combination," Matsumoto says.

Although there have been numerous suggestions about the positive effects of humor and laughter in difficult times, Matsumoto says the actual process of how that is accomplished through verbal interaction is not well understood.

Matsumoto's linguistic analyses of more than 60 hours of recorded conversations illustrate that there is in fact a structure to such discourse. Her findings suggest that by reframing a serious story through an ordinary, or "quotidian," perspective, the women she studied infused their dialogue with cathartic smiles.

When the death of a husband was discussed only as a life-altering event, there was no humor in the conversation. But some speakers reframed similarly painful events with strategic uses of humor and laughter in conversations with friends and acquaintances.

In one instance, a woman jokingly described how she used to chide her husband about his smoking and drinking habits – the very cause of his death. Matsumoto notes that by shifting the narrative perspective from somber to the ordinary, the speaker helped everyone involved regain the feeling of normality.

"Quotidian reframing," as Matsumoto calls the technique, "can function as a useful discourse strategy to relieve tension and let the participants regain the feeling or identity that they consider normal.

The power of the quotidian

Matsumoto conducted her fieldwork in Japan, a country with the world's highest life expectancy and the fastest growing elderly population. It is also where Matsumoto grew up and where her mother, now 84, lives, which gave Matsumoto access to a rich network of groups of elderly women.

Over the course of six months, Matsumoto collected conversations between elderly Japanese women and their friends as they ate, met, worked and socialized in the daily course of their lives. She also interviewed some women and recorded conversations at organizations that facilitate activities for the elderly.

In a detailed study of the recordings, Matsumoto searched for linguistic patterns, finding that a speaker's ability to situate a traumatic event in the context of everyday life experience "seems to be quite effective as a means of emotion regulation."

In one exchange, for example, Matsumoto observed that when a recent widow was calmly recounting her husband's death, she suddenly became animated in describing one of her visits to see him in the hospital. The widow "complained, half laughingly, that her husband told her to shush up when she tried to talk to him, saying he was trying to sleep and she was being too noisy," Matsumoto said.

The widow laughed as she recalled this "ordinary moment" that reminded her of her husband's perpetual complaining during their long relationship.

"By aligning one's identity with that of one's quotidian self through reframing," Matsumoto says, the speaker may "display his or her emotional stability, manipulate the tone of the conversation, manipulate one's self-image, or enhance rapport between the speaker and the listener/audience."

According to Matsumoto, "The quotidian perspective and the quotidian representation of self become important when the situation you are in or the memory you are recounting are extraordinary and psychologically intense."

"This," Matsumoto asserts, "is the power of the quotidian."

One of the most significant things Matsumoto says she discovered is the complexity of emotions and multiple identities that are expressed in casual conversations, which she notes is in "sharp contrast to the findings of previous studies, which were conducted in more controlled, and controlling, environments and in which the identity of the aged seemed more constrained and grim."

New perspectives on aging

Matsumoto notes that although the importance of inter-generational communication is known, her research also illustrates how crucial it is for older people to have casual conversations with people in the same stage of life. Some topics are more difficult to discuss with younger people, a fact that Matsumoto says explains why "older people can feel marginalized in their family conversations."

"As with everyone else, older people need friends," Matsumoto says.

Matsumoto's findings have applications for elder care, where, she says, caregivers can provide environments and space for older adults to casually speak with friends and peers, as opposed to psychotherapy or group therapy.

Caregivers can also create scenarios in which seniors benefit from quotidian reframing by doing away with the "rigid division of caregiver and care recipient" and instead "look for ways to play other roles than those institutionally defined, such as a daughter, a friend or someone who shares the same hobby or interests," Matsumoto suggests.

Making a related point, Matsumoto stresses the importance of "remaining aware that each older person has a continuous personal history" and that "reference to this history may be appreciated by the care recipients, as that would help them to realign themselves with their familiar identity."

Beyond the conversational data previously collected in Japan, Matsumoto will be expanding her examination of quotidian reframing with a cross-cultural comparison between older American women and her Japanese findings. She also plans to extend her research to other conversational narratives of psychologically intense events, such as the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake (March 11, 2011), where she says preliminary observations already suggest that quotidian reframing is used as a mechanism for coping with trauma.

Connecting the generations

Linguistics is one of numerous disciplines that students in Matsumoto's introductory seminar Joys and Pains of Growing Up and Older in Japan study to better appreciate the challenges and pleasures of being a senior citizen, in Japan and other countries.

Through an examination of recent research on aging from fields such as psychology and gerontology, as well as readings of firsthand narrative accounts written by seniors, Matsumoto wants her students to abandon negative stereotypes about the elderly.

At a time when societies across the globe are becoming more sensitive to discrimination, Matsumoto says it's important for students to comprehend that ageism is also a form of prejudice.

Caregivers, young people and even researchers sometimes "project their own understandings and preconceived notions" about aging onto the elderly, says Matsumoto.

For their final project, students are paired with a "senior partner" from the local community. The students record or videotape one or two informal conversations with their partner, which they then edit into narratives about their partner's life.

The goal of the final project, Matsumoto says, is to help students understand the lives of people who are much older than they are and to see that the young and the old face similar challenges of uncertainty and changing identities.

Freshman Giselle Tran met twice with retired physicist William Frye. Tran said Frye shared detailed accounts of his life experiences, which span both World Wars and the Great Depression. "We also discussed why he prefers to live alone, rather than with his children or in a retirement home, as well as his greatest fears and the changes he has experienced while aging," Tran said.

Tran, who expects to pursue a degree in economics and mathematical and computational science, said she "got a sense that the older generation is not completely separate from the rest of society and should not be treated as such. They are not generally as despondent or depressed as the media makes them out to be. They have had amazing experiences that they want to share with others."

For more news about the humanities at Stanford, visit the Stanford Humanities Center, home of the Human Experience.

-30-

|