|

January 23, 2012

Elliott Levinthal, Stanford professor emeritus of mechanical engineering, dead at 89

In a career that ranged from radar to medicine to outer space, Elliott Levinthal played an instrumental role in the schools of Engineering and Medicine, and in the rise of Silicon Valley.

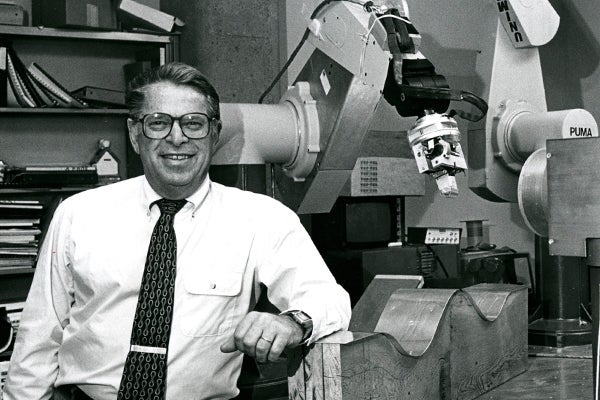

In addition to his work in engineering and medicine, Elliott Levinthal was a generous supporter of the humanities. Among his efforts was establishing the Levinthal Tutorials program in creative writing at Stanford. (Photo: Chuck Painter / Stanford News Service archives) Elliott Levinthal, Stanford professor emeritus of mechanical engineering, died of natural causes on Jan. 14 at his home in Palo Alto. He was 89.

Levinthal was born in Brooklyn on April 13, 1922. He graduated from Columbia in 1942, received a master's degree from MIT in 1943 and a PhD from Stanford in 1949. During World War II, Levinthal worked with Sperry Gyroscope, where he earned a patent for the discovery that detuning the intermediate cavities of multi-cavity klystron amplifiers increased their efficiency, an important development in klystron design.

While at Sperry, he developed relationships with faculty members in Stanford's Physics Department, in particular electronics pioneers Russell and Sigurd Varian and Ed Ginzton. These friendships prompted him to continue his studies at Stanford. As doctoral candidate he worked under the direction of Nobel laureate Felix Bloch. Levinthal's dissertation, on the magnetic resonance of the hydrogen atom, was part of Bloch's Nobel-winning discoveries in magnetic resonance.

After completing his doctorate, Levinthal joined Varian Associates as one of the founding employees, rising to serve as research director and, ultimately, as a director of the company. Varian purchased the rights to the Bloch patents and Levinthal was responsible for developing them into commercial instruments, laying the groundwork for use of nuclear resonance as a tool in chemistry and biochemistry.

In 1953, Levinthal founded his own company, Levinthal Electronics Products, which developed some of the first defibrillators, pacemakers and cardiac monitors.

In 1961, he joined the Genetics Department of the Stanford School of Medicine, where he worked with Joshua Lederberg on exobiology, examining the question of extra-terrestrial life and designing experimental missions to Mars. This led to Levinthal's service on a number of NASA and National Academy of Sciences committees. He became a member of the photo interpretation team of the Mariner 9 Mars Orbiter missions and deputy team leader of the Viking 1976 Lander Camera Team.

At the medical school, he became a research professor and director of the Instrumentation Research Laboratory. The laboratory was active in the design and operation of mass spectrometers and their computer control and analysis. As associate dean for research affairs at the medical school, he developed computer systems for the Medical Center, which led to the creation of SUMEX-AIM, the Stanford University Medical Experimental Computer for Artificial Intelligence in Medicine.

During a three-year leave from Stanford, he served as director of the Defense Sciences Office at DARPA, the Advanced Research Projects Agency in the Defense Department. His responsibilities there included materials science, geophysical sciences, electronic science and system sciences. He also introduced programs in the biological sciences and robotics.

Returning to Stanford, Levinthal became a research professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and director of the Stanford Institute for Manufacturing and Automation (SIMA). He later became associate dean of research at the School of Engineering.

In addition to his academic roles, Levinthal was active in the development of a number of Silicon Valley companies. He was involved in Arthur Rock's investment partnership, the first venture capital fund in Silicon Valley, and served as director, science consultant and science advisor for several companies dealing with medical or biological questions. He was a founder of Neuroscience, later renamed Eunoe, which pursued research on devices to filter cerebrospinal fluid to treat Alzheimer's disease.

Levinthal was an active and generous philanthropist. He provided financial support to less advantaged students to attend Stanford and was a generous supporter of the humanities. His philanthropy included the establishment of the Levinthal Tutorials program in creative writing at Stanford University. Levinthal was also active in local and national politics. He had a great love of travel, leading him to all seven continents in his adventures.

His greatest passion, however, was his family. Levinthal is survived by his loving wife of 67 years, Rhoda, of Palo Alto; four children, David (Kate) Levinthal of New York City, Judith (Randall) Levinthal of Santa Monica, Calif.; Michael Levinthal of Park City, Utah; and Daniel Levinthal of Philadelphia; as well as seven grandchildren: Aaron, Leah, Asher, Adam, Zach, Katie and Sam.

A small family service has been held. Gifts in Levinthal's memory can be made to the Stanford Creative Writing Program.

-30-

|

|