|

January 13, 2012

Stanford's Clayborne Carson on the meaning of the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial

By Corrie Goldman

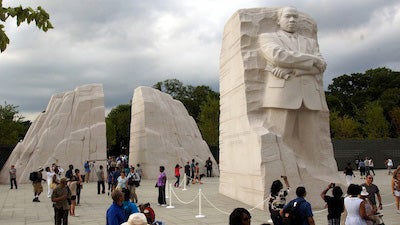

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. on its dedication day, Oct. 16, 2011. (Photo courtesy of Clayborne Carson) In October, over 50,000 people gathered at the National Mall in Washington, D.C., to witness the dedication of the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial.

Professor Clayborne Carson, a Stanford historian whose scholarship centers on King, was among those in attendance who remembered seeing King give his "I Have a Dream" speech on the Mall in 1963. Carson, director of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute at Stanford, played an integral role in the design of the site.

Carson, who was personally chosen by the late Mrs. Coretta Scott King to edit and publish King's papers, was invited by San Francisco's ROMA Design Group to collaborate on a proposal for a memorial.

Drawing from his personal and academic knowledge of King, Carson advised architects, urban planners and landscape designers on concepts ranging from the orientation of the site to the inclusion of large-scale natural and built elements. Carson found inspiration in King's metaphorical language.

At the request of the King Memorial Project Foundation, Carson supplied the quotes seen on the 450-foot-long "Inscription Wall."

What was your initial reaction to being invited to consult on the design of the memorial?

Bonnie Fisher, the landscape principal of the ROMA Design Group in San Francisco, called me to ask whether I would collaborate with her firm in an international design competition sponsored by the King National Memorial Project Foundation. Her query was not entirely unexpected, given my long association with King's legacy. As the historian selected by Mrs. Coretta Scott King to edit her late husband's papers, I had already been contacted by the Memorial Foundation to supply information about King for a poster advertising the design competition. I was wary, however, of any new distraction from my ongoing effort to publish a definitive multi-volume edition of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. When Bonnie arrived at the dinner with her husband, ROMA's president Boris Dramov, my intention was merely to offer advice and wish them well in the competition. Nonetheless, I was soon impressed by Bonnie's pert enthusiasm as she described ROMA's "interdisciplinary" approach, bringing together architects, landscape architects and urban planners to redesign urban environments.

How did your background influence your collaboration and communication with the architects?

My views of King had changed since the 1960s, when I saw King's speech at the march but was more intrigued by the grassroots organizing "bottom-up approach" of his youthful critics in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Even after becoming director of the King Papers Project, I still criticized the popular tendency to ignore King's provocative anti-war and anti-poverty speeches while giving excessive attention to his extemporaneous "I have a dream" refrain at the march. I saw King as more than simply a charismatic orator but nonetheless had to concede the remarkable impact of his most famous sound bite. It seemed obvious that a King Memorial built near the Lincoln Memorial should celebrate the Dream speech and the man who eloquently expressed the larger historical significance of the African American freedom struggle.

What symbolic elements did you consider essential?

Although I had no expertise in landscape design, I recommended that the design visualize the vivid metaphorical language of King's 1963 oration. Calling up familiar passages from memory, I suggested some possibilities for visual themes. King's insistence that black Americans would "not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream," for example, might readily be expressed through fountains and running water. The evocative images King had used to illustrate his "dream" of a future America offered other possibilities. Then we focused our attention on a less often quoted passage: "With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope." King's extended metaphor suggested dramatic large-scale elements for a memorial that would celebrate an inspirational advocate of racial justice as well as a famous orator.

Visitors to the site pass through two towering granite stones of a "Mountain of Despair." They then encounter the removed section, the "Stone of Hope," in which King's likeness is carved. How is the placement of these pieces meant to impact the visitor experience?

We imagined visitors to the memorial entering through an opening cut through the granite core of a Mountain of Despair. The removed slice – the Stone of Hope – would be thrust forward and turned slightly so that visitors entering through the Mountain would encounter an inscription of King's words on the slab's smooth surface.

You have written that the "only point of contention was whether the design would include a statue of King."

I resisted the idea of a heroic Great Man representation of a man who often described himself as simply a symbol of the movement. I had also been unimpressed with the bust of King I saw unveiled in 1986 at the Capitol Rotunda in Washington and recognized that it was difficult to create a convincing sculpted image of a man depicted in numerous iconic photographs. For many of his admirers, King's inspiring words made him seem taller and more imposing than his actual 5-foot, 7-inch stature. Bonnie and Boris persuaded me, however, that many visitors – and perhaps the jurors for the competition – would miss seeing a statue of King. We settled on the idea of sculpting an image of King into the rough edge of the Stone of Hope facing toward the Tidal Basin. Visitors standing at the edge of the Basin would be able to turn back to see King's visage as an integral feature of the Stone. As Boris explained at the time, the image would be "unfinished, allowing people through their own memories to complete the picture."

There are no quotations on the monument from King's "I Have a Dream" speech. Why?

The original design by ROMA and me included a quote on the side of the Stone of Hope from the Dream speech. I proposed that we feature a passage near the beginning of his prepared text. King reminded his audience that "the architects of our republic" had signed "a promissory note" – "a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." King's call for the nation to "live out the true meaning of its creed" would, I expected, serve as a continual reminder to Americans that their nation had still not realized some aspects of his dream. ROMA's Stone of Hope drawings were based on a famous Bob Fitch photograph showing King in his office in a pensive pose – we imagined him taking a break from drafting his reference to the "promissory note" and looking across time and the Tidal Basin toward Jefferson, one of the nation's founding architects and principal author of the Declaration of Independence. The two men would serve as historical frames for a perpetual dialogue about the meaning of American democracy. Although I was consulted about the quotes for the memorial, the head architect from the Memorial Foundation rejected, over my strong objections, my idea of placing the "promissory note" on the Stone of Hope, arguing that the quote was too long.

The north face of the statue features this quote: "I was a drum major for justice." Excerpted from a lengthy sermon, critics say the quote sends the wrong message out of context and should be removed or corrected. What's your interpretation of the quote?

The quote should not have been abridged, because it sends a misleading message. It should be corrected to include the entire passage.

How can a monument such as this inspire future Americans to engage in social activism and to further King's ideals?

Like the other memorials on the National Mall, the King Memorial will serve as a place where visitors can reflect on King's significance as a symbol for America's struggle to realize its democratic ideals.

-30-

|