|

September 21, 2012

Stanford scholars search for documents from the Chinese workers who built the U.S. Transcontinental Railroad

With help from the public, the Stanford-led project will give a voice to the Chinese migrants whose labor on the Transcontinental Railroad helped to shape the physical and social landscape of the American West. By Corrie Goldman

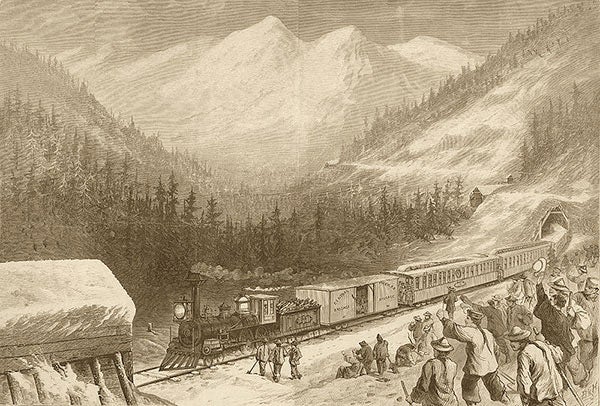

Depiction of Chinese workers greeting a train as it travels through the Sierra Nevada. That Chinese migrants contributed to building the railroad is well known throughout the world, but there is little actual knowledge about their work, identities and experiences. (Photo: Library of Congress via Wikipedia)

Between 1865 and 1869, thousands of Chinese migrants toiled at a grueling pace and in perilous working conditions to help construct America's First Transcontinental Railroad.

At any given moment during construction, 10,000 to 15,000 Chinese workers were on the job. And yet remarkably, not a single document created by one of these workers – not even a letter – has ever been found.

Two Stanford scholars are leading a multi-year, transnational research endeavor that aims to finally give a voice to the Chinese laborers whose blasting techniques and sheer fortitude built the railway across the inhospitable mountains of the Sierra Nevada.

In an effort to produce a body of scholarship that will be the most authoritative study on the Chinese railroad worker experience in America, the project organizers are appealing to the public in the hopes of locating long lost documents.

"We would like to hear about any family papers that may include material by or about Chinese railroad workers," said project co-organizer and American studies scholar Shelley Fisher Fishkin.

Scholars and institutions interested in taking part in the search for relevant materials are also encouraged to partner on the project or to suggest archives that may have been previously overlooked.

By consolidating existing scholarship and uncovering new archival materials in English and Chinese, the "Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project" will give researchers and the public valuable insight into not only the experience of the workers but a neglected facet of American history.

"It is impossible to talk about the economic, political and cultural rise of the Western U.S. without a discussion of the Chinese," said historian and project co-organizer Gordon Chang.

That the Chinese contributed to building the railroad is well known throughout the world, but there is little actual knowledge about their work, identities and experiences.

Fishkin said that although legends abound and some scholarly work has been produced, "These workers have never received the attention they deserve."

In addition to the recovery of primary materials, Fishkin, a professor of English and director of Stanford's American Studies Program, emphasized that the researchers are interested in understanding how the workers were portrayed in the cultural memory of the United States through literature, film and other art forms.

Fishkin said the project taps into her research interests of "race and racism, neglected voices, and the transnational nature of American history and culture."

Chang, the director of Stanford's Center for East Asian Studies, said that the fact that we have documented so little of the Chinese railroad workers' experience is "a telling commentary about race and our nation."

Although the labor of these workers helped build the fortune with which Leland Stanford founded the university, Fishkin said she was struck by how "their contribution is invisible on campus."

An international search

A fourth-generation Chinese American and Californian, Chang has long been curious about the dearth of primary source materials from the period. Historians, Chang said, "know that the workers left records, sent letters and remittances to China and interacted with others in the West." Chang speculated that their records were discarded because their work on the railroad was "considered marginal to the story."

What few immigration records may have existed were likely destroyed during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fires, Fishkin added.

China seems like the next obvious source of records, but none has been found there either. Chang said the string of wars, revolutions and political campaigns in China over the past 150 years have destroyed much of China's past, although he remains "hopeful that materials will surface if we look hard enough."

The international team of academics working on the project will assemble a registry of descendants of Chinese railroad workers in the United States and China. Fishkin said they would like "anyone whose family history includes a railroad worker to tell us about their relative."

The researchers also seek to identify museums and archives in China and elsewhere "that are interested in the collaborative use of digital technologies to share and preserve these invaluable materials," Fishkin said.

Project researchers are already beginning to work with archives and libraries in China and will be approaching government offices. Because Chinese work on the U.S. rail line was part and parcel of a "much larger story of Chinese migrant labor and exploitation," Chang believes that many in China will be "deeply interested in uncovering the story."

Multidisciplinary collaboration

Given that scholars have already spent decades combing the globe for pertinent materials, there is a possibility that none will surface this time around. But even if that's the case, all is not lost.

"The possibilities that the digitization of archives in both Chinese and English opens up will allow us to explore a range of issues that were previously very difficult to explore," said Fishkin.

Chang and Fishkin are collaborating with Dongfang Shao, the former director of Stanford's East Asia Library and now the chief of the Asian Division of the Library of Congress, and Stanford alumna Evelyn Hu-DeHart, a history professor at Brown University.

Project investigators include prominent scholars based in the United States, Canada and Asia with backgrounds in diplomatic history, business history, social history and public history; from cultural studies, literary studies, translation studies, ethnic studies and American studies; from archaeology, art and anthropology.

In early September, participating scholars from around the world joined Fishkin and Chang at Stanford to brainstorm about the best ways to capture and tell this important transnational story.

Undergraduate interns at Stanford have begun to compile primary and secondary sources, such as pamphlets, journals, photos and periodicals, which will help scholars see what is currently available in published sources.

The project will culminate with an online multi-lingual digital archive of historical materials, conferences in 2015 at Stanford and in China, and the publication of a book featuring new scholarship. The project and its resources will be housed in Stanford's East Asia Library.

The project was aided by grants from the office of Stanford President John L. Hennessy and the UPS Fund at Stanford.

To submit materials or for information about collaborating on the project, contact Hilton Obenzinger, planning coordinator of the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project, at hobnzngr@stanford.edu.

For more news about the humanities at Stanford, visit the Human Experience.

-30-

|