Mark Mancall, Stanford history professor emeritus and founder of Structured Liberal Education, dies at 87

Mancall shaped the lives of generations of students through his research, teaching, mentorship and transformative commitment to undergraduate life and education.

Mark Mancall, professor of history, emeritus, in the School of Humanities and Sciences, died in his Stanford home Aug. 18. He was 87.

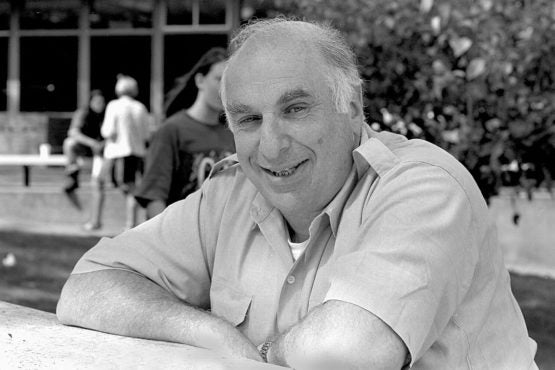

History Professor Mark Mancall advanced undergraduate education at Stanford by starting the Grove House residential learning project, establishing the Structured Liberal Education program and re-envisioning Overseas Studies. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A formidable presence at Stanford and in higher education, Mancall helped transform undergraduate learning by starting the Grove House residential learning project, establishing the vibrant residence-based learning academic program known as Structured Liberal Education (SLE) and re-envisioning the Overseas Studies program. Generations of students and colleagues remember Mancall not only for the breadth and depth of his fierce intellect but also for the spirit of generosity and compassion that animated everything he did.

“Over the half-century that I knew Mark, we sparred and partnered, laughed and argued, all in the context of our shared love for Stanford and especially for undergraduate education,” said David Kennedy, the Donald J. McLachlan Professor of History, Emeritus.

An expert on the history, religions, languages and cultures of Central and Southeast Asia, Mancall joined the faculty of the Department of History in 1965. He is the author, co-author or editor of six books, including Russia and China: Their Diplomatic Relations to 1728 and China at the Center: Three Hundred Years of Foreign Policy. He taught courses in Chinese history, Buddhist social and political theory, South Asian history, the history of socialism and Marxism, and Israeli history.

“Mark had a real and profound impact on my time at Stanford. He was the perfect blend of hard and gentle, challenging and supportive,” said Chelsea Clinton, BA ’01, who majored in history and served as a writing tutor for Structured Liberal Education. “He was also the most charming, lovely and loving curmudgeon I ever met. I could not imagine my time at Stanford without him and am so grateful for his mentorship in the classroom and in life.”

Revolutionizing undergraduate education

Mancall’s dedication to undergraduate education and livelihood was evident immediately after he joined the Farm. In his early days at Stanford, he played an important role in trying to temper student unrest of the late 1960s and guide it toward nonviolent, constructive directions. Upon learning of an empty fraternity house, Mancall helped establish the groundbreaking Grove House, the first co-ed residence on campus – and one of the first in the United States. Considered a daring venture at the time, Grove also hosted in-house seminars, a testament to Mancall’s aspiration of building communities that blended academic and residential life.

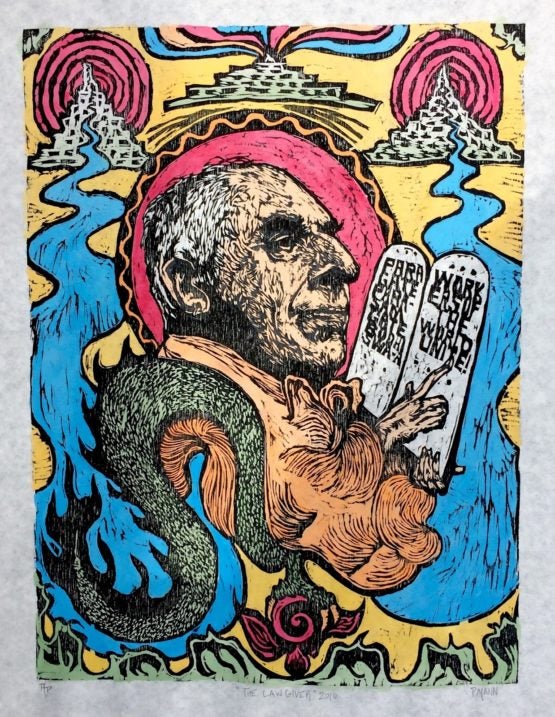

Woodcut portrait created by former SLE lecturer Peter Mann, PhD ’12, upon Mark Mancall’s retirement. (Image credit: Peter Mann)

“Moving into Grove House as it opened midway through my freshman year transformed my Stanford experience,” said Philip Taubman, BA ’70, who is an affiliate at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation after a career at the New York Times. “Grove opened new intellectual vistas, put me in touch with faculty from across the university and other colleges nationwide who came to dinner, and gave me an exhilarating sense that longstanding conventions of campus life could be changed. Mark’s leadership of Grove made it all possible.”

