|

April 15, 2013

Turbulent seas signal sea urchin larvae to settle down, Stanford scientist discovers

Sea urchins mature prematurely in swirling coastal waters to avoid missing their chance to find a home on rocky shores. By Thomas Sumner

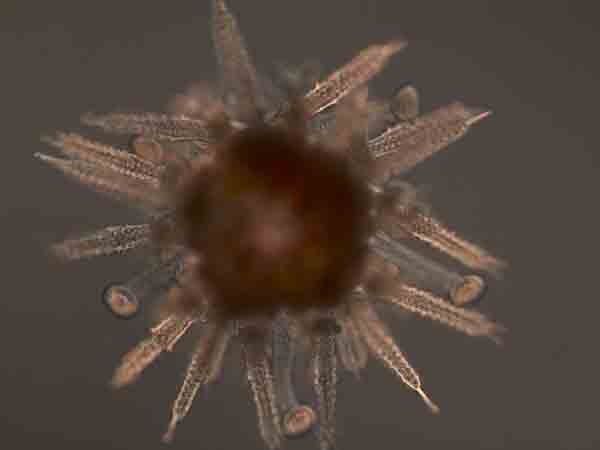

Sea urchins in turbulent waters will prematurely go through puberty and attach to coastal rocks to avoid being washed back out to sea. But a juvenile that matures early may not be sufficiently robust to hang on tightly with its suction cups. (Photo: Jason Hodin)

The swirling waters of a rocky shore motivate sea urchin larvae to grow up and settle down.

Scientists, including Stanford marine biologist Jason Hodin, discovered that young sea urchins will prematurely go through puberty and attach to coastal rocks to avoid being washed back out to sea permanently. The researchers published their findings April 9 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"Even if they're a bit immature and it will decrease their chance of surviving as a juvenile, it's worth it because the sea urchins might get swept back out to sea and never make it back to the seashore," said Hodin, a research scientist at Stanford's Hopkins Marine Station.

Urchin life

Sea urchins begin their two-part life cycle as tiny larvae the diameter of a human hair. Looking drastically different from their prickly parents, the larvae drift along the upper ocean for a month feasting on phytoplankton until they grow to about 10 times their original size.

When a grown sea urchin larva washes into coastal rocks, it will turn its body inside out and transform into an adult, latching itself onto the shore.

"It may be matured enough to transform and settle down, but it still needs the correct habitat," Hodin said. "If it makes a bad decision and chooses the wrong place to settle, like on the seafloor, it won't be able to move again and won't survive."

Sea urchins go for a spin

Marine biologists had known sea urchin larvae can "smell" nearby coastal rocks, but they didn't know what role the tumbling coastal waters played in signaling physical transformations in the larvae. Hodin and co-author Brian Gaylord, a professor of evolution and ecology at the University of California-Davis, placed sea urchin larvae in a special contraption called a Taylor-Couette cell to mimic the coastal environment.

A Taylor-Couette cell is made up of one cylinder inside of another with water filling the gap between them. When the inner cylinder is held still and the outer cylinder is quickly rotated, the water is sloshed around chaotically and turbulence appears. The device was originally invented to study fluid dynamics.

"I've always been curious about what it's like to be a larva," Hodin said. "It's really fun to be able to see what a larva looks like after it's been exposed to this intense turbulence for a while. They look dizzy under the microscope."

When the researchers added potassium to the mixture – one of the chemicals young larvae "smell" coming off of seaside rocks – the larvae began to transform and settle down at a stage of development much earlier than previously thought possible.

These early life changes happened only when both the chemical cue and the turbulent environment were present, meaning both factors were required to begin the settling process. A wild larva would first feel thrashed about in the near shore waters and then begin searching for the chemical cue to begin the settlement process, Hodin said.

This early transformation wasn't what the researchers were expecting or even searching for. Originally the experiment was designed to test whether an acidic environment would damage young sea urchins as they were splashed into the coast.

"We initiated the experiment with the idea that the larval skeletal arms might get broken when exposed to turbulence," Gaylord said. "What we saw instead was an enhancement in the settlement. It ended up being the reverse of what we had expected."

Growing up fast

Transforming into the adult phase of their adult cycle so early has downsides for the sea urchins, Gaylord says.

"At an early developmental stage the little structures with suction cups on the end that secure them to the rock might not be as robust as they need to be and they could be pulled away by the rapid water," he said. "They might also not be able to acquire food as quickly or protect themselves as well against predators."

But since sea urchin larvae spend so much of their time out at sea, the downsides of a shortened childhood might be worth the risk if it helps them find a place to settle down.

"They might be thinking to themselves, 'This is the last chance we have in our life to find a good place to settle. If we finally made it back from the open ocean to the near shore, this might be the time to do it,'" he said.

Detecting turbulence

The mechanism that the larvae use to detect turbulence is not yet clear, Hodin said. One theory is that special receptors along the larvae's body stretch and flex as water rushes by.

Similar mechanisms and two-step settlement processes might be common for other shoreline species, which the team plans to study in future experiments.

Thomas Sumner is an intern at the Stanford News Service.

-30-

|