|

June 29, 2011

Stanford artist Richard Randell dies at 81

Randell was known for his large-scale contemporary sculptures in bronze, wood, plastic and neon as well as his videos on African languages. He was also known as "a very cool professor." By Cynthia Haven

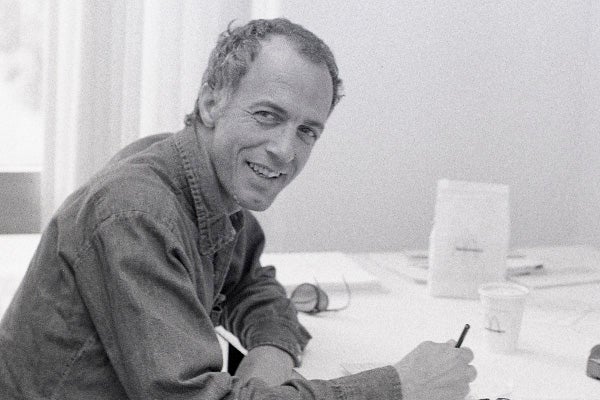

Said one friend about Richard Randell: "He was always young, until the day he died." (Photo by Jose Mercado / Stanford News Service) Richard Kenneth Randell, a former Stanford professor and nationally known artist and sculptor, died at his Windsor, Calif., home in Sonoma County on May 25 of lung cancer. He was 81.

Randell was known for his large-scale contemporary sculptures. Later, in the 1990s, he also worked on African-language video projects for students studying Kiswahili, Hausa, Shona and Bambara languages.

Wanda Corn, professor emerita in art history, called him "a gifted sculptor, adventurer and storyteller."

"He had a great sense of irony and the absurd," she said. "Students loved him for his talk and wisdom as well as his teaching of metal and woodworking."

Randell was born in Minneapolis on Dec. 30, 1929. He showed an early interest in athletics, entering boxing competitions and eventually dancing ballet professionally. But his interest in art became a more enduring professional passion. He studied filmmaking and sculpture at the University of Minnesota and graduated with a bachelor's degree in studio art in 1953.

As a young artist he went to New York and was represented by the Marks Gallery, at that time one of the city's biggest sculpture galleries. He would go on to exhibit his work at the Museum of Art of the Carnegie Institute, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and other galleries and museums throughout the country.

He taught sculpture at the University of Minnesota-Minneapolis from 1961 to 1966, where he produced a film about the lost wax method of casting for bronze sculpture, which was no longer widely practiced. The film encouraged and instructed artists who wanted to reintroduce the art. He also filmed documentaries and nature films.

During this period, he built a foundry in Mendota, Minn., and acted as a technical consultant to the Racine Art Foundry of Detroit.

He joined the Stanford art faculty in 1970, after serving as an acting assistant professor of art at the university in 1968-69.

Though known during those years for his metalwork, his interests ranged widely. Mona Duggan, associate director of the Cantor Center for Visual Arts and a friend, recalled him becoming fascinated with the possibilities of working in such materials as plastic and neon.

"Whenever Richard took on a new interest, he went into it in depth, until he mastered it," said Duggan.

Largely because of the breadth of his knowledge and up-to-the-moment interests, she said, "he was also a very popular teacher. Particularly in the late 1970s and 1980s, he was known by his students as a very cool professor."

"He was always young, until the day he died."

In 1992, Randell founded a nonprofit corporation called World of Languages to support his work with linguists from Stanford, Yale and the University of California-Los Angeles who were creating a video archive for the disappearing songs, poetry and dances of Kenya and Tanzania. He received a grant from the Department of Education and a Fulbright Fellowship for his work.

He also filmed and directed a series of video stories in Nigeria to be used for Hausa language learning at UCLA.

A grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities funded a multimedia language and culture "textbook" for Hausa, the native language of 30 million people. Randell and his colleagues videotaped life in the markets, homes and workplaces of Kano, Nigeria, where this widely spoken language was in everyday use.

In a 1999 Stanford exhibition, the video ran simultaneously with recordings of goge and kuntigi (musical instruments) from Nigeria, and Kenya's Swahili singers. Photographs of Catholic youth choirs, sword dancers and flute players were hung on a nearby wall.

The exhibition also included Randell's massive bas-relief sculpture that climbed one wall and arched over the ceiling, featuring a distorted hand, gun and bullets.

After his retirement in the late 1990s, he enjoyed creating stop-motion animations, mostly from the African and Italian folk stories that he collected during his travels. His animations won awards in Berkeley film festivals. He was granted two artist residencies at the Emily Harvey Foundation in Venice where he sketched and researched people, costumes and stories from the city's history.

He learned to ride horseback and competed in cross-country and dressage events. He built and sailed three boats.

Randell is survived by his wife, Susan Harby of Windsor, and four children: Douglas Randell of Woodland, Calif., Tracy Randell Gibson of Tucson, Ariz., Megan Cosgrove of Egan, Minn., and Christopher Randell of Mendota, Minn.

A memorial service will be held this fall. Details for the service are being planned, and Harby asks that friends and colleagues contact her at susanharby@aol.com.

-30-

|