Mancall’s pioneering of residential education at Grove, where he served as director until 1971, became a precursor for Structured Liberal Education (SLE), which he established in 1973. Designed to serve as a tight-knit liberal arts college experience within the larger university, SLE is an integrated program that combines the reading of foundational texts with writing instruction for about 90 frosh each year who live together in East Florence Moore Hall.

“I wanted to take … a group of students and educate them … according to a classic answer to the question of, ‘What is it important to know? What is it important to understand? What are the sine qua non of an educated human being?’” said Mancall in an oral history interview with the Stanford Historical Society.

Mancall’s vision grew into a beloved gem on campus, a thriving intellectual and social community that shaped the lives of thousands of students.

“It’s hard to exaggerate Mark’s importance in creating and maintaining a central space for a freshman-year broad liberal education at this university,” said Debra Satz, the Vernon R. and Lysbeth Warren Anderson Dean of the School of Humanities and Sciences. “A force of nature, he engaged students and colleagues on topics from Marxism to Bhutanese Buddhism and encouraged students to brush away platitudes and received answers and chart their own paths, informed by engagement with ideas that matter. Mark’s legacy will live on in the many lives that were changed by their engagement with his challenging teaching and erudition.”

In addition to directing SLE from 1973 to 2008, Mancall was one of the program’s discussion section leaders for decades and was infamous for pushing students to dig deep in the search for knowledge and understanding.

“Mark challenged me to stretch beyond what I thought myself capable of doing, to think beyond the blinders I had imposed on my own imagination and be bold and creative in how I envisioned my role in the world and how I could best use my talents to serve others,” said SLE alumna Viria Vichit-Vadakan, BA ’11, who considers Mancall both a mentor and a dear friend.

While Mancall was first establishing SLE, he was also helping shape and grow Stanford’s education opportunities abroad. From 1973 to 1985, he served as the director of Stanford’s Overseas Studies Program. Under his leadership, two of Stanford’s overseas studies locations changed: in England it moved from Clivedon to Oxford, and in Germany from Beutelsbach to Berlin. He also developed the France program, which was located in Tours, to include Paris homestays.

Mancall advocated for each location’s curriculum to be developed based upon the reality of the country in which they were located to make the best use of their respective intellectual and historical resources. He helped begin the shift from a traditional to a more expansive presence, establishing (now closed) programs in Haifa, Israel, and Krakow, Poland. In his oral history interview, he emphasized how essential it was, and is, to prepare students to be transnational citizens who are “able to move in the world with understanding and humility.”

Whether teaching in FloMo dorm or in Florence, Italy, serving as an administrator or a mentor, Mancall made an indelible impression on students up until his passing. “Mark changed my life. He was an extraordinary teacher and friend. My studies with him taught me how to see,” said Anat Peled, BA ’20, who is now a Rhodes Scholar.

A transnational citizen

Mancall was born in New York City and raised in Los Angeles. He received his bachelor’s degree in Far Eastern languages from the University of California, Los Angeles. He then went on to Harvard University, where he earned his master’s degree in East Asian regional studies and his doctorate in history and Far Eastern languages.

During his graduate program, he studied and lived for a year each in Finland, Taiwan, the Soviet Union and Japan, which he called a profoundly formative experience. While at Stanford, he led numerous travel study journeys to China, India, Nepal, Central Asia, Indonesia, Tibet and Bhutan and held visiting professorships at El Colegio de México and the University of Haifa, Israel.

As a scholar with a lifelong fascination with places where ethnic identity and political identity intersect, Mancall decided to take a sabbatical year to Bhutan in the mid-1990s. Bhutan became a central part of his life and activism thenceforth, and, in turn, Mancall became a part of Bhutan’s history.

He became an advisor to the royal family as well as an advisor to the individuals constructing the Bhutanese constitution. From 2008 to 2011, he served as president of the Bhutan Centre for Media Democracy and director of Bhutan’s Royal Education Council. In 2004, he was given the rare honor of Bhutanese citizenship. Mancall also adopted Dechen Wangdi, who was one of his first drivers in Bhutan; Dechen and his wife and children eventually joined Mancall in his home on the Stanford campus.

“I don’t think I ever understood what it meant to change someone’s life until I met Mark,” said Vichit-Vadakan, who spent time with Mancall in Bhutan helping to transform the country’s education system. “Every time I spoke with him, I felt seen and heard as a whole person and never anything less than my fullest, most alive self.”

“‘Peace and freedom,’ he would always say at the end of every transformational conversation. ‘Peace and freedom to us all,’” Vichit-Vadakan said. “Mark lived his life as one unbroken and relentless offering of himself to the world, and I can only hope to honor his memory by striving to continue this immense legacy of service.”

Mancall is survived by his son, Dechen Wangdi (Tashi), and three grandsons, Kinley, Garab and Tobden.

Listen to Mark Mancall’s oral history as recorded by the Stanford Historical Society and A Shareable World, a podcast that featured conversations between Mancall, under the pseudonym “Big Mike,” with SLE lecturer Greg Watkins, BA ’85, PhD ’03.