|

March 8, 2013

Stanford economist learns lessons from yesterday's immigrants

Norwegian and U.S. census records provide a snapshot of 19th-century immigration, when poor, unskilled workers migrated to America en masse in an age of open borders. By Paul Gabrielsen

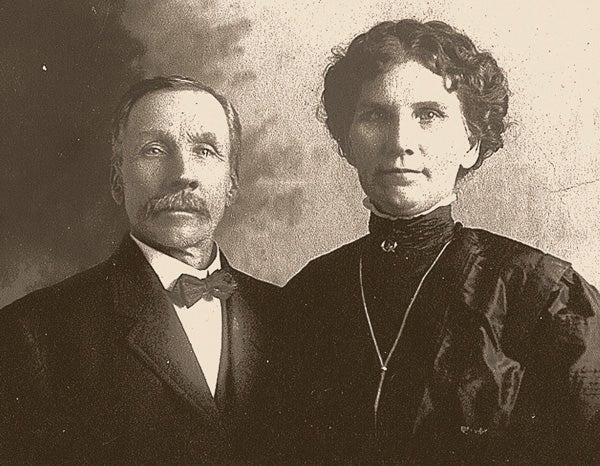

Hans and Pauline Gabrielsen, the ancestors of Paul Gabrielsen, the writer of the story. Hans Gabrielsen was among the 50,000 Norwegian men who came to the U.S. in the late 19th century when immigrants faced few restrictions, according to research by Stanford economist Ran Abramitzky. (Photo courtesy of Paul Gabrielsen)

Poor, unskilled workers were most likely to migrate to America's open borders in the late 19th century, says economic historian Ran Abramitzky, who tracked the migration of Norwegian men to America using census records. His research will be published in an upcoming issue of the Journal of Development Economics.

Each of the 50,000 men in Abramitzky's data set has a story, including Hans Gabrielsen, a 32-year-old sailor who in 1880 packed his bags and left his home in Hurum, Norway, to set sail for America. He entered the United States with considerably less difficulty than he would have today.

Ellis Island wouldn't open for another 12 years, and early immigration laws were still decades away. Hans came to America during a time of unrestricted immigration. With few exceptions, America's ports welcomed any healthy arrivals.

"No visas," Abramitzky said. "No green cards."

Hans Gabrielsen is the great-great-grandfather of the writer of this article.

Between 1850 and 1913, an era dubbed the "Age of Mass Migration," the United States accepted 30 million immigrants, mostly from Europe. By 1910, Abramitzky said, more than 20 percent of the workers in America were foreign born. Many native-born Americans saw these new arrivals as economic and cultural threats, eventually leading to immigration quotas and today's tough border policies.

Abramitzky, who studies the economics of migration, wondered how economic status in their home countries influenced immigrants' decision to move.

Since Norway kept thorough census records during the late 19th century, Abramitzky and his colleagues Leah Boustan and Katherine Eriksson, both at UCLA, focused on Norwegian migrants. The researchers, using the genealogy websites Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org to search digitized census records, attempted to match individuals in the 1865 Norwegian census to those in the 1900 census, in both the United States and Norway. They were able to match about 25 percent of the names, a typical rate for this type of study.

Census records contain information about the migrants' siblings and their parents' occupations. For example, Hans Gabrielsen appears in the 1865 census as an 18-year-old matros, or sailor, living with his parents and older brother. His father is listed as a farmer, living on rented land.

Abramitzky found that unskilled workers from poorer families were more likely to migrate. Oldest sons, anticipating inheriting the family farm, were less likely to migrate. Younger brothers, like Hans, were more likely to instead seek their fortune in America.

"Migration was seen as a substitute for inheriting wealth," Abramitzky said.

Today, Abramitzky said, immigration policies place more financial barriers before prospective migrants, pricing out many of the poor workers of Hans Gabrielsen's day. Today's legal immigrants are more likely to be well educated or highly skilled.

Differing views of immigration policies arise from different political perspectives.

"If you take a global perspective, and you want the poor people of the world to be able to make economic progress, then you want to allow poor people to migrate in large numbers," Abramitzky said. "If you're the U.S., it's a bit more complex."

Abramitzky's research supports the "Roy model" of migration. Proposed in 1951, the model predicts that poor, unskilled workers will leave a country where skills are valued for a country with more economic opportunity. During the Age of Mass Migration, unskilled workers could expect more upward mobility in the United States than in Norway.

Abramitzky, an Israeli who lives in the United States, said he empathized with the people he studied. Both countries he's lived in are nations of immigrants, making this a topic close to his heart.

Now Abramitzky and his colleagues are examining how immigrants assimilated into American society by tracking migrants from 16 European countries through three decades of U.S. Census records. Immigrants, they've found, kept pace with the economic growth of their native-born American peers.

Hans Gabrielsen and his family eventually settled in Utah, where he worked as a successful carpenter for many years. His descendents number in the hundreds, with many carrying his distinctively Norwegian last name.

Paul Gabrielsen is an intern at the Stanford News Service.

-30-

|