|

September 20, 2011

Stanford takes Estonia's 'Museum of Occupations' under its wing

"While the Cold War may be over, history goes on, and it is the role of universities, and very much that of their libraries, to serve as institutions of cultural memory," said Stanford Librarian Michael Keller. By Cynthia Haven

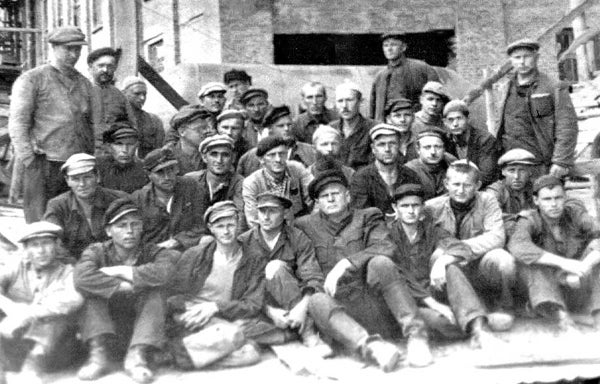

Estonian political prisoners in the Ivdel camp in Ural Mountains on Aug. 14, 1954. (Photo: Courtesy of Museum of Occupations) Olga Ritso Kistler arrived in Estonia from the Ukraine as a malnourished, flea-ridden toddler in 1923, in the wake of the upheavals of the Bolshevik Revolution. Her mother was dead, her father imprisoned in Siberia. By 1940, her life was in turmoil again as she watched as the Soviets, then the Nazis, and the Soviets again, swallowed the small nation that had enjoyed a brief, interwar independence.

Now the Estonian American medical doctor continues her efforts so that the rest of the world remembers the plight of the Baltic states, crushed between the Soviet and Nazi totalitarian powers – and Stanford will help her do it.

At a Sept. 13 ceremony in Tallinn, Estonia's capital, attended by Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves, representatives of the American Embassy and Estonian officials and academics, the museum announced a collaboration with Stanford to advance its mission and widen its message to a worldwide audience.

Ritso Kistler founded Tallinn's Museum of Occupations in 2003, at the request of the Estonian government.

"[I]ts purpose is to show future generations how terrible the decades of Soviet rule were, a time when no one was allowed to believe in a free and independent Estonia," wrote Cambridge historian Peter Martland in a privately published volume on the family's history, Footprints in the Sands of Time.

The striking, modern building is located in the heart of Tallinn. The museum documents the three occupations of Estonia: the first Soviet occupation from 1940 to 1941, the German occupation from 1941 to 1944 and the second Soviet occupation from 1944 to 1991. Through its exhibition of thousands of items from the three occupations and a modest research program, the museum has informed tens of thousands of visitors each year of the deprivations, arrests and deportations and daily control of even minute details in the everyday lives of Estonians and others in the Baltic region.

The Stanford University Libraries will expand its collecting program in Estonia and the Baltic region as well as collaborate on exhibitions with Estonia's Museum of Occupations, thanks to a $4 million endowment from Walter P. and Olga Ritso Kistler. The foci of the collecting program will be wider than occupation, however, involving in addition the Estonian resistance, the many aspects of the so-called Singing Revolution that led to freedom and the modern renaissance that has occurred in Estonia since the early 1990s as the society, government and economy have recovered from the occupation by Soviet Russia.

"While the Cold War may be over, history goes on, and it is the role of universities, and very much that of their libraries, to serve as institutions of cultural memory," said Stanford University Librarian Michael Keller. At least two Stanford history professors, Norman Naimark and Amir Weiner, are already engaged in research on the Estonian experience.

"The struggle of small nations for autonomy in the shadow of empires is something we should all remember and recognize as an ongoing concern. The 9/11s and December 7ths do not need our help being remembered, but the fate of the Baltics – at least from this distance – certainly does," according to Keller.

Stanford will appoint an Estonian curator to be based at Stanford; the new curator will collect and prepare exhibitions for U.S. and Estonian audiences. According to the agreement, the museum in Tallinn also will promote scholarship and appreciation of the human spirit in the direst circumstances.

Keller and his successors will represent Stanford on the board of the Kistler-Ritso Estonian Foundation, founded by Olga Ritso Kistler, which currently operates the museum. He also will appoint an advisory committee for the museum, including at least one Hoover Institution fellow and several Stanford faculty, among other experts.

The average Westerner is likely to think there is plenty of material documenting the occupation – but not so. State institutions charged with such research are strapped for cash and other resources. Much research and synthesis of findings remains to be done. Moreover, time is running out, as a generation of memories dies.

The museum includes a row of prison cell doors, suitcases from deportees, a Soviet era telephone booth, books, posters, badges, pins and even bugging equipment.

The website itself is a virtual museum of its own, including photos and films.

Olga Ritso Kistler was born in Kiev in 1920. Her mother, weakened by hardship, died when Olga was 2; her maternal grandparents were among the millions who starved to death in the 1921 manmade famine. Her father, an Estonian patriot and physician, was a fugitive from the Bolsheviks in the Ukraine but was later arrested in Moscow in 1922.

Raised as a foster child in Estonia, the young girl was reunited with her father only in 1931. Dictating his memoirs to her, he recalled the Soviet and Nazi deportations and the Holocaust that, altogether, resulted in the loss of about a quarter of the Estonian population.

After the Soviet invasion of 1939-40, she recalled: "It was such an awful, horrible time … the Soviets started killing everyone who was anyone … there wasn't a single family that didn't have a relative or friend taken away." As a young medical student, she stayed with different friends each night to avoid deportation to Russia.

To flee the Soviets, she escaped from Estonia in 1944. In postwar Germany, she was a medical officer in a displaced persons camp. She immigrated to the United States in 1949.

Her story had a happy ending. At age 40, the eye surgeon married entrepreneur and inventor Walter Kistler, who developed instrumentation for NASA and the industrial world. The nonagenarian couple now lives near Seattle.

Their daughter, Sylvia Thompson, president of the Kistler-Ritso Estonian Foundation, and son-in-law, Andrew Thompson, are both Stanford alumni, each with two Stanford degrees.

With Stanford's help, Olga Ritso Kistler is realizing the dream that began over a decade ago when she created a foundation to gather, collect and study the consequences of the Estonian occupations. As the museum's website states: "Our dead will remain unburied until the memories of those that perished are immortalized."

-30-

|