|

May 17, 2011

Philip Hanawalt wins Princess Takamatsu award, looks back on 50 years at Stanford and ahead to turning 80

In his 50 years on campus, biology professor Philip Hanawalt has made major discoveries in the field of DNA repair and has received numerous awards. He has recruited promising young researchers from around the world to his lab group and is still active in his field, even though he's soon to turn 80. By Louis Bergeron

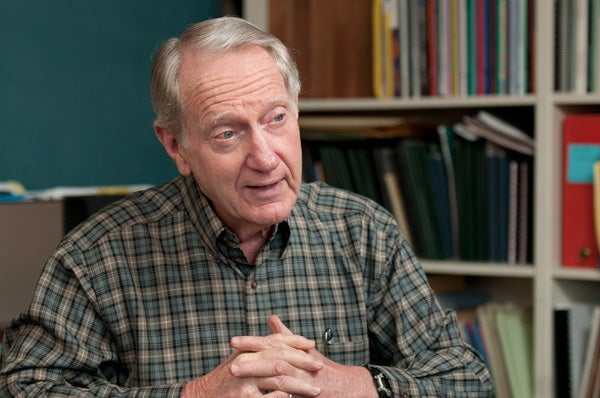

In September, biology Professor Philip Hanawalt will mark, as he put it, 'My first 50 years on the faculty at Stanford.' (Photo by Linda A. Cicero / Stanford News Service) In a career that has garnered many accolades – for research, for teaching and for mentoring – one recent award holds particular significance for Stanford biology Professor Philip Hanawalt: the Princess Takamatsu Memorial Lectureship.

Hanawalt delivered the lecture, "Transcription, DNA Repair and Cancer," last month at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research in Orlando, Florida.

Hanawalt knew the late Japanese princess, having attended two of the invitation-only cancer research meetings she held annually. Princess Takamatsu became interested in cancer research after her mother died from the disease in 1933, at age 43.

At his first conference, Hanawalt expected the princess to make only a brief appearance. Instead, she sat down at a table at the front of the room, put her purse on the table, took out her glasses and proceeded to deliver a 15-minute talk. "That impressed me," Hanawalt said. "She followed the field of cancer research very closely and seemed quite knowledgeable about the biochemical aspects of the disease."

The lectureship award has been given annually by the American Association for Cancer Research, beginning in 2007, and includes an honorarium of $10,000.

Hanawalt was chosen in recognition of "his pioneering work in the field of DNA repair and his contributions to our knowledge of how cellular processing of damaged DNA relates to human cancer."

In other milestones, this September he will complete, as he put it, "My first 50 years on the faculty at Stanford." In August, he will complete his first 80 years of life.

Arriving at The Farm

"Stanford has been a wonderful place to grow up and have my career," Hanawalt said.

He had just turned 30 when he arrived at Stanford in 1961 and was already on the research trajectory that would lead him to his first major discovery, in 1963, that DNA was not the extraordinarily stable chemical that most scientists then thought.

Hanawalt and his former PhD adviser, Richard Setlow, then at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, were working with the bacteria E. coli and seeking to understand how the cells were able to replicate their DNA and remain viable under the onslaught of ultraviolet radiation damage from the sun. They discovered that enzymes in the cell were constantly repairing the damaged DNA.

"Dick Setlow discovered that damage gets cut out of DNA and I discovered that repair patches are put in," Hanawalt recalled. "It is really the combination of those two that constitutes the first discovery of DNA repair." The process is called repair replication.

Most researchers had reasoned that DNA – which contains the hereditary genetic code for the development and maintenance of each living organism – had to be extremely stable, or it couldn't possibly be successfully replicated in each new cell of an organism.

Instead, Hanawalt said, "DNA is constantly monitored [by enzymes] and damage is removed and repaired. If that did not happen, we would not be here."

Of mice and men

On most days, "here" for Hanawalt is his office of 44 years in the Herrin Biology Laboratories, which formerly housed all the mice used by researchers in the building.

In 1967, his research program was outgrowing his limited lab space in Herrin and he cast his eye on the mouse room. "I felt that the mice didn't need the view of the Palo Alto sunset that was visible from the windows at that time," he said.

So he contacted Donald Kennedy, then chair of the Biology Department. "I wrote to Kennedy and said, 'It is time to convert the mouse room to a man room'," Hanawalt recalled. "And he replied, 'You may proceed in all due haste to convert the mouse room to a Men's Room.' " The mice were relocated to the building's basement.

Settled into the new quarters, Hanawalt and his lab group went on to more discoveries, including another way that enzymes initiate DNA repair that removes damage that interferes with reading the genetic instructions from the blueprint DNA. That information is needed to guide production of the proper proteins in the cell.

The process, called transcription-coupled repair, was discovered in 1984.

Hanawalt's work on DNA, along with that of some other researchers, was weighty enough to prompt Science to name the DNA repair enzyme the Molecule of the Year in 1994.

In biology, everything evolves

Hanawalt was chair of the biology department from 1982 to 1989. Since then the faculty has more than doubled, and science itself has changed in the way it is done.

More and more, Hanawalt said, developing major advances requires a large group of researchers and a big facility, because of the complexity of the research projects. "But novel insights still usually come from individuals, rather than committees," he said. "Most of my enjoyment in science is working with a small group of people and talking about ideas."

Hanawalt has reduced the size of his lab group in recent years. He no longer accepts graduate students, as he's not sure that he'll stay active long enough to see them through the years it takes to earn a PhD. But he still has several research associates and usually has three or four undergraduates working in the lab.

Hanawalt likes working with undergraduates. "They come in fresh and eager and without the preconceived models and ideas that I have, having been in the field for a long time," he said. "So they come up with new ideas." Of the two courses he teaches, his favorite is the freshman seminar, "Maintenance of the Genome."

Hanawalt doesn't get into the lab much these days, in part because he is on the editorial board for Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reviewing research papers submitted for publication.

Science that knows no borders

Throughout his career, Hanawalt has recruited students from around the world and has tallied 35 countries of origin among his lab group. Members of his current group hail from Nepal, Mexico, Russia and China, plus one more from Argentina: Graciela Spivak, his wife of 32 years. A senior research scientist, she has been active in the lab all 32 years and was involved in the early studies on transcription-coupled repair.

Hanawalt said that one person's work hardly ever prompts an award, but rather the efforts of a group such as his students and colleagues. "Any award that I get, such as the Princess Takamatsu lectureship, is due to these people," he said. "I'm very proud of them and so I humbly accepted the award on behalf of those folks."

Hanawalt's former students are scattered across the globe and he warns them he may visit them all if he ever retires. He has his own pair of airline seats gracing his outer office, should he decide to jet off – a gift from Professor Robert Simoni, who succeeded him as chair, in appreciation of Hanawalt's official travels. "They are perfectly good economy class seats and there is still some food on the tray tables," Hanawalt said.

But even with all those inducements, he seems in no hurry to fly off into the sunset. "This is the best of possible places for me to have a career," Hanawalt said. "I have had opportunities to go elsewhere and I have not given them a second thought."

Hanawalt holds the Dr. Morris Herzstein Professorship in Biology.

-30-

|