|

August 11, 2011

Scientists must leave the ivory tower and become advocates, or civilization is endangered, says Stanford biologist Paul Ehrlich

Scientists, especially ecologists, have to be more active in explaining the meaning of their research results to the public if human behavior is going to change in time to prevent a planetary catastrophe, says biologist Paul Ehrlich. By Louis Bergeron

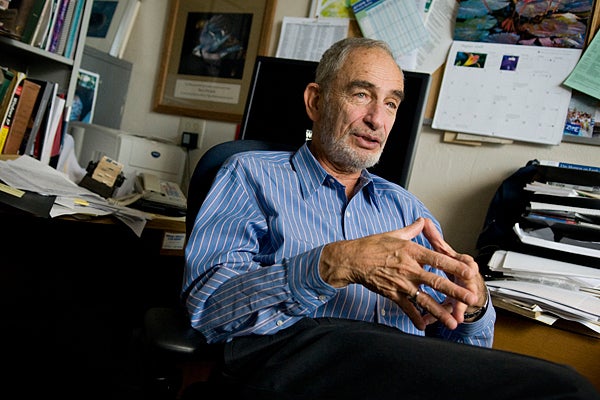

"The idea that ecologists shouldn't be advocates, that they shouldn't be telling the public that what ecologists study is basically disappearing, is just nuts," said Paul Ehrlich, Stanford professor of population studies. (Photo: Linda A. Cicero / Stanford News Service) Paul Ehrlich summed it up this way: "You often hear people say scientists should not be advocates. I think that is bull."

Ehrlich, the Bing Professor of Population Studies at Stanford, will be elaborating on that theme and several others when he speaks Thursday at the annual meeting of the Ecological Society of America in Austin, Texas.

In an interview a few days before the meeting began, he talked about the urgent need for scientists to take their research results and use them to inform the public about the threat of global environmental collapse. No longer can researchers consider publishing their results in a journal, no matter how prestigious, the end of their obligations.

"With society moving toward a collapse, the idea that scientists, especially ecologists, should just do their work, present their data and not do any interpretation leads to the kind of imbecility we have in Washington today, where you have an entire Congress that is utterly clueless about how the natural world works," Ehrlich said.

He said that scientists, before they embark on a research project, should ask themselves, "How, if my research yields all the results I'd hoped for, will it make any difference to the world?"

The once-dominant paradigm of "curiosity-driven" research being the "purest" way to do research is outmoded. "How you judge a good scientist, in part, is by what they choose to be curious about," he said.

It is also critical, he said, that the work ecologists do be of the highest quality and of general scientific interest. Ehrlich said he would love to see prominent peer-reviewed journals such as Science, Nature and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences flooded with top-notch ecology research with clear connections to the human condition.

Calling ecology the most important science today, in light of the environmental crises that are looming ever larger on a horizon that is coming ever closer, Ehrlich said that ecologists have a singular responsibility to get their work into the public eye.

"The idea that ecologists in particular shouldn't be advocates, that they shouldn't be telling the public that what ecologists study is basically disappearing, is just nuts," he said.

For the first time in human history, a complex global society is at risk of environmental collapse. Human behavior is not changing fast enough to avert the crunch that will come when the world's growing population and its need for resources overwhelms the capacity of the planet to provide, Ehrlich said.

In an effort to head off such a catastrophe, he has joined with hundreds of other ecologists, social scientists and scholars in the humanities to start the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere.

The goal of the project, called MAHB for short, is not just analyzing human behavior as the world sits poised on the edge of ecological catastrophe, but starting a global dialogue that will eventually involve decision makers and the general public in altering society's response to its global predicament.

"We are trying to recruit the social sciences and the humanities into an attempt to make academia relevant in the world and help change the course of society," Ehrlich said. "If you are tired of living in a world where leaders think debt ceilings are more important than climate disruption and the degrading of ecosystem services, then do something about it: Join the MAHB and get active."

-30-

|